It is the early 1980s. Sashi, short for Sashikala, is almost 16 and set on becoming a doctor. She has three older brothers and one younger. They live with their parents in a happy home in Jaffna, at the northern tip of Sri Lanka. Their close friend, K, lives nearby. Just a year older than Sashi, he too plans to study medicine. And then the civil war erupts.

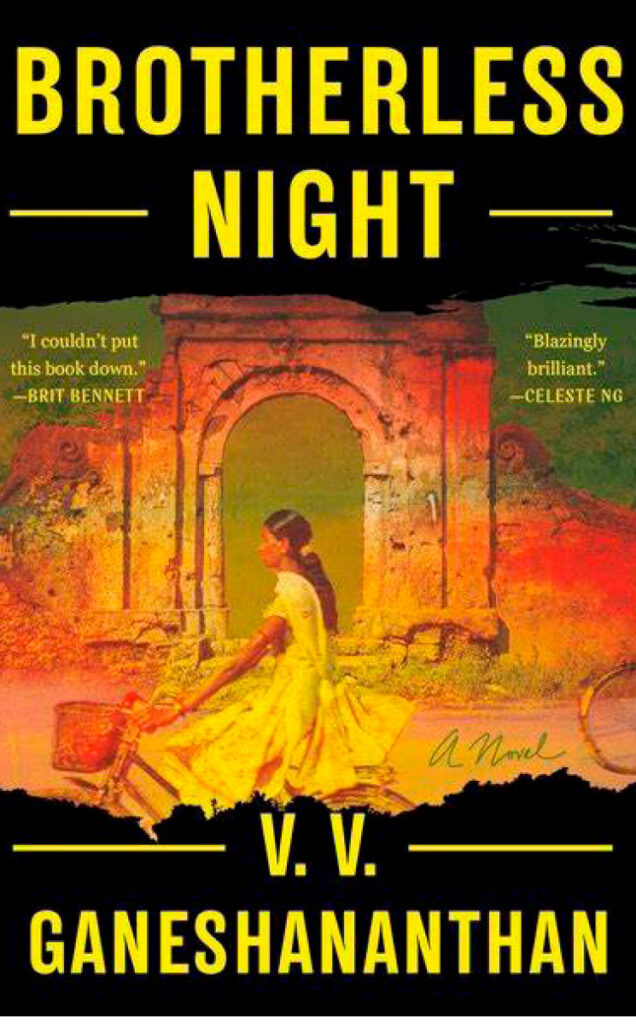

V V Ganeshananthan’s novel of this time, Brotherless Night, won the Women’s Prize for Fiction, 2024. One of the judges, Nigerian writer Ayobami Adebayo, says it is: ‘A powerful book that has the intimacy of a memoir, the range and ambition of an epic, and tells a truly unforgettable story about the Sri Lankan civil war.’ Sashi is the narrator of this work based on 16 years of research into a war that bled into the homes and hearts of ordinary people. Vasugi Ganeshananthan shows, through Sashi’s eyes, how this battle was not fought on some distant frontlines, but on streets, in homes, universities and libraries, in the marketplace and the forests. There was nowhere to hide. What had started as a demand for equal opportunities to work and to study, to recognise Tamil and Tamils, and to give their province autonomy ultimately became an unstoppable river of some one lakh bodies and over eight lakh displacements.

Datelined New York, 2009, Brotherless Night opens with the line: ‘I recently sent a letter to a terrorist I know.’ The narrator goes on to say, ‘We were civilians first. You must understand: that word, terrorist, is too simple for the history we have lived — … We begin with this word. But I promise that you will come to see that it cannot contain everything that has happened. … while I am no longer the version of myself who met with terrorists every day, I also want you to understand that when I was that woman, when two terrorists encountered each other in my world, what they said first was simply hello. Like any two people you might know or love.’

The import of these words registered with greater clarity only after reading the book; certain images too began to get sharper: gun-toting suicide bombers began to come framed in the context of families and secure homes, lines of LTTE cadres in military fatigues recalled schools and music and university libraries, unending streams of refugees arriving in Mandapam and Dhanushkodi transformed into persons with their own lives and loves. Superb storytelling by the author leads the reader to see the reality of trauma and psychological devastation.

As Sashi takes us through the years of her life as a school and then medical student in Jaffna, we see her hopes and dreams subserve the demands made by militants. Even before she can complete her medical degree, she is called upon to tend to wounded ‘Tigers’, as also civilians, in a medical clinic. As a ‘daughter’ of the revolution, and with two brothers in the movement, she has no choice. Besides, she is moved by moral responsibility as a future medical practitioner to treat the sick and the wounded, whoever they may be. Over time, she observes the actions of militants as well as of government troops and soldiers of the IPKF in all their shades of darkening grey, even as she has no time to mourn the death of a beloved elder brother caught up in anti-Tamil riots in Colombo. Simultaneously she sees the boy she loves slowly get drafted into the movement and eventually giving up his life in a hunger strike protesting the IPKF. He is referred to only as ‘K’. Meanwhile, she finds the perfect mentor in Dr Anjali Premachandran, her anatomy professor, who after initially supporting the iyakkam (movement), is disillusioned by its atrocities and becomes a fearless critic, even as she boldly stands up against ethnic soldiers.

You hear the voices of the people of Jaffna. Individual voices, individual horrors, personal tragedies and grief, the confusion among young people, the sundering and separating of families, the loss of relationships, the longing for security of home and garden and pets and friends, the eroding of trust, the uncertainty of life, even joys and dreams and laughter… Brotherless Night brings it all home. It tells the story of ordinary people, women, teachers, students, mothers, shopkeepers, with compassion.

There was a video rental place in Chennai that we frequented regularly. It was run by a Sri Lankan Tamil and, as I read the reference to ‘Jaffna eyes’ in the book, I recalled his eyes. Jaffna eyes. There, I once bumped into a man who looked very familiar but whom I didn’t know. It was Anton Balasingham, the LTTE ideologue. We were that close to the civil war.

You will meet him and many other familiar people in Brotherless Night. They are given different names but you will recognise them. K, for instance, is modelled on Thileepan, an LTTE military leader who died after going on hunger strike in support of demands the militant command felt India could force the Sri Lankan government to concede. He was just short of his 24th birthday. Anjali Premachandran is modelled on Rajani Thiranagama (nee Rajasingham), a professor of anatomy at the University of Jaffna and a human rights activist assassinated by the LTTE for calling them out for their atrocities. She was 35.

In an interview with the author on the Women’s Prize website, Ganeshananthan is asked what inspired her to write this novel. ‘I grew up listening to the stories of friends and family who had lived through this period in Jaffna,’ she says. ‘I was especially moved by the stories of women who worked to keep their families safe under brutal circumstances. I was also inspired by a nonfiction book called The Broken Palmyra, in which four Tamil professors at the University of Jaffna documented the violence civilians endured at the hands of majority Sinhalese-dominated state security forces, Indian peacekeepers, and Tamil militant groups.’ One of those professors was Rajani Thiranagama. The Broken Palmyra carries the following dedication: ‘In keeping with the wish expressed by the late Dr Rajani Thiranagama, this book is dedicated to the young men and women and the ordinary voiceless people, whose lives were destroyed to no purpose in the course of the unfinished saga of the people of Sri Lanka.’

Individual voices, personal tragedies and grief, the confusion among young people, the longing for security of home and garden and pets and friends… Brotherless Night brings it all home.

Speaking about the challenges of writing, the author says, ‘… much of the book’s source material is violent, and I was writing about the emotional effects of that violence. The biggest challenge of writing this book was depicting that brutality honestly, without either sensationalizing it or diminishing it. I needed to balance that with the stories of those who resisted.’

In an article for In Conversation (June 21, 2024), Prof Ankhi Mukherjee points out that while novels such as Traitor by child-soldier Shobasakthi, The Story of a Brief Marriage by Anuk Arudpragasam and The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Shehan Karunatilaka deal with this time period, none of them revisits ‘what Ganeshananthan calls the “country of grief” to show how women suffer and survive. They don’t touch on a “terrified and empowered” response such as Sashi’s to the vacuum created by missing fathers, brainwashed brothers, or radicalised friends.’

Brotherless Night moves the reader through its straightforward rendering of a charged and complex truth tale.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist