Konkani writer Damodar Mauzo’s stories gently lead the reader deep into a world of real experiences — multilingual, multicultural, multireligious — laced with irony.

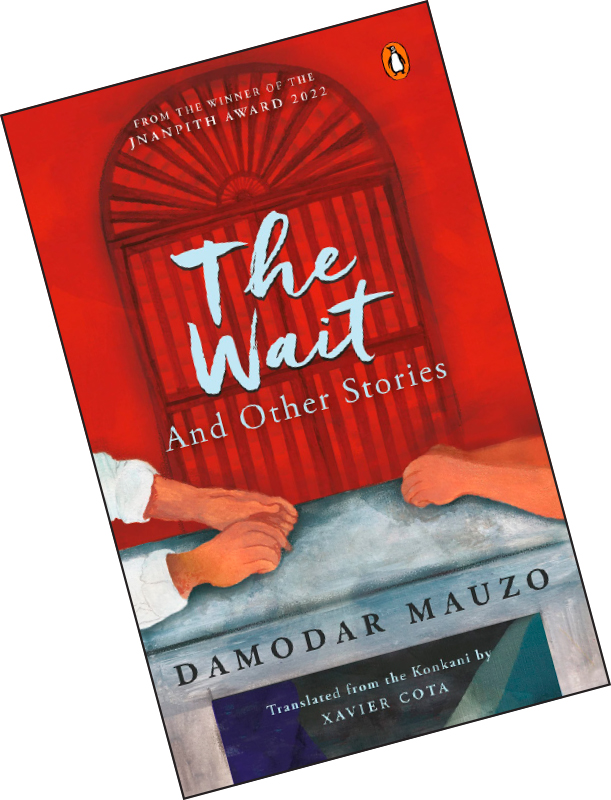

If you are looking for a quick read that’s easy yet mindful, pick up The Wait and Other Stories by Damodar Mauzo, translated from Konkani by Xavier Cota. Although the book had been bought a while ago, I studiously avoided reading reviews of it until I had finished reading it myself. I had, many years ago on a week-long visit to Goa, been introduced to Mauzo through his Sahitya Akademi Award-winning novel, Karmelin. Hence the excitement of self-discovery.

The path-breaking Karmelin, which I read in English translation by Vidya Pai, recounts the story of a woman who takes up a maid’s position with a rich family in the Gulf in order to escape from her tribulations at home and for possible financial security. Like a lot of translations, this one too was not ‘smooth’ reading in the way, for instance, Tomb of Sand (see last month’s Worldsworld) is. But the storytelling is gripping and the story a glorious examination of truth. When I read The Wait, there was an epiphany of sorts regarding translations. It felt like walking on a pebbly beach where the sound of water leaving the shore produces a tinkling sound. The comparison is, of course, with a sandy beach where the sound that dominates is the soft or loud whoosh of the waves.

To clarify: Tomb of Sand has been translated brilliantly; you never feel the burden of translation, it reads like an original. Here and there, however, some words and phrases have been used that an Indian speaker/writer of English would almost never use. Since a friend has borrowed my copy of the book, I cannot substantiate this with an example. You may have read or heard the phrase ‘in back’ in an ‘English’ book or in conversation with an American. Indians would probably say ‘in the back’. Or, to give you a more common example: ‘Can I have the check please’ as against ‘Can I have the bill please’. That is to say, translations, even the truest ones, invariably reflect the language of the translator. Hence the ‘English-ness’ of Tomb of Sand and the ‘Konkani-ness’ of Karmelin and The Wait. I will not try to explain further; I leave it to you to observe keenly the next time you read a translated work.

The Wait is a collection of 14 short stories, each quite different from the other, reflecting the pluralistic character of Goan/Indian society. In it you will meet all kinds of characters in all kinds of situations. You catch a glimpse of what lies beneath the surface and begin to understand the underlying social criticism in a gentle narrative. There’s a taxi driver who calls himself Yasin, Austin, Yatin, depending upon who he is driving at the time. There’s a little girl who suffers pangs of conscience because she shared a nonvegetarian burger with her vegetarian friend. There’s a ‘gentleman’ thief, and a man hung up on external beauty who cannot bear the deterioration of those attributes. We see attachment, cowardice, one-sided love, power games, daydreams and night dreams… reading these stories you understand that Mauzo is a keen observer of life and emotions, and we all know that life and emotions are a pretty complex business. The stories touch upon all of this in a seemingly simple way and leave you reflecting upon them long after the story has ended. In other words, the story in the book has ended, but the story in the life described continues. The references to current events only strengthen this notion.

So, who is Damodar Mauzo? He is the latest winner, the 57th, of India’s oldest and highest literary honour, the Jnanpith Award, for ‘outstanding contribution towards literature’, and only the second Konkani writer after Ravindra Kelekar to earn it. He lives in Majorda village, Goa, and has been writing for about 50 years. He says, ‘I think I am a writer because I am a good reader.’ Thanks to observations made by Mauzo in an interview with Arti Das published in Firstpost recently, I came to know that the Konkani script is mired in controversy. Valerian Rodriguez, in an August 2013 article in EPW, writes, ‘Konkani is a unique language. It is probably the only language in India which is written in five scripts — Roman, Nagari, Kannada, Persian-Arabic and Malayalam — with credible oral and written literature in each of them.’ In this connection, Mauzo says, ‘When we are speaking about the script, it usually gets associated with identity and then it gets political. The script is not identity, language is.’

Rodriguez points out that ‘For many Konkani lovers emotionally attached to the language, the script controversy endangers the impressive strides the language movement has made in the last fifty years, i.e., a separate political identity for Goa which was achieved in 1967; the recognition of Konkani by the Central Sahitya Akademi in 1975; the recognition of Konkani as the official language of administration for Goa in 1987; and the inclusion of Konkani in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution, which lists the major national languages, in 1992.’ Those interested in this issue, do please look up the article.

In the Firstpost interview, Mauzo says of his believable delineations of female characters, ‘I believe that within me there are my father and my mother. Also, I was more attached to my mother while growing up. Probably that’s why I may be in a better position to understand their situation.’ And about creativity and the growing threat to freedom of expression, he says, ‘I feel now that the responsibility of the writer is increased. Literature is also a reflection of the times we live in. A writer must ask questions, and raise issues, and for that, there is no need to be aggressive about it. One can do it subtly and more responsibly. I hope that in times to come the people who are opposing such things will realise that was nothing wrong with it.’

This little extract from ‘Burger’ reveals much of Mauzo’s genius:

‘…Daddy returned home for lunch, it being a half-day. Mummy immediately told him, “Ever since she gave beef to her Hindu friend, Irene has been moping.”

‘Daddy laughed. “Never mind, Irene. Since you have defiled her, now we’ll have to find her a nice Catholic boy and marry her off!”

‘Irene could not fathom whether her father was serious or just pulling her leg. She thought of asking him directly but got up instead and silently went inside.

‘So she had defiled Sharmila. But what she actually done? The word “defile” has a stink to it. To say that she had defiled her meant that she had spoiled her. Daddy said we had to find a Catholic groom and marry her off. As if we can do this! Marriage has to be a question of one’s own choice. Daddy himself says that the days of parents searching for partners for their girls are over. And in books, too, we read the same thing. Poor Sharmila! Irene hoped nothing bad would happen to her.’

The world of The Wait is multicultural, multireligious, multilingual. It is filled with events and flavoured with a gamut of emotions. It’s a real world of sounds, smells, tastes and images. I savoured every one of the stories with delight. I invite you to do the same. You will not be disappointed.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist