I was a mischievous child growing up. I often found myself in the master-in-charge or the principal’s office in all the schools I attended, whether it was for climbing up onto the classroom roof to escape classes, flinging books out of the window to see how far they would fly; the list is never-ending. My mother would be exasperated but Dada found them amusing.

On the rare occasion that Dada accompanied my mother to school to rescue me, the principals would be shocked to know that I was the grandson of “the” man pioneering the cooperative movement and ushering India as the world’s milk Mecca! Dada would often endearingly call me mandan in Malayalam, meaning silly fellow. His philosophy was simple, “One should never break a child’s spirit.”

My grandparents would visit my mother and I in Chennai whenever possible, which was pretty often. Usually on the weekends. Their go-to hotel was the Taj Coromandel; Dada would ask me to bring a couple of my friends for an afternoon swim in the pool, followed by a snack. My friends loved chatting with my grandparents as also the high tea. Dada would sit on the edge of the pool watching us like a hawk, trumpeting instructions, “kick this way”, etc. My grandmother would be giggling, I supposed at my bad technique. Only much later she told me that Dada did not know how to swim! Neither did he like water at all.

My friends and I were eternally cycling as it was our newfound skill at 8. One early morning as there was no traffic, we managed to navigate the main roads to reach the hotel near our home where my grandparents were staying. The doorman rang my grandfather to inform him; within minutes Dada was down and rushed through the lobby to everyone’s surprise, to the porch in his dressing gown, hauling us up the stairs to the room. Dada was furious with us for not informing anyone of our adventure and also forbade us never to take our cycles out of the house compound. Once he had cooled down, he treated us to a sumptuous breakfast. He was impressed by our expedition but kept a stern face in front of my grandmother.

I remember him standing up to greet a woman, be it a friend or a close relative. He was a chivalrous and thorough gentleman and never forgot his old-fashioned manners right to the very end.

Once I had to go out for lunch and as my mother was out, I asked Dada for some money and he gave me a ₹50 note from his wallet. I asked for more as I had three other friends. He gingerly fished out three crisp ₹100 notes from a secret hideout in his wallet and handed them out very reluctantly. When I returned after a few hours and returned the money, he asked if I had eaten lunch. I happily told him that my three friends, all girls had treated me. He was horrified, and said that I should always pay for meals and not allow girls to pay bills. I tried, unsuccessfully, to explain to him about gender equity, but totally unconvinced, he said that I should respect, cherish and treat women with great regard.

I remember him standing up to greet a woman, be it a friend or a close relative. He was a chivalrous and thorough gentleman and never forgot his old-fashioned manners right to the very end!

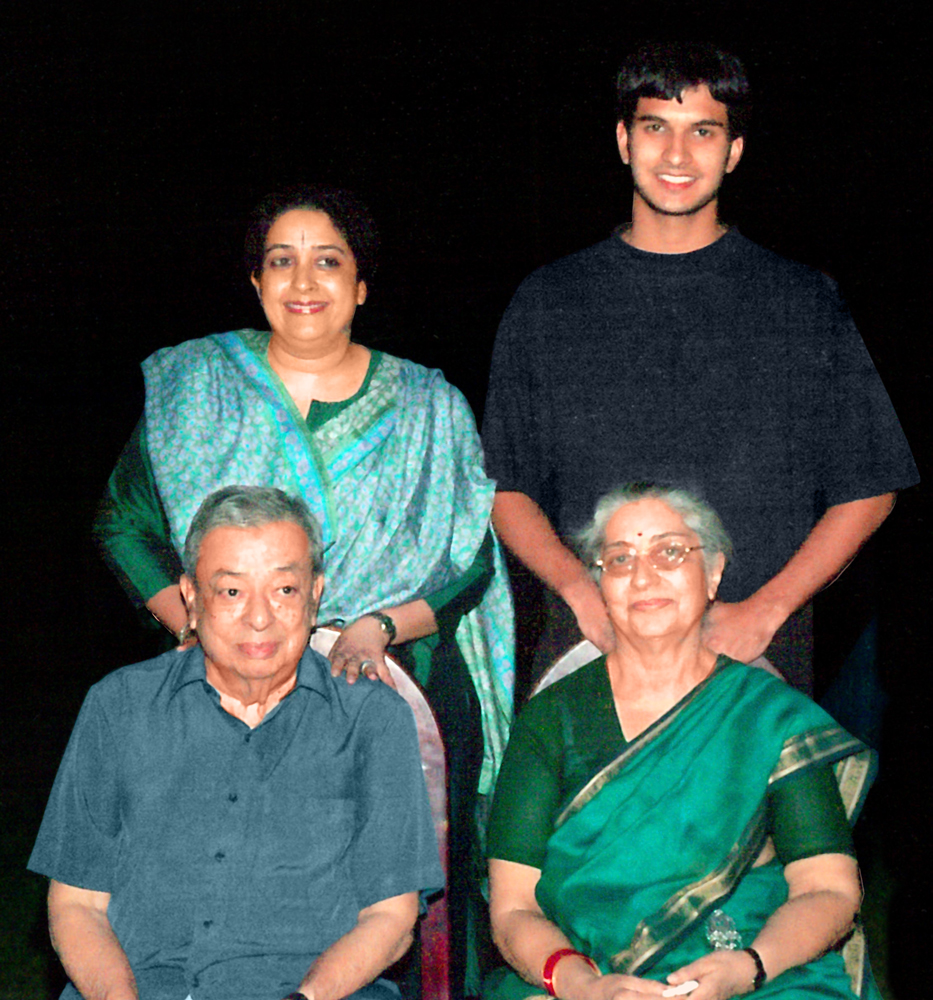

Nirmala is Verghese Kurien’s daughter and Siddharth is his grandson

The quintessential milkman of India

Nirmala Kurien

Armed with an MSc in US, Verghese Kurien started his working life soon after India gained independence. The noblest task in those days was to contribute towards building India of our dreams… a nation where people would be free from hunger and poverty. A nation that would eventually be counted among the foremost nations. He never intended to serve the nation’s farmers but a series of events put him at Anand, Gujarat. He chose to work for a fledgling cooperative instead of pursuing a career in metallurgy or nuclear physics.

‘Father of the White Revolution’ and the ‘Milkman of India’, Kurien was a social entrepreneur whose “billion-litre idea”, Operation Flood, made dairying India’s largest self-sustaining industry.

In 1964, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri visited Anand, spent a night in a village and talked to farmers about their cooperative. On returning to Delhi, he requested Kurien to set up the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB). Kurien pioneered the Anand model of dairy cooperatives and replicated it nationwide, where no milk from a farmer was refused. He believed in empowering the farmers, never doubted their ability to work hard and produce more if there was a market. For the small, marginal and landless farmers, dairying is not only a source of nutrition, but also a source of supplementary income and security. Much of the work involved in milk production, be it feeding, day-to-day management, health care etc were traditionally handled by women, comprising half the population.

This had a far-reaching impact on the cause of empowering women. As the world was reeling under the impact of Covid, job avenues decreased, the income from such milk production activities became critical for many families, and enhanced the important role women played in their families.

Kurien’s legacy through the higher consumption of milk in India is an increase in average height of an Indian just in one generation. Thousands of dairy cooperatives and millions of members experienced grassroots democracy and he empowered millions of rural Indians!