Every time August 15 comes along, there are events galore to remind us that it’s time to wave the flag and feel all patriotic. An organisation dedicated to the welfare of senior citizens decided to do something different: they planned a panel discussion among people who had actually lived through that momentous period in history leading to the special day in 1947. They were invited to share their experiences and thoughts just before and after Independence so that young people would get a glimpse of lived history. It was moving to listen to their stories and I felt a pang as I saw them gamely negotiate the challenge of using technology in order to make the online event happen. That’s the stuff our grandparents were made of.

However, it triggered a memory that continues to shame me. Some years ago, it so happened that a friend was working on his doctoral thesis. The topic revolved around Partition literature. Casually I remarked, “Oh no, not that again. When will we ever move on?” I will never forget the expression of incredulity followed by disappointment on his face. Immediately contrite, I tried to apologise, but the words had been spoken.

Yes, in that split second, I realised that separation from the homeland is one of the most painful and unforgettable experiences of life. Living in faraway Madras, I had no clue as to the extent of its impact on thousands and thousands and thousands of families living both in India and in Pakistan. We continue to experience the consequences of those political manoeuvres. This pain is brilliantly evoked in Saadat Hasan Manto’s short story, Toba Tek Singh. It’s a piece of writing that talks about a dilemma confronting the two new nations upon Partition: what to do with the mentally-ill housed in asylums on both sides of the border? Set in an asylum in Lahore, it brilliantly satirises the event through the reactions of various inmates, focusing on one in particular, Bishan Singh, from a village called Toba Tek Singh, incarcerated for fifteen years. His feet are swollen because he never lies down and he goes around spouting gibberish.

To quote a little from the story, which is best read in the original Urdu, or at least Hindi: the inmates “…had no idea where Pakistan was. That was why they were all at a loss whether they were now in India or in Pakistan. If they were in India, then where was Pakistan? If they were in Pakistan, how come that only a short while ago they were in India? How could they be in India a short while ago and now suddenly in Pakistan?” In fact, one of them is so bewildered he climbs up a tree and says he doesn’t want to live in India and Pakistan, he will make his home on the tree.

You don’t feel like laughing, however ludicrous the scenario, because the story unravels intangible but bitter aspects underlying Partition and, by extension, of separation from homeland, exile, forced migration… It impels the reader to think about what’s happening around the world today where, for a host of reasons, people are having to flee their homes.

At one point, Bishan Singh is very confused because no one is ever able to tell him where his hometown, Toba Tek Singh, is: “…nobody seemed to know where it was. Those who tried to explain themselves got bogged down in another enigma: Sialkot, which used to be in India, now was in Pakistan. At this rate, it seemed as if Lahore, which was now in Pakistan, would slide over to India. Perhaps the whole of India might become Pakistan. And who could say if both India and Pakistan might not entirely disappear from the face of the earth one day?” The best answer to Bishan Singh’s question comes from an inmate who “had declared himself God”. He says Toba Tek Singh is “neither in India nor in Pakistan. In fact, it is nowhere because till now I have not taken any decision about its location.”

As the story reaches its dramatic conclusion, you are stunned by the layers of meaning it contains. Manto was known for this. He was a writer whose ideas were way ahead of his times. He was radical, he was forthright, he was searing in his observations, and the guardians of society, both state and self-appointed, didn’t know what to do with him. So, they reviled him, they imprisoned him, they proscribed his writing. Remember Perumal Murugan? How he was so hounded by the state for his writings that he declared one day that he would stop writing? Luckily for us, he rescinded on that decision. Lucky for us, Manto continued to write. You can even listen to a reading of Toba Tek Singh online. Do look for it, you will not regret it. Don’t worry if you don’t understand Urdu. Read the story in English first. Then listen.

Through all the instances of separation, dislocation, exile, migration, life still goes on. This shines through in a book I recently purchased when my local bookstore announced that it had gone online. City of Jasmine by Olga Grjasnowa is translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire. It revolves around the actions and decisions taken by three young people — Amal, Hammoudi and Youssef — when civil war rips apart their homeland, Syria. Set largely in Damascus, the reader gets a sense of young peoples’ lives even as bombing and shelling lay the city low. They still dream of becoming actors and doctors and falling in love; they try to pursue these dreams. The reality is harsh, though. The book provides perspective to impressions formed mostly on the basis of news reports.

When we speak of assimilation and integration, books on these subjects remind us that attachment to the homeland is as intrinsic as breathing. You are alive as long as you breathe, you breathe as long as you are alive. So too, the longing for home courses through your consciousness as long as you are alive.

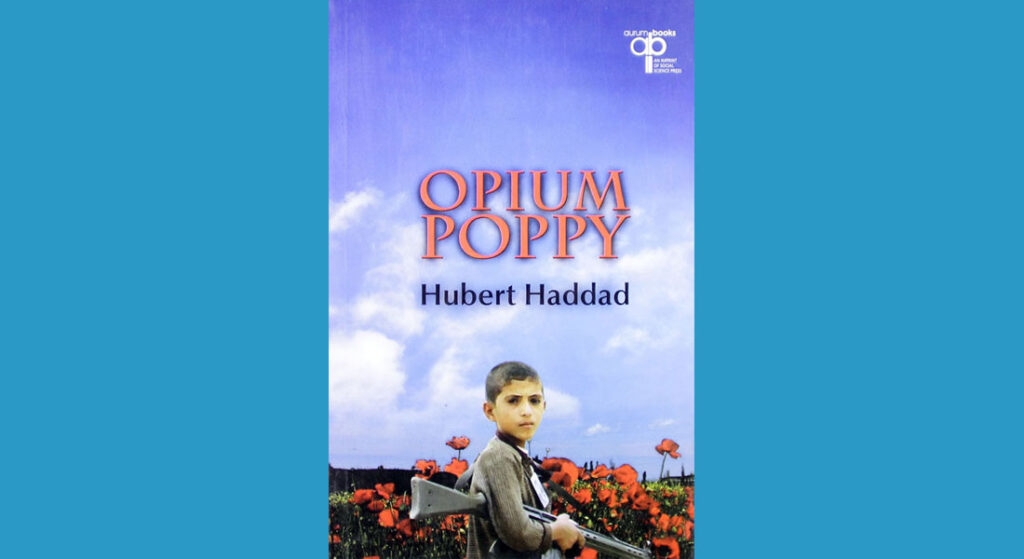

I don’t quite remember how the book, Opium Poppy, by Hubert Haddad came into my hands. Translated from the French by Renuka George, it is the stomach-churning story of a small boy, Alam, who escapes from war-torn Afghanistan and the opium trade to become a refugee in France, living among other young refugees like himself, in the shelter of a bridge. There, instead of protection, he becomes a victim of the heroin trade and political discrimination. It’s a slim book, a mere 126 pages, but much of it is almost impossible to imagine. Yet, we know this is happening, even today, if only we keep an ear open to hear their voices. As Maya Angelou writes in her poem, The Caged Bird:

The caged bird sings / with a fearful trill of things unknown / but longed for still and his tune is heard /

on the distant hill for the caged bird / sings of freedom.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist.