In 1937, a Bombay business wanted the best and most prestigious singer to perform at a family event. Kundan Lal Saigal was offered ₹25,000 for a few hours. But he preferred to keep his promise to a poor lighting assistant, whose daughter was getting married. Saigal sang all night there, ignoring the ₹25,000 offer. “The badshah of singers had the voice of an angel and a heart of gold,” said Naushad.

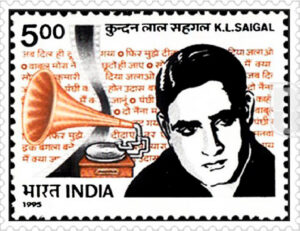

Saigal’s was “the voice of the century”, a voice so powerful that it could break recording needles! He was the first great singer-actor and the first superstar of Bollywood music.

His god-like status as singer is remarkable for many reasons.

He was active for barely 15 years (1933 to 1947) and sang just 185 songs (including 142 film songs in 39 films in six languages) in rudimentary sound recording facilities. He had little music training. But he held a whole nation in thrall. Classical maestros like Ustad Faiyaz Khan were stunned by the elemental force of his music. In 1932, a non-film song of his, Jhulana jhulao ri, sold half a million records, in an era when few people owned record-players.

Saigal’s was the voice of the century, a voice so powerful that it could break recording needles!

Lata Mangeshkar as a kid was so besotted with Saigal, she said she wanted to marry him! In his spectacular stage shows, Kishore mimicked everyone — but never Saigal. That would be a sacrilege. Said Talat Mehmood of Saigal — “What pronunciation, what throw of voice, what depth of feeling, what voice control — I couldn’t touch him!” Suraiya was so overawed at the idea of singing a duet with him in the 1947 Parwana that the composer had to drop the duet!

During the 1930s and 1940s, Bollywood believed that a singer had to sound like Saigal to be effective: he was the sole barometer of quality and impact. Mukesh began his career with the haunting Dil jalta hai to jalne do (Pehli Nazar, 1947), a song so Saigal-like that Saigal remarked “I don’t remember singing this song”! C H Atma adopted the Saigal style for the immortal Preetam aan milo (sung for a private album in 1945), so did Surendar in that iconic duet with Nur Jehan, Awaaz de kaha hei (Anmol Ghadi, 1946).

For some 45 years (starting from the mid-50s), the most important time of the day for thousands of film music fans was 7.57am, when Radio Ceylon would play a song of K L Saigal, and this had an incredible nationwide appeal. People arose not to the twittering of birds but to the sound of Saigal’s voice, says film historian Manek Premchand.

Saigal was born on April 11, 1904, in Jammu, the third of four sons. His father Amarchand Saigal was the tehsildar of a small town. The boy showed a keen interest in singing and could copy any song he heard. He often accompanied his mother Kesar Devi, an accomplished singer of bhajans, to religious gatherings. He would pick up music from folk singers and wandering minstrels and even from dancing girls of Jammu being trained in their kothas. At 10, he played the role of Sita at Ram Lila functions.

But his father regarded him a wastrel, often scolding and spanking him for his laziness, laxity in studies, poor performance in exams, unkempt appearance and craze for music.

The young boy was distraught when his voice cracked at 12, and he was unable to sing. His mother took him to a mystic Sufi who had blessed the boy at birth and later predicted a bright future for him. The mystic asked young Kundan to practise two secret chants of his sect, zikr and riyaz, which would ensure spiritual enlightenment and enable him to transform emotion to song. Kundan stopped singing for two years but perfected the zikr and riyaz to obtain a rich, nasal baritone.

Saigal once told a close friend “I was born at the age of 12 in a peer’s hut one windy evening in Jammu.”

When his father retired, the family moved to Jalandhar. Passionate about music and stifled by life in that city, Saigal left home. He took up sundry jobs and listened to music and sang whenever possible. He wandered about in several cities. He served as a timekeeper in the Railways, sold Remington typewriters and saris, and was manager of a hotel in Shimla. During these years of wanderlust, he often charmed people at homes and soirees with his exceptional music.

In Calcutta, Saigal got introduced to B N Sircar, who had just started New Theatres. He was not impressed by the lanky gauche man nervously clutching his kurta. But he was astounded when Saigal sang. Result: a five-year film contract, on a monthly salary of ₹200.

Saigal’s first three movies with New Theatres flopped. However, fortunes turned with the 1934 Chandidas — its pathos-filled romantic song Prem nagar was a hit. The 1935 Devdas was a national sensation. Balam aye baso more man mein was a romantic gem that charmed one and all. Dukh ke din bitat nahin was the cry of a person sunk in the abyss of despair. Millions wept with Saigal, said Baburao Patel.

Success followed success (with films like President, Street Singer, Dushman etc). Those who had scoffed at the unkempt youngster from Jalandhar — he was described as Frankenstein when he first entered movies — vied with each other to tap the gold in his throat. During a 1937 visit to Lahore for a stage performance, Saigal was lionised by adoring crowds. Cries of Kundan Lal Saigal zindabad rent the air.

He got married in 1934 to Asha Rani, a girl chosen by his mother. They had three children.

In 1941, an exodus occurred of film personalities from Calcutta to Bombay, and Saigal too made the switch. Chandulal Shah of Ranjit Movietone signed a three-movie contract with him at ₹1 lakh a movie. Saigal sang memorable songs in Bhakti Surdas (1942) and Tansen (1943). In 1944, he went back to Calcutta for My Sister with New Theatres. His last famous film was Shah Jahan (1946), where he sang Jab dil hi toot gaya, a blend of sadness, sweetness and intoxication, perhaps the song he is best remembered for.

Many Saigal songs belong to the pantheon of Bollywood immortals.

Examples:

- Ek bangla bane nyara (President, 1937)

- Babul mora (Street Singer,1937)

- Karoon kya aas niras bhaee (Dushman, 1939)

- Mai ka janoon kya jadoo hai (Zindagi, 1940)

- So ja Rajkumari so ja (Zindagi, 1940)

- Aye katib-e-taqdeer mujhe itna bata de (My Sister, 1943)

- Do naina matware tihare (My Sister, 1943)

- Jab dil hi toot gaya (Shah Jahan,1946)

Each of these masterpieces merits detailed analysis; here are just a couple of factual glimpses. In Ek bangla bane nyara (President) Saigal sings and jigs, elated at the idea of owning his own house. Millions of aspirational Indians empathised with this song. It was a favourite of Lata Mangeshkar, she often hummed it.

Through Mai ka janoon kya jadoo hai and Do naina matware, Saigal paid effervescent and melodious tributes to his screen sweetheart. Gham diye mustaqil and Jab dil hi toot gaya were heart-wrenching melodies. Babul mora (Street Singer) was historic. He insisted he would walk and sing, live on the street, like street singers, not in a studio. The mike followed in a truck. Music director R C Boral was astounded with the impact.

Saigal has been lauded as the “ghazal king”. He did more than anyone else to popularise romantic Urdu poetry, particularly at private events. And won recognition first as a ghazal singer. It is said that he immortalised Ghalib by singing his best ghazals in his own inimitable style, being well-versed in Urdu literature and a poet himself.

What made him such a phenomenon? It is said that he was the only singer who appealed to both mind and heart. Some attribute his power to the secret Sufi rituals he practised for two years which showed the path to God through music. Some critics have highlighted his tonal variations, and the way he caressed certain words while singing. He had 20 ways of singing a word!

Kanan Devi remarked that Saigal had a perfect pitch sense. He didn’t need the help of a veena or tanpura to set the right pitch. In fact, at recording sessions he would sing out a note and musicians would set their instruments accordingly. An amazing phenomenon!

In an illuminating interview with Kirit Ghosh, editor of the film magazine Jayathi, Saigal said, “I have no clear understanding of the grammar of music. I manage to sing because of a strong feeling about how certain sounds should feel in a given raga. I do not use ten notes if I can manage to do the same with one. That’s because I know very little.”

He said his “favourite raga is bhairavi. To know bhairavi is to know all the ragas.”

The author is a senior journalist and a member of the Rotary Club of Madras South.

Saigal lore: musical and personal

In 1937, Prithviraj Kapoor took Saigal to watch a hockey match in Mumbai featuring hockey wizard Dhyan Chand and his brother Roop Singh. But till half time, no goal had been scored, and Saigal expressed his disappointment. The brothers asked him if he would sing a song for them for every goal they scored in the second half. He agreed. They scored 12 goals! Two days later, Saigal sang 14 songs for them and gifted them expensive watches.

At his peak in 1938, he was invited to a large musical conference in Allahabad. Giants of classical music like Omkarnath Thakur, Ustad Faiyaz Khan, Vinayak Rao Patwardhan and others were present. Saigal stole the limelight as the audience clamoured for him to sing and asked for more and more. Carrying his mother in the audience in his arms, he said “They want me to sing more and more.” She shed tears of joy that her son who used to get mercilessly thrashed by his father was a public hero.

Generosity and humility were part of the Saigal legend. He never turned away any needy person. He once gave away his clothes to a beggar shivering in the rain and came home in shorts and vest. He parted with his diamond ring to a widow in distress he met in Pune. His wife told producers to hand over money due to Saigal only to his driver. An introvert, he shunned publicity. Fame left him unaffected. When praised for his music, he would say, “I have not killed a lion, just sung a song, forget it”.

Like Ghalib, Saigal was fond of the bottle. It is said that he suffered from sciatica, and liquor was recommended. It became a habit, then an addiction. Saigal often had a dose of “Kaali panch” before a song. Naushad says he persuaded Saigal to record Jab dil hi toot gaya both before and after a drink. Saigal was amazed that the pre-drink version was better, and wished he had met Naushad earlier.

In December 1946, Saigal’s health deteriorated (he suffered from cirrhosis of the liver and diabetes). He moved to his home town of Jalandhar, and passed away on January 18, 1947, driving out politics, communal riots and Pakistan from newspapers for a whole week.

He was just 43 when he died. But he lent soul and magic to Bollywood music. If today it is regarded as an awesome example of India’s soft power, it owes more to Kundan Lal Saigal than anyone else.