Geet Gaya Pathharon Ne.’ This lovely song from the 1960s Hindi film of the same name had me wrong-guessing the identity of its singer. Was it Asha Bhosle or Geeta Dutt, I wondered. I could not make up my mind, for the voice sounded slightly different from these two delightful representatives of film music capable of handling the nuances of raga music. I wasn’t even sure that Geeta Dutt was still alive. Was it Lata Mangeshkar, the reigning queen of film music? I could not google the answer, for that small wonder of the Internet was still decades into the future then. I did the only thing to do: I sat next to the radio listening to Vividh Bharati waiting for the song to be played again. I did not have to wait for too long. Within a week, I had the answer: Kishori Amonkar. I had never heard the name, but I was impressed. What a brilliant new playback singing voice!

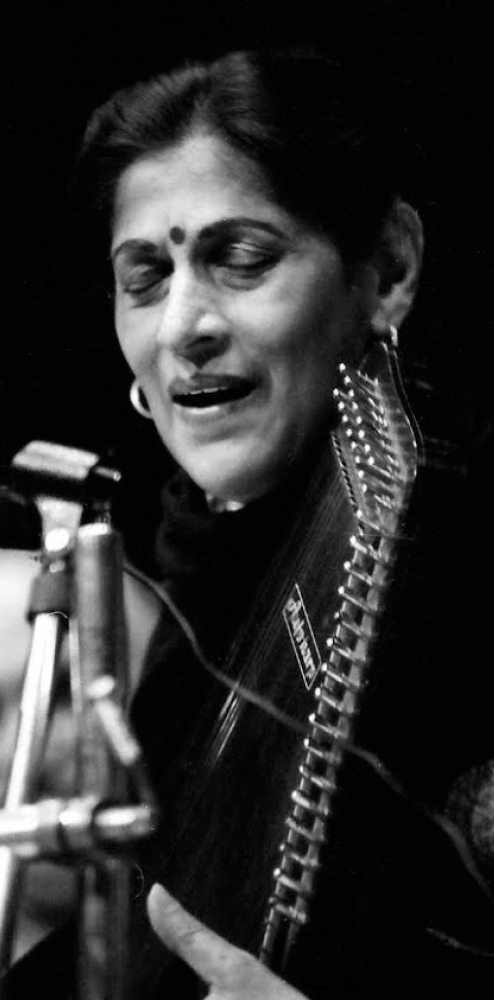

It took me a couple of years to realise that this was not a regular contributor to film music, that Kishori Amonkar’s was an enviable classical music lineage, that she was the talented daughter of the formidable grand dame of the Jaipur-Atrauli gharana, Mogubai Kurdikar, who was also her first guru. I was to learn from available literature, notably the writings of Mohan Nadkarni and Deepak Raja, that she was one of the leaders of the avant garde movement within her gharana. According to Raja, “Kishori was not only a formidable musician, but also the chief ideologue of the romanticist movement — by the power of her intellect, erudition, and excellent articulation in at least three languages, including English. She was, incidentally, known to possess one of the finest private libraries on musicology and aesthetics. She held audiences spellbound at seminars and conferences, as much as she did on the concert platform.” Raja went on to describe her as a romanticist, whose interpretations of ragas gave them a spice hitherto unattempted in her orthodoxly cerebral school.

For borrowing from other gharanas, Kishori was deemed a rebel, a charge she dismissed, even denouncing the gharana system as artificial and stifling of creativity.

Kishori’s dalliance with cinema music was no more than a mild flirtation. Her mother certainly prevented it from blooming into a full-blown affair, by threatening her with the dire consequence of being denied a final look at her physical remains when the time came, should she continue to pursue her tinsel dream.

The next Kishori Amonkar song to captivate me was the bandish Sahela re in the raga Bhup or Bhupali, one of her favourite ragas, along with Bageshri. This song in Kishori’s voice has captivated generations of listeners. Hers is a beautiful interpretation, sentimental, sensuous almost, very different from the clinical treatment the raga received in her gharana. For this deviation from the norm, and for borrowing from other gharanas, Kishori was deemed a rebel, a charge she dismissed, even denouncing the gharana system as artificial and stifling of creativity. She believed the musician should be totally free to pursue the beauty of raga music unhindered by any restrictions other than the grammatical boundaries of the raga.

Listening to Kishori Amonkar, one was immediately struck by a sense of deep loneliness rendered rich and luminous, bearable and ennobled by the music.

Though I love Sahela re by Kishori for its delicately feminine appeal — described by some as the artist’s foray into a romantic interpretation of the raga, my favourite renderings in that mode across genres primarily include the exciting explorations I grew up enjoying from great Carnatic vocalists like Maharajapuram Viswanatha Iyer and M L Vasanthakumari and the incomparable Lata Mangeshkar’s Jyoti Kalash Chhalke from the movie Bhabhi ki Chudiyan in the 1950s. In recent years, I have found the multifaceted Sriram Parasuram’s portrayal of the raga (both Bhup and Mohanam, its southern parallel) both evocative and pure of enunciation — in voice as well as on violin strings.

As she evolved as a musician, Kishori became more and more convinced that music must have emotion at its core, that to truly find a raga in its true colours was to plumb its emotional depths, that without that emotional quotient, music stayed at a mundane level of technical mastery at best. To her the musical notes had distinct personalities, were in fact persons that spoke to her, sang to her.

She held audiences spellbound at seminars and conferences, as much as she did on the concert platform.

Anyone who has listened to Kishori Amonkar regularly and witnessed her on-stage demeanour will agree with Raja. The loneliness was palpable. Hours before the concert, she started preparing to focus totally on merging with the music, with the ragas she started practising weeks ahead of the programme, so that she could move into a trance once she started singing. The trance was all important to her, the reason why she allowed nobody to enter her green room, the reason why she made no secret of her annoyance when people in the audience including senior artists moved around or greeted one another. “How can I go into a trance if they do that?” she would ask. Sadhana was sacred to her; it was never mere practice. It was an act of complete devotion to the music. She likewise made a clear distinction between a guru and a teacher. The guru showed you a path, and left you to explore it on your own.

Achieving a state of total self-forgetfulness on stage was not always easy. Kishori often took a long time to warm up in a concert. As a result, her music could seem desultory and listless while she was struggling for that complete merger with the sur, the precise arrival at the perfect shadja or rishabha or nishada. Audiences, even diehard fans, could grow impatient while this lonely perfectionist went in search of musical nirvana — and getting lost in byways and allies. When she did hit that pluperfect note, it was sheer bliss. Who could complain after that?

“I suppose it takes a genius to acknowledge another,” she said with a shy smile, upon learning that Zakir Hussain described her so.

To quote Deepak Raja once again, “Listening to Kishori Amonkar, one was immediately struck by a sense of deep loneliness… a loneliness rendered rich and luminous, bearable and ennobled by the music. It gathered the listener in with its beauty and left one longing for more.”

This loneliness, plus the deep pain and anguish she suffered as a girl growing up, whenever she witnessed the humiliating treatment her mother was meted out during her performance career, must have led to Kishori’s temper tantrums and idiosyncratic behaviour once she established herself and reached diva status. She could drive organisers round the bend with her sometimes extravagant, eccentric demands — as when she insisted on a white Mercedes Benz and a luxury suite with white walls in a five-star hotel, when on a concert visit to Bengaluru — or the inordinate time she took over aligning her tanpuras and completing sound checks before the start of her performances. The wait was more often than not totally worth it, as she fulfilled the immense promise of a genuine Kishori Amonkar concert.

Personally, for all her indisputable mastery of her art and the depth of her musicianship, I found her voice rather high-pitched, and therefore preferred the more full-bodied voices of Prabha Atre, or Veena Sahasrabudhe, not to mention the near-masculine tones of Gangubai Hangal or such magnificent voices of the Carnatic music stream as M S Subbulakshmi, D K Pattammal, M L Vasanthakumari or T Brinda. This view of mine would of course be considered blasphemous by both her thousands of fans and the more serious followers of classical music of vastly superior scholarship.

Kishori Amonkar, who left us four years ago, and received every conceivable honour including that of Padma Vibhushan, professed an elaborate disdain for awards and prizes. “I don’t need the Bharat Ratna,” she is said to have told an admirer who rued what he considered a lapse on the part of the nation in failing to bestow on her that crowning accolade. Recognition by artists she respected was quite another matter. “I suppose it takes a genius to acknowledge another,” she said with a shy smile, upon learning that Zakir Hussain described her so. “I love him,”she added. The diva was a romanticist indeed!