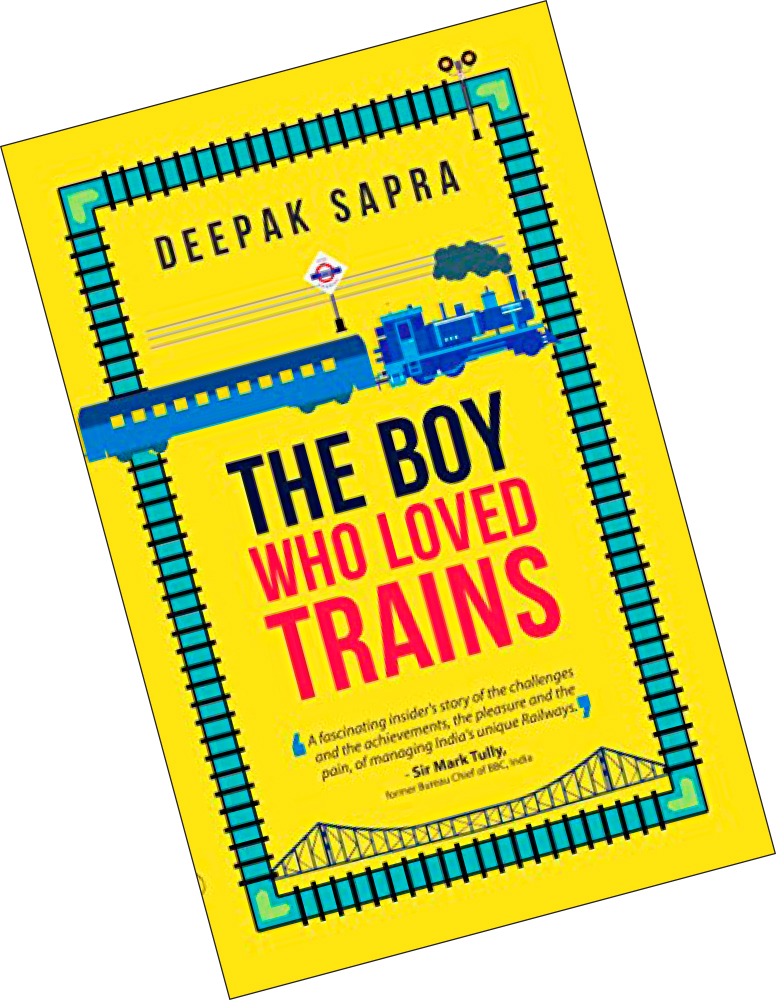

While mindless debates over national language, loudspeakers and uniforms distract and raise temperatures in an already overheated environment, the only sensible thing to do appears to be to soak in the fine thoughts of fine minds. In books, of course. Kavery Nambisan is known for her solid works of fiction (some, as Kavery Bhatt). Egged on by her publisher, she recently released her first nonfiction work, A Luxury Called Health, in which she draws upon her vast experience as a doctor to tell the story of medicine and medical practice in India, no holds barred. Deepak Sapra, the blurb tells us, was an officer in the Indian Railway Service who now writes on places and people. In The Boy Who Loved Trains, he tells an insider’s story of Indian Railways, no holds barred.

The title of Kavery Nambisan’s book resonates, the tagline intrigues: ‘a doctor’s journey through the art, the science and the trickery of medicine’. Less than halfway through the book which is part memoir and part rumination on the philosophy of medicine and the practice of healthcare based both on personal experience and academic research, up pops this paragraph: ‘Caring is as old as human existence. The single most comforting sensation is that of touch — an inbuilt force of survival. The prehensile hand, the sensorial palm and the exquisitely designed digits enhance the emotional impact of touch. The crow furls its wings over the just hatched fledgling; the mongrel licks away pain when her willful pup snags a paw on a barbed wire; a mother-elephant soothes with her trunk. Humans are capable of helping any suffering being, even when not bound by love or loyalty. This ability to empathize sets us apart as a species. The other trait that is exclusively ours is hate. We’ll stick with empathy.’

This one paragraph sums up the entire book in which the author’s voice shines through, sometimes uncertain, sometimes unequivocal, but always observing, reflecting, analysing, empathising. She makes you see: hospitals and humans working in hospitals, systems in and out of place, in swanky cities, in small towns, in the guns-dominated streets of Bihar, in a UK hospital and a small clinic in Kodagu… About every place and person, Kavery Nambisan writes fearlessly and with clarity, in prose that makes reading the book an unputdownable experience. We read about teaching and learning, the agony of decision-making, professional and personal loss, reaching the unreached, overkilling with treatments. Sometimes the simplest solutions are the best, she argues, even as she sets out a practical approach to the current pandemic.

All we know as passengers is that an accident has taken place, so many dead and wounded, we assign blame, but rarely do we know about, what’s happening behind the news coverage.

Deepak Sapra’s journey is different, but here too, it’s the people who stand out. As the author in the persona of Jeet Arora shares his love of trains with the reader, you tag along with him at the Indian Railways Institute of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering (IRIMEE) in Jamalpur, Bihar. You puff up your chest like the trainees as they are treated like sahibs by their attendants, whether it is a meal being laid out for them at a table on the station platform or being updated on the latest situation. For me, it was serendipitous that Arora was attached to Eastern Railway because names like Durgapur, Raniganj, Asansol, Coalfield Express recalled my own childhood in Bihar and Bengal.

But the journey is not all and always rosy, and there are many lessons in store for a young railway officer. Luckily, our Arora is a good learner. To offer an example: as he and the Carriage and Wagon Foreman, Karim, rush to the site of derailment of the Shatabdi Express near Durgapur, Arora wonders at the latter’s composure; he himself is quaking with fear. Karim then tells him about his experience at Bhopal station on the night of the gas leak from the Union Carbide plant on December 3, 1984: ‘I can still visualize Dastagir sahib, the station master on duty, running up and down the platform, asking the driver of the Bombay-Gorakhpur Express to start his train and move it out of Bhopal, even though it was 30 minutes before its scheduled departure. … it was a decision which perhaps saved thousands of lives.’ And although Dastagir collapsed after the effort, ‘…perhaps out of sheer will power, he regained his composure to run back to his office. He sent across messages to stop all train traffic coming into Bhopal, from all directions.’ At the station, people were collapsing like flies. ‘I was lucky to survive,’ Karim tells Arora. That one night removed all faintness from his heart.

Karim’s words give Arora courage and when they arrive at the derailment site they find that the Sr DME of Danapur Division, Nandan Kumar, who had been travelling on the train, has taken charge and is organising rescue efforts. Again, Arora is inspired by what he sees: ‘He…painstakingly went through articles of the individuals who had succumbed to get contact details for identification and arranged to keep their luggage safe in a makeshift tent which was put up. One by one, person by person, bag by bag, suitcase by suitcase, he went about this job for the next 48 hours — without sleeping for a moment…surviving on cups of tea that the team provided. When the relative arrived, he consoled and empathized with them.’ All we know as passengers is that an accident has taken place, so many dead and wounded, we assign blame, but rarely do we know about, let alone see, what’s happening behind the news coverage. Of course, Arora displays courage of another kind, the foolhardy kind, to jump on to a running train as it chugs past the platform at a particular station just to catch a few moments with his lady love; he jumps off it as it exits the other sloping end!

Humans are capable of helping any suffering being, even when not bound by love or loyalty

The romance of trains quite naturally tickled taste for more romance reading. Besides, what better escape from the grimness of a messed-up economy, a still-raging pandemic, growing unemployment, the polarisation of society, and the blanket of resentment, hate and insecurity that’s been thrown over India. In an earlier column, I had written about the first book of Sonali Dev’s trilogy about a migrant family settled in California. This time, upon my friend’s recommendation — never mind the second, read the third — I ordered Incense and Sensibility which spotlights the story of Yash Raje who is running for governor of California. Apparently, the title was suggested by Sonali Dev’s 13-year-old when she gave him a gist of the story and mentioned that Yash’s love interest was a yoga instructor called India. Her son knew only too well what a Jane Austen fan his mother was!

I said it before and I’ll say it again, one of the most interesting things about Sonali Dev’s novels is her multicultural approach. In Incense and Sensibility, India is one of three children adopted by their mother. She is from Thailand, sister China is from Nigeria, and brother Siddharth is from India (we don’t meet him in the flesh though, maybe there will be a novel about him…). Besides, all three have had cleft palate surgeries, but this information is by the way. The point is made, though. It’s soppy but fun.

Now, I have a new stash that includes…. But no, wait for it! Meanwhile, stay physically, mentally and emotionally cool. Live and let live.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist