It happened some 80 years ago in the times of Maharaja Bhupendra Singh of Patiala on a hot summer day. The inimitable Maharaja was holding interviews in a secluded part of the palace. A number of European candidates seeking posts in the Patiala State were standing under the sun. They had not been provided with chairs and were exposed to the scorching heat since it was impossible for anyone to sit on a chair when the Maharaja was in that part of the palace to hold interviews.

This scene from the well of memory came alive when I chanced upon a sheaf of yellowing sheets with notes recorded by D P Bhandari, Masters from Cambridge, a maternal uncle who served Patiala State as Development and Constitution Secretary and, among the Secretaries, was placed at first position. The old papers with fading letters ticked from a vintage typewriter recount some interesting anecdotes about Patiala and its rulers.

When Bhandari was called in for the interview after a short wait of half an hour, he recalls that the large room in which the Maharaja was sitting was cold, air-conditioned and that there were dark curtains all around.

Bhandari recalls, “His Highness had just read a few lines of my papers when he made a whistling sound. I thought the whistle was for some pet dog. But I was astonished that from behind the curtain an officer wearing an achkan and a turban on his head came into the room in response to the whistle. He was crouching almost half bent in the presence of the Maharaja.

The Maharaja made a one word order ‘Thandi’ which meant cold drink. The officer bent low and retreated without turning his back to the Maharaja. I later learned that this officer was Rai Bahadur Boota Ram, MBE, a favourite of the Maharaja, and a sort of minister-in-waiting and notorious for doing odd jobs for the Maharaja. I was struck by such servile manner in which that officer had acted in taking an order of refreshment from the Maharaja.

My interview went off quite well and after 3–4 minutes the Maharaja surveyed me with a penetrating gaze. I gave him my assurance of loyalty and integrity. My interview was over. I got my appointment orders on the next day.”

The Development and Revenue Minister in Patiala Government at that time was Raja Hari Krishan Kaul, who was about 75. He had retired as a senior Commissioner of the Punjab government. He had joined service under the British as a statutory civilian. He was the elder brother of Raja Sir Daya Krishan Kaul. A noble and dignified gentleman he was famous for his orthodoxy in food. He did not eat in the company of anyone and took his food in the kitchen, thus avoiding pollution if served outside the kitchen and handled by anyone other than the cook who was always a Kashmiri Brahmin. Even when he invited people to dinner he would entertain them without taking his food with them. He would only take some dry fruits when presiding over the meal. He made no departure from this rule even when he was entertaining the senior-most British officers. Because of this Raja sahib was respected all the more.

“Hari Krishan Kaul was a widower and his only passion was to work on the files submitted to him. He went into minute details in every case and worked very hard,” recalls Bhandari, “He was a chain smoker and either a pipe or a cigar was always in his mouth. Raja sahib was a model of honesty. He kept a separate stenographer for his private work. No one could tempt him to take any undue advantage. He treated me like his son and took me in his car whenever he went on official work.”

After completion of his three years of service a motivated propaganda encouraged by the new Maharaja against Bhandari started saying he was a pampered officer, who abused his position. “So I resigned and after paying my fervent respects most sorrowfully to Raja sahib, left service of the Patiala government.” Raja Hari Krishan Kaul also left service of the Patiala State, after a few months.

During his tenure, Bhandari negotiated the erection of an ACC factory at Surajpur which was then in Patiala territory and only five miles away from Chandigarh. Its capacity was initially 60,000 tons and later enhanced to one lakh tons. The supply of limestone from Mallapahar through one ton containers was by an aerial ropeway from the nearby hill to the factory. The factory soon flourished. In addition to the setting up of the cement factory in Patiala territory, a number of mandis (markets) were set up and the old markets expanded. In addition, a lot of other development work was done which augmented revenues of the State. All this good work was of no avail in the atmosphere of driving out officers who did not belong to Patiala.

The ethos and ambience at Patiala during the princely rule were markedly regal; its reminiscences are of camphor-laden breeze playing upon Belgian glass bearing the State insignia at the entrance of Moti Bagh, of a forest of chandelier lights tinted in the hues of Bohemia, of the palace lake 2,000 ft in length and a handsome width as well, surrounded by a jungle and a mono rail; high electrified walls; with an island pavilion at its centre built for the heightening of pleasure; of the Dakotia Mahal in which lived 400 ladies, graded for their beauty; of the King playing Holi, the Indian festival of colours that marks the end of winter and a marble baradari drenched in the colours of saffron, brilliant green and the Indian rose; of shehnai players awakening the palace at dawn and moonlit gardens older than 100 years.

Patiala stood apart for its manners and courtly etiquette, which with the advent of Kayastha families from Delhi, Agra and Lucknow into the palace created a language blending Punjabi with Urdu … akin to vigour fortified by polish. And Moti Bagh Palace resounded with the voice of Bade Ghulam Ali Khan who established a distinctive gharana for Patiala.

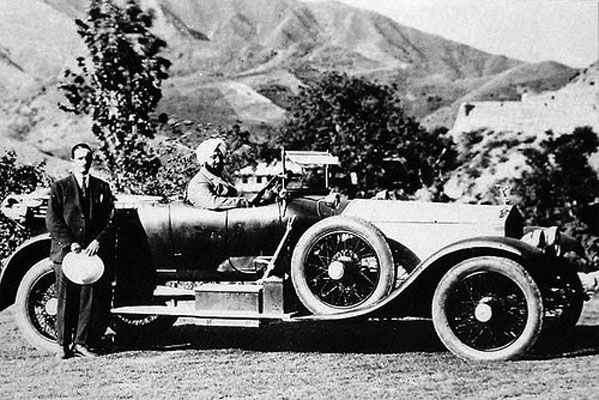

The Patiala rulers were great equestrians and Maharaja Bhupendra Singh, according to chroniclers, on receiving the British Resident at the railway station at Rajpura, on a wager, raced the train carrying the Resident, and was well in time to formally receive him within the Patiala State borders.

In the fairy tale kingdom of Patiala, the subjects of the king had little to do with life in the palace apart from catching a glimpse of the royal cavalcade on its way to some splendid event.

The vast territory of Patiala was largely prosperous; the durbar had little to do with the villages, and for the king, governance was another engagement in the palace.

(The writer is a retired IAS officer and author of the book: And What Remains in the End: The Memoirs of an Unrepentant Civil Servant.)