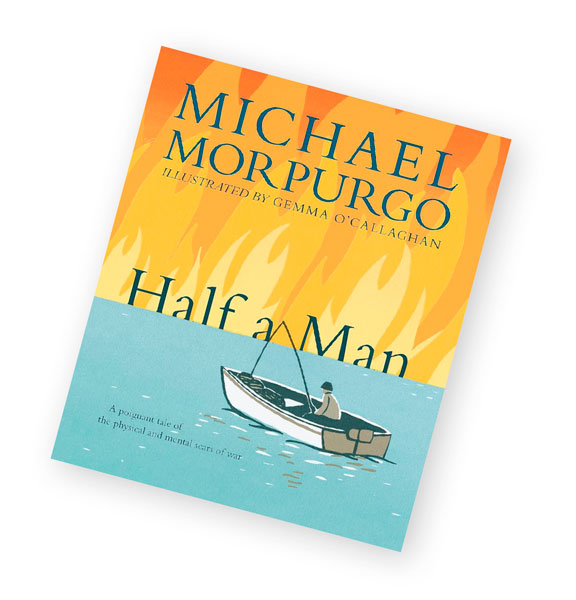

I was at my desk the other day, doing my usual thing, reading a bit, dreaming a bit, watching my favourite shows a bit when out jumped a book from the bookshelf in front and landed plonk on my head. Startled, I managed to avoid damage to both book and self, and looked to see what had caused the sudden activity. There had been no knocking sound on the other side, no tremor. Bemused, I gazed at the front cover: it displayed Half a Man, sort of setting into the sea with tall flames rising from the surface of the water. Written by Michael Morpurgo, a well-known writer and poet whose books are gobbled up like samosas and illustrated by Gemma O’Callaghan, it has the most vivid endpaper in a gorgeous orange that sets off brilliantly black and white silhouettes of birds in flight.

I opened the book and flipped through its pages — just about 60 or so — profusely punctuated with pictures in colour. I started reading: ‘When I was very little, more than half a century ago now, I used to have nightmares. You don’t forget nightmares. This one was always the same. It began with a face, a twisted, tortured face that screamed silently, a face without hair or eyebrows, a skull more than a face, a skull which was covered in puckered, scarred skin stretched over the cheekbones.’ I read on till the end of the book; its simple, lucid prose was both profound and moving, and resonated with layers of meaning.

The narrator of the story is a boy called Michael — and no, this is not about Michael Morpurgo, although it is inspired by true events. Michael shares with the reader observations, comments and feelings about his grandfather whose impending visit always made his parents feel extremely tense. Grandfather was injured badly during the second world war; his burn injuries left him with literally only half a face and barely any fingers. He received arduous and lengthy treatment and was eventually rehabilitated, but coming home to his family found them unable to come to terms with him, or rather, how he looked. They were, to put it mildly, shocked by his physical transformation. They took care of him, of course, but they avoided looking at him, his face, they didn’t talk to him. Over the years, therefore, Michael’s grandfather retreated further and further into his shell.

The simple, lucid prose of Half a Man is both profound and moving, and resonates with layers of meaning. The cadence of its prose and the power of storytelling is compelling.

Only Michael was different. ‘…I’d sneak a crafty look. And very soon that look became a stare,’ he says. ‘I was never at all revolted by what I saw. If I had been, I could have looked away easily. I think I was more fascinated than anything else, and horrified too, because I’d been told something of what happened to him in the war. I saw the suffering he had gone through in his deep blue eyes — eyes that hardly ever blinked,

I noticed. Then I’d feel my mother’s eyes boring into me, willing me to stop staring, or my father would kick me under the table.’

The child’s natural curiosity and spontaneous empathy gradually unravel grandfather’s story and eventually enable him to help the family understand. For instance, why he doesn’t smile — he can’t because the skin around his mouth and on his face is tight; why he is so silent — because he feels alone and rejected. In the end, thanks to Michael, his family members reclaim the warmth of their relationship. Gannets, among the largest seabirds in the North Atlantic, also feature in the story, and not just on the endpapers! Grandfather says gannets bring good luck.

This is the gist of this little work of fiction. However, like other ‘little’ books such as The Little Prince by Antoine de St Exupery, Jonathan Livingstone Seagull by Richard Bach, or The Snow Goose by Paul Gallico, this one too works at the level of metaphor, for life and experiences, and specifically war. Like the titles mentioned here, this book too is as much for the soul as for the cadence of its prose and the power of storytelling.

Dring World War II, Dr Archibald McIndoe, a plastic surgeon, innovated ways to more effectively treat burn injuries suffered by pilots, and helped them reintegrate into the community.

At the simplest level, Half a Man is about war and the physical and mental scars it leaves behind; however, it also resonates with other ideas such as the consequences of enmity; the corner into which the differently-abled are pushed owing to fear, lack of awareness. It’s the kind of book in which the reader will find new insight upon every reading. It is a work of fiction, yes, but the world it creates is palpable, tangible, real. And the doctor who attends to Michael’s grandfather is an actual person: ‘It was him that did it, put us back together, and I’m not talking about the operations. He was a magician in the operating room, all right. But it’s what he did afterwards for us,’ grandfather tells Michael. ‘He made us feel right again inside, like we mattered, like we weren’t monster men.’ Whereas his own daughter ‘didn’t look at me the same, didn’t speak to me like I was normal…. She still loved me, I think, but all she saw was a monster man.’

plastic surgeon

An article of May 2016 in the blog site LibrisNotes remarks that the doctor mentioned in the book as Dr McIndoe, was, in fact, Dr Archibald McIndoe, a plastic surgeon. It says he innovated ways to more effectively treat burn injuries suffered by pilots who were casualties of the second world war, and helped them reintegrate into the community. In fact, Dr McIndoe placed great emphasis on the need for such people to find their rightful place in society. During the war, he also founded the Guinea Pig Club for exactly such a purpose, to help patients recover not just physically but also mentally and socially. If you check out the copyright page, you will find that it is dedicated to Eric Pearce, “one of the very last of McIndoe’s ‘Guinea Pigs’”.

This piece of information reminded me of S Ramakrishnan, the founder of Amar Seva Sangam. As a fourth-year engineering student, he wanted to join the services; he signed up for the admission process. During the last round of the naval officers’ selection test, he suffered an injury that left him paralysed neck down. He was immediately taken to the defence hospital for treatment where he did not just have to deal with physical pain, but also with the knowledge that he had become a quadriplegic. After months of treatment and recuperation, he returned home to Ayikudy in Tirunelveli district. There he founded the Amar Seva Sangam in order to treat and rehabilitate children with physical disabilities. Ramakrishnan named his institution after Air Marshal Dr Amarjit Singh Chahal, who had not only treated him at the defence hospital, but also given him moral support and encouragement all through that trying time. Established in 1981, the Amar Seva Sangam works to empower and enable the physically and mentally-challenged live, as their vision statement says, ‘in a proactive society where equality prevails irrespective of physical, mental or other challenges with the rest of society.’

Do you remember Dashrath Manjhi? He was a villager who lived near Gaya. For 22 years he chipped away at a mountain until he managed to create a passage that drastically cut down travel time to the nearest hospital. Truth is more amazing than fiction; Half a Man proves that in its own way.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist