It is a winter morning in 1946. An Austin A40 stops in front of a typical middle class street house in Mysore, tile-roofed in the old architectural style that gives you a clear view, if you stand outside the front door of the backyard, your eyes sweeping past the three or four living areas of the residence — an authentic agraharam dwelling. Two young men, smartly dressed in white kurta pyjamas, each carrying a musical instrument, get down and stretch their arms and legs, before heading towards the front door. The young man seated in the front verandah jumps up startled out of his newspaper-reading reverie. Inside, doing his daily sadhakam in the morning, is his grandfather Mysore Vasudevacharya, one of the elder statesmen of Carnatic music, a composer par excellence. Young Krishnamurti’s jaw drops in shock and delight as the third man in the car introduces the other two visitors as Ravi Shankar and Allah Rakha, already rising stars in the firmament of Hindustani music, fresh from a concert in the city the previous evening. The mouth remains open for the rest of the morning as the sitar and tabla maestros not only show the greatest reverence for the senior artist but sit down before him to play a mellow morning raga after he expresses his regret that he had not known of their concert.

The visit to the Vasudevacharya home was no surprise. Pandit Ravi Shankar had much love and respect for things and people south Indian — the ragas, rhythmic sophistication and rigour of Carnatic music, the great artists from Tiger Varadachariar and Veenai Dhanammal to M S Subbulakshmi and T Balasaraswati, even the young musicians he listened to regularly in the last two decades of his life when they performed at San Diego, his adopted California home.

True, he was a matinee idol among classical musicians, and perhaps because of his vulnerable looks and charisma, taken less seriously in his own country as the practitioner of a traditional art than he yearned to be, but he was wedded to his art. Few of India’s music greats had to handle as much adverse criticism as Ravi Shankar had to endure in a lifetime of endeavour to project the greatness of Indian music to the world. For long accused of diluting Indian classical music to please Western audiences, the maestro was deeply hurt by such charges. Yet there was no denying the purity of the sound produced by his sitar, his brilliance as a composer and creator of ragas, his unparalleled eclecticism that took some of the finest ideas and attributes of south Indian classical music to its north Indian counterpart.

Because of his vulnerable looks and charisma, he was taken less seriously in his own country as the practitioner of a traditional art than he yearned to be.

Born in Varanasi on April 7, 1920 as the youngest of four brothers, Ravindra, named after Nobel laureate Tagore, hailed from a privileged background. His father, a bar-at-law, and a minister in princely states, was an amateur singer at local soirees, and there was plenty of music and dance in the family. Elder brother Uday Shankar was to become a world famous dancer, taking his troupe, including his siblings, all over the West. Another brother Rajendra was involved in theatre, and stored his drama troupe’s musical instruments at home. Ravi would play those in secrecy.

Young Ravi survived the trauma of his father abandoning his family, and his mother raising her sons on slender means — to experience happier times when brother Uday Shankar became a sensation in the West with his Indian dance troupe. Going at age nine to Paris, where he saw “too much, too soon,” and amidst hectic performance tours and revels with the glitterati, Ravi became an acclaimed dancer in his brother’s Indian ballets. He was still shy at twenty when he turned his back on stardom to answer the call of the sitar, going from a life of comfort to rural Maihar and gruelling lessons from the great Baba Alauddin Khan. He did riyaz for 14 hours a day! Hindustani vocalist Lakshmi Shankar, Ravi’s brother Rajendra’s wife — taught and mentored in music by Ravi when illness forced her to quit Bharatanatyam — once said, “I’ve seen blood coming out of his fingers.”

Ravi Shankar explained the reason behind his drastic step. “When I was a child, my mother called me chanchal, restless, my guru called me a butterfly. I’ve tried to harness that restlessness in my search for the highest experience of shanta. Listeners found my music meditative, blissful, even healing. Maybe an artist has to go through hell to create heaven for others.”

Ravi Shankar married Annapurna Devi, Allauddin Khan’s daughter and gifted exponent of the surbahar, a string instrument akin to the sitar. Surrounded by murmurs about Ravi Shankar’s alleged resentment of his wife’s superior talent, the marriage did not last very long. Annapurna Devi retired from concert music and led the life of a recluse until her death in October 2018.

Listeners found my music meditative and blissful. Maybe an artist has to go through hell to create heaven for others.

– Pandit Ravi Shankar

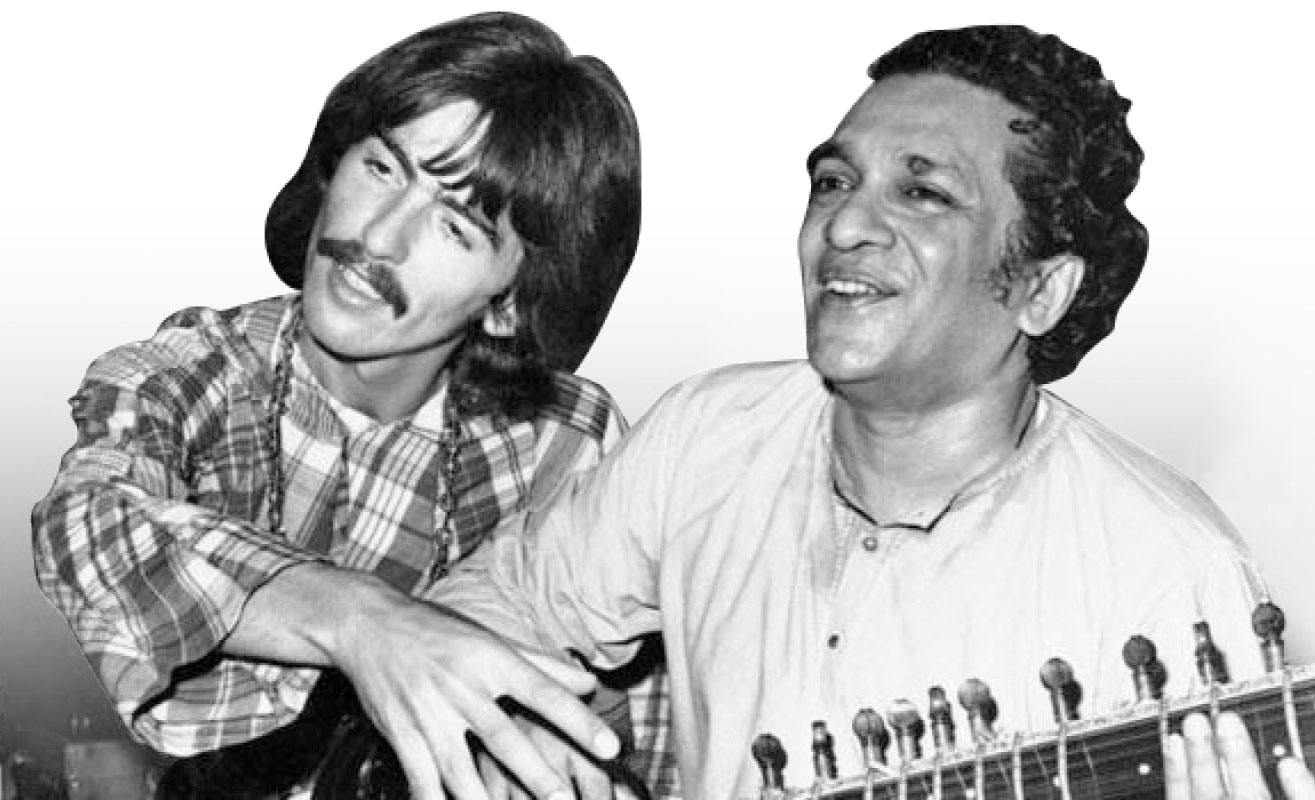

When he went West again as a sitarist in the 1950s, the audiences were small and unappreciative of Indian music. He gave it to them initially in small doses, educating them step by small step. Through countless lecdems at university campuses, he won them over with his natural charm and articulation. He put Indian music on the world map with his own concerts as well as collaborative efforts with some of the leading lights of Western music. Friend and collaborator Yehudi Menuhin, the renowned classical violinist confessed, “I was terrified to play with Ravi. I felt I was in no way worthy.” The likes of flautist Jean Paul Ramphal, conductor Andre Previn and composer Philip Glass felt they were privileged to work on original music the maestro composed. Beatle George Harrison took sitar lessons from him, made albums and toured with him, and edited and introduced his autobiography.

The maestro approached his mission of propagating Indian classical music with utmost seriousness. An episode during a 1950s tour of Brazil illustrates this.

Beatle George Harrison took sitar lessons from Ravi Shankar, made albums and toured with him, and edited and introduced his autobiography.

Returning to their hotel from a concert, his troupe, which included tabla wizard Allah Rakha, were confronted by a power outage. They had to climb the stairs to their 14th floor room carrying sitar, tanpura, tabla and other paraphernalia. Ravi Shankar walked briskly up with the others trudging along far behind, moaning and groaning. On the tenth floor, a couple of them sat down, unable to walk any further. Ravi Shankar made three or four trips up and down from then on, carrying the whole load solo, and finally ferried his exhausted colleagues to their room! He said to them, “Don’t you realise what a great thing we’ve done? We are in Rio de Janeiro, exhibiting our music to the Brazilians and making them love it. It’s no small feat. All our troubles are minor. We’re taking our music to every nook and corner of the world, and that’s all that matters.”

A stout defender of Ravi Shankar’s classicism, Lakshmi Shankar once said, “His Beenkar gharana came from the dhrupad style. It is not light, contrary to all the criticism levelled against his music. Even when he plays a thumri or a gat, he is strictly classical. He admitted making some format changes to attract Western audiences to our music. If he had not done that, it could have meant curtains for our music in the West.”

I was terrified to play with Ravi. I felt I was in no way worthy.

– Yehudi Menuhin, renowned classical violinist

Over decades of tireless travel and varied performances, Ravi Shankar became one of India’s most celebrated musicians. Awarded the Bharat Ratna in 1999, he received some 15 honorary doctorates, the Ramon Magsayasay Award, two Grammys, the Crystal Award from Davos, the Fukuoka Grand Prize Award from Japan, and countless other awards and honours. He played his music to a great variety of audiences, from the knowledgeable audiences of Varanasi and Pune, to wildly cheering young fans at the Woodstock and Monterey Pop music festivals. He orchestrated Indian music for All India Radio, composed music for Indian and international ballets and films including Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali, Godaan, Anuradha, Gulzar’s Meera and Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi, and with Ali Akbar Khan, kickstarted a whole new variety of Indian classical music — the jugalbandi.

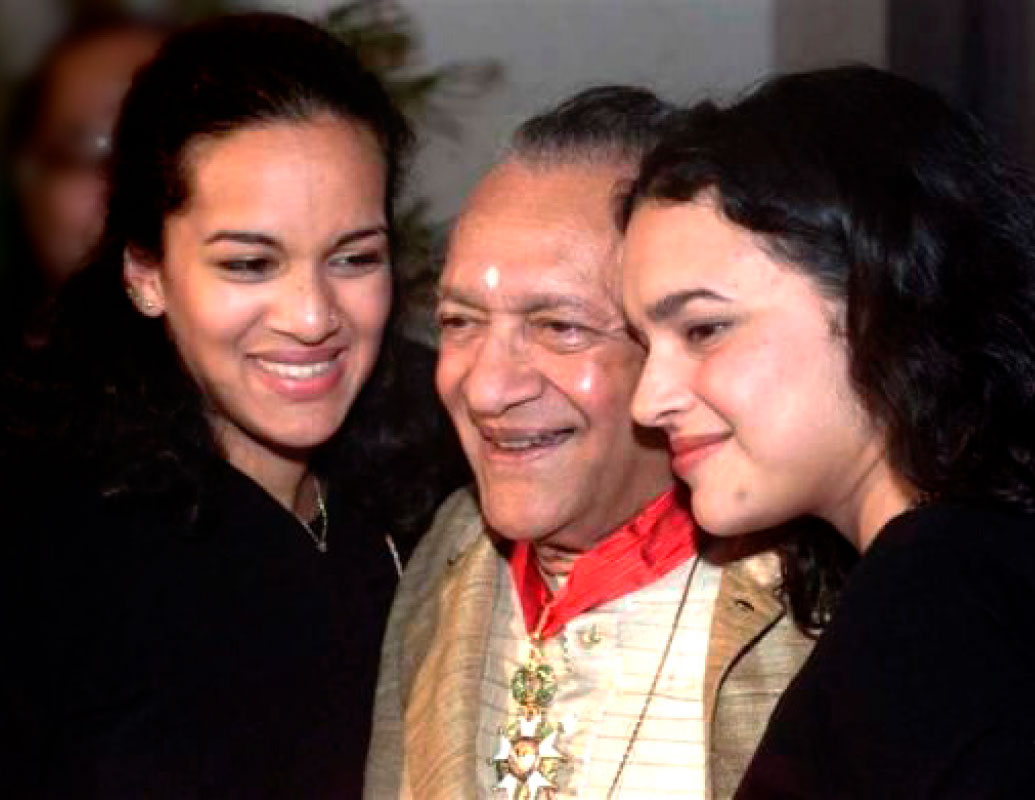

He was a devoted guru who nurtured young musicians with loving care no matter where they came from. Daughter Anoushka from his second marriage was only one of them, though he was sometimes accused of promoting her. His iconic gurukula ‘Hemangana’, built in Varanasi in 1973–74, housed RIMPA, the Ravi Shankar Institute of Music and Performing Arts. There, 20 to 25 students from all over India annually learnt from Ravi Shankar who taught them through many media — including games he devised for their evening entertainment. In the morning, he was a hard taskmaster, a perfectionist. “Is this the man who laughed and joked with us last night?” the students would wonder. At an annual festival at Hemangana, eminent musicians and dancers performed, with Ravi Shankar’s concert providing the finale.

The atmosphere of Hemangana was fabulous with its aesthetically designed arches, student quarters, and its beautiful orchards. “I’ve never experienced anything so Indian,” a visiting Satyajit Ray once said. Hemangana could not however be sustained beyond three years, because the restless spirit that he was, Ravi Shankar had to move on.

When he passed away at age 92, there had been unresolved questions over his father’s mysterious death, early sexual abuse, his troubled relationship with son Shubhendra who died young, but Ravi Shankar had come to terms with the ebb and flow of his long and dramatic journey on earth. With the strong support of his wife and anchor Sukanya and the joy that spotting young talent had brought him through his many group productions in the twilight of his life, he had achieved peace.

The writer is an author and former editor of Sruti magazine.