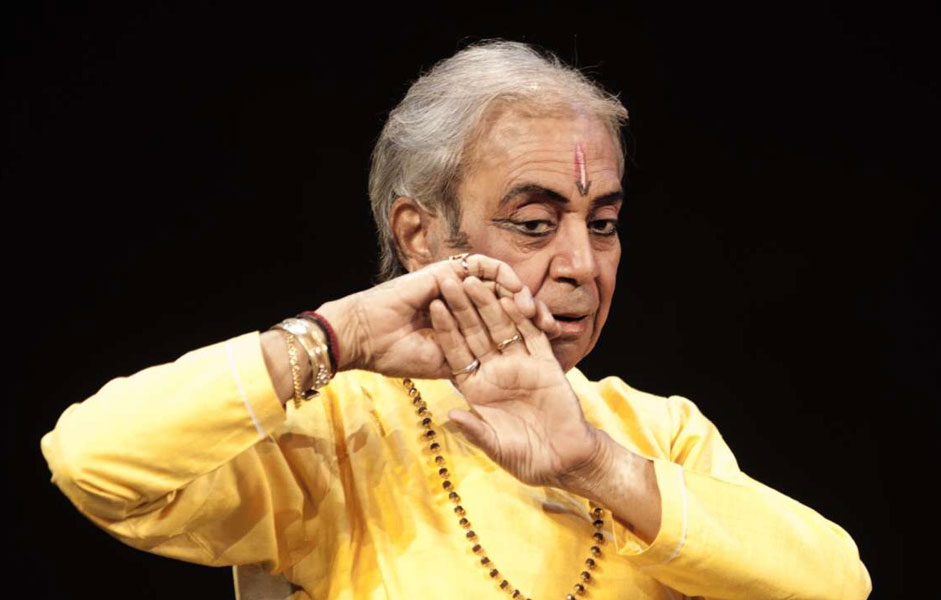

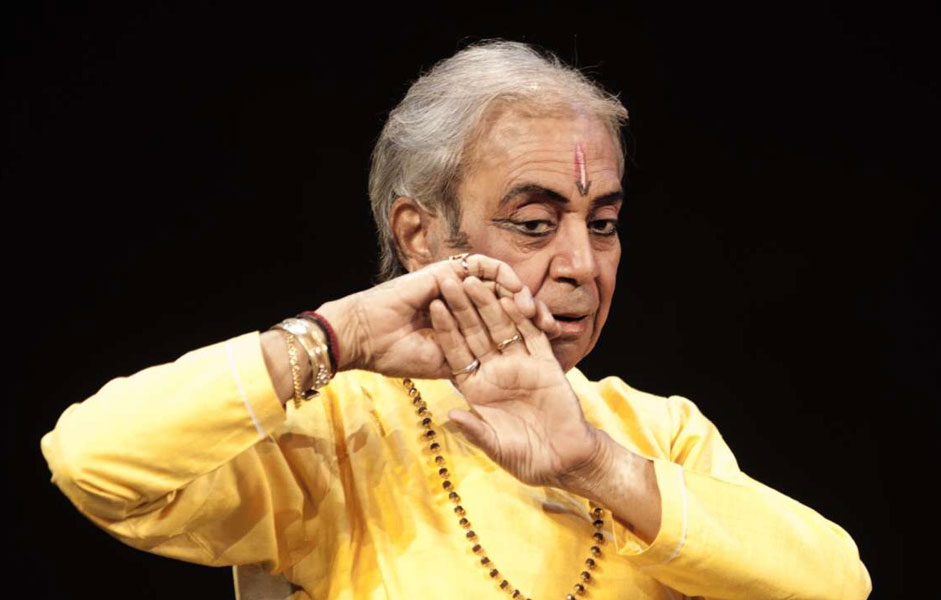

I have a distinct recollection of the renowned Kathak dancer and choreographer Gopi Krishna visiting our house when I was very young and we watched the film Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje which had amazing Kathak dances choreographed and performed by him. A clearer memory of Kathak is from the dances in the epic movie Mughal-e-Azam which released in 1960. The gorgeous costumes, expansive gestures, movement of eyes and eyebrows and the graceful pirouettes left an indelible impression on my mind. My understanding and admiration increased manifold when I had the good fortune to witness great performances by stalwarts like Pandit Birju Maharaj, Kumudhini Lakhia, Uma Sharma, Ranee Karna, Shovana Narayan, the late Pandit Durgalal and many others. The intrinsic beauty of Kathak dance was akin to the ethereal beauty of the Taj Mahal. The combination of delicate nuances and strong rhythmic footwork of the dance was as extraordinary as the intricately carved engravings in the arches and lattices made of solid marble. Little wonder that Shah Asad Rizvi says of Kathak: “Dance is the narration of a magical story: that recites on lips, illuminates imaginations and embraces the most sacred depth of souls.”

The intrinsic beauty of Kathak dance is akin to the ethereal beauty of the Taj Mahal.

Every classical dance style of India has its own distinct identity. The term Kathak is derived from the Sanskrit word Katha which means story, and Kathaka which means the one who tells a story. The wandering bards, Kathakars, communicated stories from the great epics and ancient mythology through dance, songs and music in a manner similar to early Greek theatre. Kathak dance started as a performing art during the Bhakti movement by extolling the virtues of Lord Krishna and survived as an oral tradition. During the 16th and 17th centuries it gradually transitioned and adapted to find acceptability in the Mughal courts. It evolved artistically by incorporating Persian and Central Asian themes to the existing repertoire. Like most dances in India, Kathak too declined during the colonial era but resurfaced after independence with a unique blend of Hindu and Muslim cultures which found a pan-Indian appeal.

Researchers suggest that Kathak originated in Benares and migrated to Lucknow, Jaipur and other parts of northern India. The Benares gharana, believed to be the oldest, was started by Janaki Prasad who hailed from a family of famed dancers and is credited with inventing the bols or mnemonic syllables of Kathak dance. The Lucknow tradition attributes the style to a devotee named Ishwari from the Handia village in Allahabad who had a vision of Lord Krishna appearing in his dream and asking him to develop dance as a form of worship. Ishwari taught his descendants, who in turn continued to teach the dance through an oral tradition to six generations. Bindadin Maharaj and his brother Kalika Prasad brought a renaissance to the Kathak dance and raised it to a highly polished level. The Jaipur gharana traces its origins to Bhanuji, a renowned Shiva Tandav dancer, who was inspired by Krishna when he visited Vrindavan. He returned to Jaipur with his grandsons Laluji and Kanhuji and started teaching the dance. The theme centred primarily on legends from the Bhagavatha Puranas extolling the divine Krishna, His lover Radha and the gopis or milkmaids. The depiction of the love between Radha and Krishna was symbolic for the love between the Atma, the soul within and the Paramatma, the Cosmic soul.

An exclusive aspect of the footwork is deftly making each bell of the ghungroos tied to the ankles resonate in perfect synchronisation to the tabla beats.

During the Mughal era, Kathak became more of an entertainment by courtesans for the aristocrats and the religious themes were replaced by more abstract dances. More prominence was given to elaborate pure dance pieces with intricate footwork patterns known as Tatkars and Tukdas. It evolved further by imbibing the influences of several cultures like the swirling movement of the Sufi dancers and the exotic costumes, jewellery and even a transparent veil worn by medieval harem dancers. But during the British colonial period the courtesans were ostracised as “nautch girls” and Kathak dance began to decline due to lack of support and patronage. Since the stigma was for only for female dancers, the Kathak teachers continued to train boys to perform and preserve the tradition. The post-colonial era witnessed a healthy emergence of a culturally enriched dance style that gained popularity across India.

A modern recital consists mainly of three segments that are performed with a live orchestra. It begins with a salutation or vandana to God, the Guru and the musicians. This is followed by a pure dance recital where the dancer displays virtuosity through speed, precision and artistry. It starts with a Thath which is the slow graceful movement of eyes and hands and gradually builds up momentum with a series of elaborate sequences that end in a freeze. Sometimes the dancer interacts with the audience with a Padhant, which is a rhythmic enunciation of the dance syllables before demonstrating it with Tatkar or footwork. An exclusive aspect of the footwork is deftly making each bell of the ghungroos tied to the ankles resonate in perfect synchronisation to the tabla beats. Progressing from the micro to the macro, the highlight of a Kathak performance is the gravity defying spins known as chakkars where the dancer circles around the stage, dancing circles in rhythmic patterns and finishes with a dramatic flourish. The costume of the female dancer is designed to enhance the beauty and grace of the pirouettes which earn maximum applause from the audiences.

Pali Chandra, Kathak guru and Director of the Gurukul Dance School based in Dubai, Switzerland and Bengaluru, says, “The artist and the activist has truly come a full circle in the last 25 years of Kathak! I am now exploring the other unique facets of this classical dance form. Our team members are researching on more intense themes like depression, child abuse, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and how dance can express the impact of trauma these diseases can bring. Kathak has immense potential to educate and build awareness around these topics. About time we start making substantial difference and build an empathetic audience. And the audience has responded beautifully to this across continents.”

Kathak Kendra, a premier dance institution which is a unit of the Sangeet Natak Akademi, India’s national academy of music, dance and drama, New Delhi, is primarily dedicated to teaching Kathak and also offers courses in Hindustani vocal music and the percussion accompaniment, Pakhawaj. Established in 1955, Pandit Shambhu Maharaj, the celebrated guru of the Lucknow gharana, used to be the head of the department. He was a noted exponent of the bhava (emotive part) who revived several classical thumris and bhajans and added them to the Kathak repertoire. He trained several renowned dancers like Kumudini Lakhia, Damayanti Joshi, Bharti Gupta, Gopi Krishna, Maya Rao and Sitara Devi. After his demise in 1970, his nephew Birju Maharaj, a noted Kathak dancer and guru in his own right, became the Head of Faculty and remained the Director of the institution till 1998. He adapted the dance, which used to be staged for small gatherings in temple courtyards or Mehfils, to appeal to large gatherings in the modern proscenium theatre, and choreographed several noteworthy ballets. Kathak, which was essentially a solo-dance format, was gradually adapted for thematic group presentations to cater to a cross-cultural audience. Some of the notable ballets presented by the ballet unit repertory wing are Taj ki Kahani choreographed by Krishna Kumar with music by Amjad Ali, Shan-e-Audh, Kumara Sambhav and Dalia choreographed by Birju Maharaj with music by Dagar brothers and mythological themes like Govardhan Leela, Makhan Chori and Phag Bhara.

Birju Maharaj performed these ballets all over the world along with the dancers of Kathak Kendra and brought worldwide recognition to this traditional dance form. The living legend and a great perpetuator of this art form says, “I wish to create an atmosphere which aims at bringing back to dance all that sensitivity and delicate aesthetics which are threatened in this age of violence. Art has to exult and elevate.”And the inherent beauty of Kathak dance continues to do just that. The dance has adapted to the changing times by modernising without compromising on traditions. It has moved beyond the Radha Krishna theme by including classics of poet Kalidasa, Sufi songs, thumris and compositions of contemporary writers. Kathak dance survived and will continue to live on because “stories have to be told or they die, and when they die, we can’t remember who we are or why we’re here,” as Sue Monk Kidd rightly said.