The summer that the Indian men’s cricket team recorded a memorable home series win against the Australians, my 11-year-old came down with chickenpox. Predictably, I followed suit, and as we were the only two in the house and life had to move on, my aunt moved in to give us a hand.

By then, the first four books in the Harry Potter series had been published and were proud inhabitants of our home too — a little worse for wear from being passed on from hand to grubby hand, but much-loved. So, when he discovered his dear Sumana aji ensconced bag and baggage at home, my son’s first question to her was, “Have you read Harry Potter?”

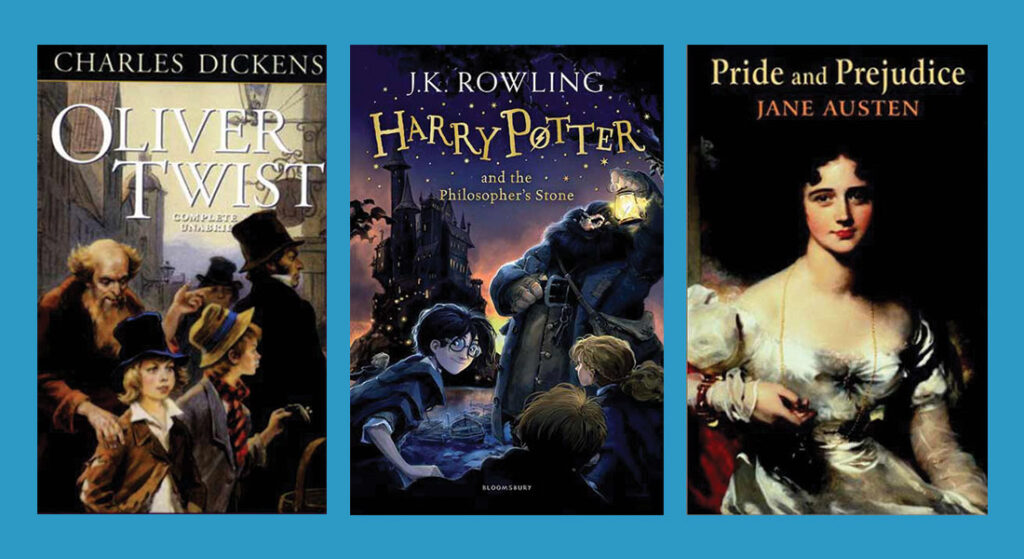

When she said no — to be honest, she didn’t know who in the wide world he was — he promptly thrust his well-thumbed copy of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone into her hands and said: “Read.” My aunt laughed and said, “Ok.” She had no intention of doing so, but she had not contended with her grand-nephew’s agenda. Every evening, without fail, he cross-examined her on the finer details of Philosopher’s Stone, checking exactly how many pages she had read, relentlessly quizzing until she was shamed/cajoled into ploughing through the pages. By the time her nursing duties ended, she had just about managed to breast the tape.

I have no doubt that many of you have similar or other stories to relate about books and reading and mad readers. For instance, I thank the universe every day for the many brilliant writers and the wealth of amazing titles and for a love of reading. Honestly, I don’t know what I’d have done had there been no books.

Do you feel that way too? Depressed even contemplating a time when there were no books to read? No libraries, no bookshops, no secondhand treasure troves, no Higginbothams and book birds?

Growing up in a small town in West Bengal, my friends and I each contributed our own precious stock to build a library and charged a few paise for every book borrowed. This was before we knew anything about anything, least of all the economics of income, expenditure and investment. But we knew we wanted more books and the best way to do that without adult intervention was to raise our own capital. An Enid Blyton, back in the 1960s, cost about Rs 2.50. So that was our goal, as many times Rs 2.50 as possible. The only way that would happen was if we got all our friends and their friends to borrow books from our library. And so we wolfed down Richmal Crompton, Elinor Brent Dyer, Susan Coolidge, Angela Brazil, WE Johns, Louisa May Alcott, LM Montgomery and anything else we could lay our hands on, including the Illustrated Classics and Phantom and Mandrake. Logic, not awareness, guided us through acquisitions, marketing, campaigning, and we ran the library from a comfortable space in the home of a (I now realise) generous and encouraging ‘uncle’ who lived in our colony.

Later, in our teens, it was local lending libraries — the Ramonas and Ravirajs — that fed an unquenchable thirst. My friends and I ran through Louis L’Amour, Zane Grey, Edgar Wallace, Perry Mason, Agatha Christie, Taylor Caldwell, Georgette Heyer, Ayn Rand, Allen Drury, Barbara Cartland, Richard Gordon, Alex Hailey, Leon Uris, Irving Stone… and of course the ubiquitous Mills&Boons, getting ‘hotter’ as the years rolled by!

The British Council library and the library at the USIS also went into the mix, throwing up Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, Vladimir Nabokov, Doris Lessing, Somerset Maugham, Ernest Hemingway, Dostoyevsky, Truman Capote, F Scott, Fitzgerald, Leo Tolstoy, Albert Camus, apart from the air-conditioning and occasional big print editions for grandfathers and grandmothers. We read and read and read our holidays bare; we lost ourselves in new and exciting worlds. We flew on words. We journeyed on the winding roads of imagination. We lost track of time. We met Raja Rao and RK Narayan, Kamala Markandeya and Anita Desai, Nayantara Sahgal and Prem Chand, and read from the Ramayana and Mahabharata, apart from stories from the Bible popularised in freely available, colourfully printed pamphlets.

But the best mythological tales were those my grandmother spun, any time of day or night, gathered from infinite sources. They came with sound and fury, coloured by blood and gore, twisting and turning in uncanny ways, leaving my cousins and I thirsting for more. She never tired; she cooked up the most delicious meals and sometimes served them up to us in little balls as we sat around her, while her eyes flashed and mouth spouted an endless, heartfelt stream of word-pictures. We sat goggle-eyed, mesmerised, swallowing every mouthful of fiction and fact without question. Stories do that.

A dear Swedish friend with an academic interest in religion and spirituality, was once discussing god and the ever after with her little daughter, then about 8 or 9. Suddenly the little one piped up, “I don’t believe in god. I believe in Astrid Lindgren.” Truly, the Swedish editor and writer Astrid Lindgren was a phenomenon, as many of you will remember. Most famous as the creator of the internationally beloved character, Pippi Longstrump (Longstocking), Astrid Lindgren has delighted readers across many generations with a compelling and eclectic range of stories. She’s been widely translated, and is loved all over the world; many still cannot excuse the Nobel committee for not awarding her a Nobel for literature. She was extraordinary.

In an article headlined ‘Astrid Lindgren spoke, people listened’, British journalist David Wiles wrote: “At the age of 68 she submitted an opinion piece to the Swedish daily Expressen on the subject of a loophole in the Swedish tax system, which meant that she, as a self-employed writer, had to pay 102 per cent tax on her income. Lindgren wrote the piece in the style of a fairytale, and it had an immediate impact. Pomperipossa in Monismania, published in 1976, became front-page news and led not only to a change in the tax law, but eventually to the fall of the social democratic government that had been in power for 44 years.”

Astrid Lindgren spoke up, she took on the system, she was sophisticated and had the last word.

Who knows how long it would have taken us to discover RK Narayan if writer Graham Greene had not encountered and fallen in love with Swami (Swami and Friends)? JK Rowling says she sent her first Harry Potter to 12 different publishers before Bloomsbury finally picked it up — and what a difference that made to the publisher’s profits! In an interview long ago, Nigel Newton, who was then chairman of Bloomsbury Publishing, revealed that it was his eight-year-old daughter, Alice, who pestered him for more Harry Potter after reading the first chapter of Rowling’s submission. Instead of reading the chapter himself, Newton had passed it on to Alice who was so enchanted she couldn’t wait to read what happened next. We know.

Swami and Friends was first published in 1935. It continues to be reprinted and read. Pippi Longstocking was first published in 1945. It continues to be reprinted and read all over the world. And Harry Potter made Bloomsbury, in a manner of speaking.

Truly, truth is more magical than fiction.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist.