We have all heard the phrase: ‘out of the mouths of babes’. This was one reason I had not picked up Malala Yousafzai’s book, I Am Malala, all these years. Yes, she had lived through a terrible experience — being shot at by Taliban terrorists — at age 15 with tremendous courage and had come through it all to become a role model especially for young people and women. Ever since, she had been in the news and had been seen to have met influential people and received international honours, including the Nobel Prize when she was just 16. But… but, she was just a kid! I couldn’t have been proved more wrong.

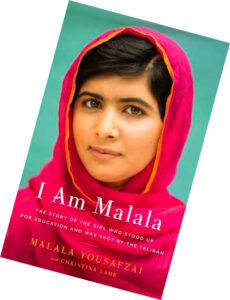

Recently, I watched a programme on YouTube showing Malala addressing the Canadian parliament after being conferred honorary citizenship of that country. It was old news, but I was blown away. By her simplicity, composure, humour, restrained oratory, powerful message and, more than anything else, her spirit of forgiveness. At this time of the season, when people of different faiths celebrate peace, goodwill, enlightenment and devotion, it seemed as though the universe were leading me to her. That’s how I started reading I Am Malala, which she has co-authored with journalist Christina Lamb, whose book, Farewell Kabul, was featured in this column a couple of months ago.

What an education the book is, full of insightful observations that sweep away dust in the mind. It talks about the history of the region, the Swat Valley that straddles both Pakistan and Afghanistan; the people and their beliefs and practices; the growth of the Taliban; social conditions and conditioning, the lack of education and basic facilities; mystical mountains, clear skies and running water, and sometimes piles of garbage; the efforts to educate children, especially girls; growing up in a loving environment in a society rigid with rules; a father who defies stereotypes and a daughter who follows suit, yet who are both very much products of their circumstances; the love for reading; being a girl; speaking up and dressing up; politics and holding political views; the generosity and support of strangers…

No wonder the book was declared nonfiction book of the year when it was published.

Christina Lamb, as we already know, comes with firsthand knowledge of the region. Malala, we realise, is extraordinary. And although a lot of the background information is clearly the work of the journalist, it is Malala’s voice we hear. You see that she wasn’t just some random kid who got in the way of the Taliban. Even before she turned 13, she was politically aware, speaking publicly in support of the importance of educating girls and questioning injustices in society. In this, she was deeply influenced by her father, Ziauddin, who took the lead in the community and beyond in opposing social injustices and speaking out against the violence perpetrated by the Taliban.

As you read, you get a strange but distinct feeling as if Malala was ‘chosen’ to be at the receiving end of bullets shot at her pointblank by two men who stopped the van bringing her and other children back home from school on October 9, 2012. ‘Who is Malala?’ they asked and when she identified herself, they fired three shots. Malala slumped forward; two other girls were also hurt but their wounds were less grievous.

While all these and the story of how Malala was flown on the private plane of a Saudi royal for treatment in the UK and her gradual recovery read almost like fiction, it’s the painting with words of the larger canvas that is riveting. You are compelled to pay attention as, for instance, you read: ‘Children in the refugee camps were even given school textbooks produced by an American university which taught basic arithmetic through fighting. They had examples like, “If out of 10 Russian infidels, 5 are killed by one Muslim, 5 would be left” or “15 bullets – 10 bullets = 5 bullets”.’

A simple paragraph like the following resonates with us but it also tells a troubling story: ‘It was school that kept us going in those dark days. When I was in the street it felt as though every man I passed might be a talib. We hid our school bags and our books in our shawls. My father always said that the most beautiful thing in a village in the morning is the sight of a child in a school uniform, but now we were afraid to wear them.’

Despair seeps through simple words: ‘People had lived by the river in Swat for 3,000 years and had always seen it as our lifeline, not a threat, and our valley as a haven from the outside world. Now we had become “the valley of sorrows”, said my cousin Sultan Rome. First the earthquake, then the Taliban, then the military operation and now, just as we were starting to rebuild, devastating floods arrived to wash all our work away. People were desperately worried that the Taliban would take advantage of the chaos and return to the valley.’

And a few lines later, you see Malala reaching right for the fundamentals: ‘While all this suffering was going on, while people were losing their loved ones, their homes and their livelihoods, our president, Asif Zardari, was on holiday at a chateau in France. “I am confused, Aba… What’s stopping each and every politician from doing good things? Why would they not want our people to be safe, to have food and electricity?”’ Questions that echo around the world.

It’s not just conflict or poverty that creates refugees; it’s government policies and people’s attitudes too.

It’s been some years and Malala is now a young woman. But she continues speaking up and asking questions, and has used her prize money to set up a fund to help children, especially girls and women. This prompted me to read, along with I Am Malala, a book in which she shares stories from refugee girls around the world, called We Are Displaced. Noting that according to statistics from the UNHCR more than 44,000 people a day are forced to flee their homes, Malala urges us, among other things, to ‘be kind to a new student who has been displaced and is starting over… Know that empathy is key.’ And we in India know too well that it’s not just conflict or poverty that creates refugees; it’s government policies and people’s attitudes too.

Malala was 16 when she was invited to speak at the United Nations: ‘I did not write the speech only with UN delegates in mind; I wrote it for every person around the world who could make a difference. I wanted to reach all people living in poverty, those children forced to work and those who suffer from terrorism or lack of education. I called on the world’s leaders to provide free education to every child in the world. “One child, one teacher, one book and one pen can change the world.”’

Zaynab, who fled war in Yemen and eventually settled in the US, met Malala after a screening of the film He Named Me Malala. She says she felt she was meeting a movie star. ‘But then,’ she says, ‘she sat down and started asking us questions, and I realized, She is just like us.’

If a girl, just like us, can touch so many lives and make us think about the need for change, what better purpose can books serve?

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist.