I love the Swedish writer Astrid Lindgren. She wrote primarily for children, but for many years she worked as a books editor, and was also a fearless political commentator. An official Swedish website has an article by David Wiles headlined: “Astrid Lindgren spoke, people listened.”

Curiosity piqued, I scrolled the piece, and found this: “At the age of 68 she submitted an opinion piece to the Swedish daily Expressen on the subject of a loophole in the Swedish tax system, which meant that she, as a self-employed writer, had to pay 102 per cent tax on her income. Astrid wrote the piece in the style of a fairytale, and it had an immediate impact. ‘Pomperipossa in Monismania’, published in 1976, became front-page news and led not only to a change in the tax law, but eventually to the fall of the social democratic government that had been in power for 44 years.”

It appears that journalists would often ask her opinion on issues and print what she said. “Indeed,” Wiles writes, “she was so influential that on the issue of Sweden’s proposed membership of the EU — which she opposed — the pro-EU press made a point of not talking to her.” Sweden, as we know, is part of the EU.

I have many writer friends who get offended when they’re asked about the story behind the story. I don’t. Imagination doesn’t fall from the sky; you have to work with something.

– Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

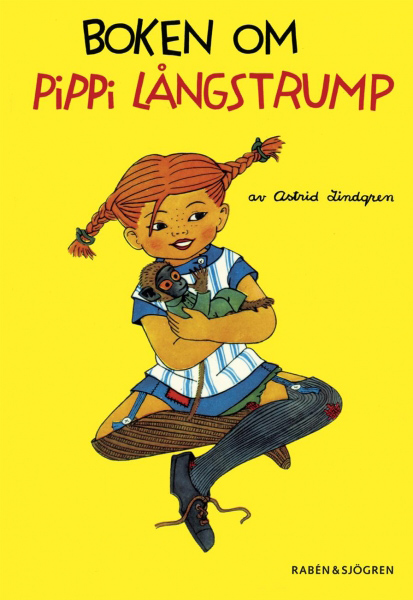

This was the same Astrid Lindgren who shot to fame with a book for children about a nine-year-old, freckle-faced, red-haired little girl called Pippi Longstrump. Translated into some 70 languages, including into Hindi as Pippi Lambemoze, when it was first published in the 1940s, the book so outraged ‘proper’ society that some people went to great lengths to have it proscribed. In recent times the third book in the series, Pippi in the South Seas, was pulled out of Swedish libraries apparently for its racist content. The interesting thing, though, is that the character, Pippi, was actually born in the imagination of Astrid’s daughter.

Karin was about 9 or 10, lying in bed sick and bored when she commanded her mother to “tell me a story about Pippi Longstrump”. The rest became history.

Equally dramatic is the story of author Amish Tripathi who shot to fame with the Shiva trilogy: a re-imagined mythology of Shiva as a human being. Many years ago, I committed the ultimate sacrilege of declaring to a bunch of 14/15-year-olds that I didn’t like the books (The Immortals of Meluha, The Secret of the Nagas, The Oath of the Vayuputras). Predictably, they were outraged. But for the fact that Indian teenagers (back then, at least) tend to be well behaved, I would have been lynched on many counts.

From all accounts, Amish Tripathi had put in place a terrific marketing strategy, thanks to the efforts of his wife, Preeti. At the launch of his first book, The Immortals of Meluha, Preeti suggested that bookstores offer customers free copies of the first chapter. This caught the readers’ fancy; naturally they bought the book, and within a week or so, it became a bestseller. Now, with many more books to his credit, Tripathi is assured both a loyal readership and the sale of his books in millions.

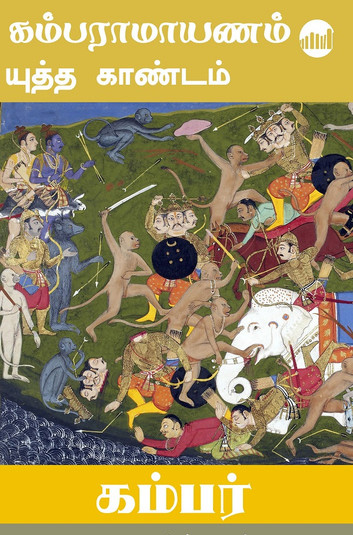

Okay, so these are modern times. How about ancient times? How about Ramayana-times, for instance? Dated around 500 BCE, Ramayana is attributed primarily to Valmiki who wrote the epic in Sanskrit. Valmiki’s Ramayana is popularly regarded as the ‘original’. However, there are records of some 300 versions of Ramayana: in Tamil by Kambar, called Kamba Ramayana; Ramcharitmanas by Tulsidas in Awadhi; Bhavartha Ramayana in Marathi by Eknath; Krittivasi Ramayana by Krittibas Ojha in Bengali, and so on. There are folk, tribal and classical versions, as also the Thai Ramakien, the Khmer Reamker, and the Lao Phra Lak Phra Lam, among others.

How Valmiki became Valmiki after having been born Ratnakar is a tale in itself. It appears he was a robber. One day, he was advised by a wise man to turn over a new leaf. Upon introspection, Ratnakar realised that the reason for his becoming a robber was to feed and fend for his family. So, following the meeting with the wise man, he said to his wife and children: Seeing as you are happy to live off what I get by robbing, can I assume that you would be willing to take on a share of my sins too?

His wife and children demurred and Ratnakar was shocked. As the truth sunk in he realised what he needed to do. He found himself a good spot and started to meditate on matters of a more profound nature. He went into a trance and became oblivious to the termites that began to construct an anthill around him. That’s how he earned the moniker Valmiki — from ‘valmik’ which in Sanskrit is the word for termite.

There, sitting on a divan, was Margaret Mitchell, and beside her was the biggest manuscript I had ever seen. The pile of sheets reached to her shoulders. She rose and said: ‘Here, take the thing before I change my mind’

– Macmillan Editor Harold S Latham

When the 1,037-page Gone With The Wind was first published in 1936, it cost all of a princessly three dollars. Accounting for annual inflation, internet resources and calculators suggest that its equivalent today would be about $54! Not exactly a cheap read! According to an article written by Edwin McDowell in the New York Times in 1981, at one time it seemed as though the book would not be published because the author herself had given up after working on it for three years. Macmillan editor Harold S Latham recalls a meeting in the lobby of his hotel in Atlanta in 1935: “…there, sitting on a divan, was Margaret Mitchell, and beside her was the biggest manuscript I had ever seen. The pile of sheets reached to her shoulders. She rose and said: ‘Here, take the thing before I change my mind.’ And guess what? Hidden among those pages was Pansy, not Scarlett O’Hara!

Why was Margaret Mitchell reluctant to show her manuscript? McDonnell says that “she said of her reluctance… ‘I just couldn’t believe that a Northern publisher would accept a novel about the war between the states from the Southern point of view’.”

Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in an interview to Salon once said, “I have many writer friends who get offended when they’re asked about the story behind the story. I don’t. Imagination doesn’t fall from the sky; you have to work with something. My fiction borrows from my life, but even more so from the lives of other people.”

Yes, stories behind stories are fascinating. Check out your favourite authors online and I promise you will be pleasantly surprised. Amitav Ghosh is among my favourite writers. Many people find his Ibis trilogy about the opium trade between India and China, and the East India Company, heavy going (Sea of Poppies, River of Smoke, Flood of Fire). I agree, it’s not easy, but the world he recreates and how he recreates it is amazing. This is what Jash Sen quoted him as saying in Scroll.in: “One of the greatest compliments I have ever received is from my friend and wonderful author, the late Sunil Gangopadhyay, who when releasing a novel of mine, said, “E to dekchhi bangla boi, shudhu ingrijite lekha! (But this is a Bengali book, only written in English!)”. It couldn’t have been said better.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist.