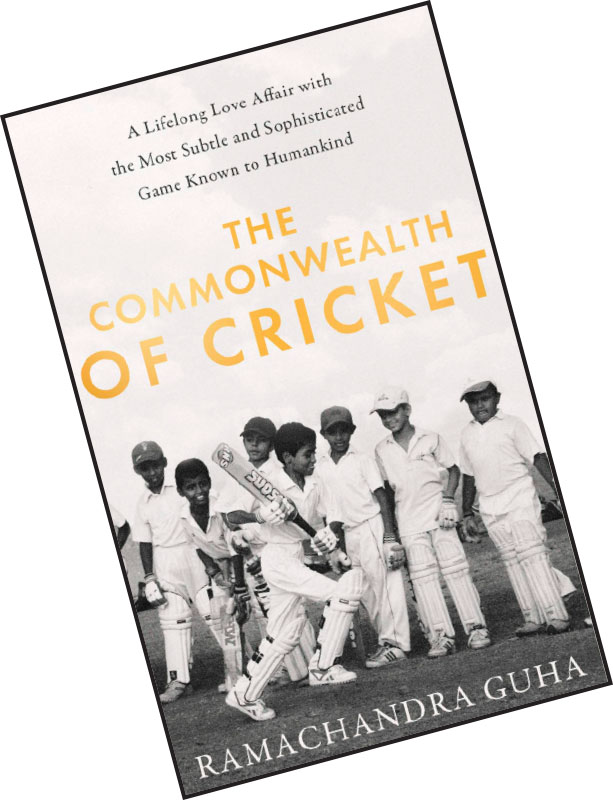

In the backdrop of the Indian cricket team winning the recent Test series in Australia, thus lifting spirits, it is logical to showcase a cricket-related book. I have picked The Commonwealth of Cricket by Ramachandra Guha, a personal memoir by a historian with a passion for the game. As the author description on the jacket flap says, ‘He says he writes on history for a living; and on cricket to live.’ A few years ago, I had read his A Corner of a Foreign Field: The Indian History of a British Sport practically at one go. Constructed on a foundation of solid research, sound argument and felicitous writing, that’s a book anyone can, should, read: you don’t need to be a cricket aficionado. Just as you don’t have to be a rifle shooter to read A Shot at History, the story of Abhinav Bindra brilliantly written by journalist Rohit Brijnath.

The Commonwealth of Cricket, however, requires some degree of familiarity and interest in the game because much of it is about Guha’s own ‘real action’ engagement with the game as a school boy and university student.

Those who have read him know that he takes the fight to the front. ‘I am by nature and instinct an anti-Establishment man,’ he writes in this book. ‘I left the academy 30 years ago, and have since had no allegiance to a formal institution. I could not cope with working in a university, and would have found it impossible to work in a newspaper or corporate office. I have never been a member of a political party. The Friends Union Cricket Club is an exception to this rule, but there is nothing formal about this lone institution to which I belong. The FUCC has no office, owns no property, and has no paid employees.’

You may ask what the connection is between cricket, politics, twitter and being anti-establishment. Guha is the connection. Woven into this book which is on the one hand a journey down memory lane with all the fine print intact, including who scored how many runs and who took how many wickets, is a ringside view of the games people play when they play games. But be warned: it takes patience to get to those bits.

Be prepared for juicy stories, facts and all. The outside stories concern Guha’s personal cricketing on-field achievements, or rather, non-achievements, by his own admission. The inside stories are analytical, insightful, and definitely distressing, even though it’s no secret that sporting organisations in India are rife with nepotism and corruption. There are a few brave ones still standing, but these are few, too few. Guha’s person of such standing is the redoubtable left-arm spinner Bishen Singh Bedi whom he refers to several times in the book. The author revives memories of several moments and personalities in the cricketing history of this game as he revisits different eras and the prodigious talent and prowess of cricketers from his club, state, country and other parts of the world.

One of the most interesting bits of cricket’s political history that Guha sheds light on relates to the Lodha Committee.

While reading, I experienced several moments of déjà vu. I remember the last time the maverick Pakistani cricketer Javed Miandad appeared for Pakistan in an ODI; it was a match against India, a World Cup fixture in Bengaluru. The image of him walking off the field after he got out, turning back every now and then to look at the pitch as if to imprint the picture in his mind… that television image remains vivid in my mind. I remember standing up to applaud him in my living room, not because he was my favourite but because he had dared so much. Guha refers to this very moment in the book as he recalls that match: ‘Nine an over were required when he was run out by a direct hit. When he walked off the ground I stood up to applaud him. “Why are you clapping?” asked an obnoxious fellow from a row behind. “You should clap too,” I answered, recklessly. “This is the last time any of us will see him bat.” “Thank God I shall never see the bastard again,” came the reply. How did I think that an uncertain internationalism would be equal to a single-minded patriotism?’

One of the most interesting bits of cricket’s political history that Guha sheds light on relates to the Lodha Committee. In the wake of several public interest litigations after the match-fixing scandals and instances of conflict of interest exacerbated by the IPL, the Supreme Court set up a three-man committee headed by a former chief justice, R M Lodha to clean up Indian cricket. This committee in turn set up a Committee of Administrators (COA) and invited the author as a member. Guha recounts the experience of engaging with Rahul Dravid on the question of conflict of interest, which is insightful. He refers to an email he wrote to Dravid who, at the time, was coaching the India ‘A’ team and during the IPL was coach of the Delhi Daredevils, and the resulting stand-off between the two. Luckily this was bridged thanks to the cricketer taking on board some good advice from a mutual friend, the former England captain Mike Brearley.

I couldn’t cope with working in a university, and would have found it impossible to work in a newspaper or corporate office. I’ve never been a member of a political party.

— Ramachandra Guha

Individuals, institutions, everything comes under the glare of Guha’s keen study and astute analysis — and this includes himself. He describes with candour the less than cordial nature of his relationship with the original Little Master, Sunil Gavaskar, even as he holds nothing back in praising Sunny’s remarkable achievements on the playing field. The tension between them had a lot to do with the questions Guha raised as a member of the COA.

He also makes bold to spell out what many, at the time, may have thought but did not voice. A former cricket captain, Vijay Merchant, had once famously said one should quit at the right time, when people ask why and not why not. ‘He stayed on, and on,’ Guha says of SachinTendulkar, and wishes that ‘Tendulkar had taken his cues from Merchant and Gavaskar instead. It was not just that he kept going beyond his prime, but that in his (as it were) cricketing dotage he took the cricketing public for granted.’

There’s plenty to enjoy and assimilate in The Commonwealth of Cricket, among them some quirks such as lists of Guha’s dream teams, from a Karnataka XI to an eleven of Indian cricketers he has shaken hands with, to an eleven of his favourite Pakistani cricketers he has seen play, to a similar eleven comprising Indian players, to a joint All-Time Indo-Pak XI. There’s just one regret though: I grew up in the small industrial town of Durgapur in West Bengal. Come cricket season (or Davis Cup tennis) my father, who had been a keen cricketer in his college days in Coimbatore, would assign me the task of listening to the radio commentary and relaying to him all that had happened when he returned from work. Perhaps that’s what got me interested in sport, and cricket and tennis in particular. I wish my father was alive to read this book. He would have loved it.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist.