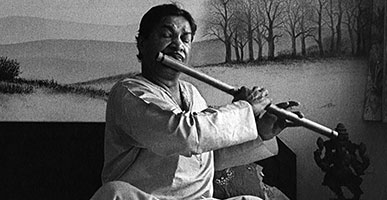

Flute maestro Hariprasad Chaurasia seems a genetic oddity — a consummate and world renowned musician born to a wrestler father and a homemaker mother who never went to school. The parents had no artistic pretensions, the mother died young, when the boy was barely four, and the father dreamt of his sons becoming wrestlers and earning name, wealth and fame through exploits in the akhada. Hariprasad, the youngest, born on July 1, 1938 at Allahabad, however, discovered the joy of music even as a child, and yearned to achieve excellence in the field. Despite — or perhaps because of — Chedilal Pehelwan’s towering paternal presence, he also developed a distaste for wrestling, though he faithfully did everything to stay strong and fit as demanded of an aspiring wrestler. He swam, ran, exercised — and, naturally, ate well.

Parental disapproval aside, little Hari joined the chorus of devotional singing in a nearby temple, encouraged by the family’s neighbours and the temple priests who loved his sweet voice. Not long afterwards, he serendipitously fell under the spell of the bamboo flute, when he followed a street child playing a plaintive tune on his humble bansuri. Hari actually stole the flute from his pied piper, if we are to believe the lore surrounding the artist.

Hariprasad earned a college degree in arts and the starry-eyed lad once ran away from home to seek his fortune in Bombay cinema.

He did take music lessons even if the idea met with his father’s disfavour — and perhaps unbeknown to him. His first music teacher was Pandit Raja Ram, a reputed dhrupadiya from the neighbourhood. Dhrupad must have posed considerable challenges to the child who only knew simple tunes from the devotional oeuvre.

Hari also benefited from his association with an ayurvedic doctor and neighbour Kailashnath Chaturvedi, whose family had a keen but amateur interest in music. At the Chaturvedi home, he regularly joined in the impromptu practice sessions in which father and two sons sang and played the harmonium and the tabla.

Soon Hariprasad was singing solo at the temple. According to Chaurasia’s biographer Uma Vasudev, (Romance of the Bamboo Reed, Shubhi, 2005) many of Chedilal’s neighbours entered into “a conspiracy of silence” hiding Hari’s musical exploits from the father’s eyes and ears, as they knew he would not approve, bent as he was on a wrestling career for his son, especially after a mysterious illness claimed the life of eldest son Shivprasad at 17.

Hariprasad earned a college degree in the arts stream though he had been impetuous and starry-eyed enough once to run away from home and wrestling, his pet hate, to seek his fortune in Bombay cinema. He and a friend knocked on the doors of film studios in vain before some kindly soul gave them some sage advice and sent them back home. Father forgave son and all was well.

Chedilal was smart enough to enrol Hari in a typewriting class. Armed with a BA degree and exceptional typing speed, Hari found a job as a typist first in the office of the Praja Socialist Party, and later at the Allahabad Milling Company, which offered him better pay. All seemed well, with Hariprasad seemingly reconciled to his regular job, until one day he happened to listen to a flute concert on the radio by AIR artist Pandit Bholanath which drew him back into the magic world of music. He walked into the AIR office seeking an appointment with Bholanath. He impressed him enough for him to eventually accept him as his shagird. Passing his audition test, Hariprasad was accepted as a Grade ‘B’ AIR artist, creditable for someone of his youth. By this time, Hariprasad was well immersed in music, practising during his lunch hour and after the day’s work. The secret of his musical exploits was finally revealed to Chedilal when his early concert appearances were reviewed in the local press. Pleased with his son’s new found success in music, firmly grounded as it was in steady employment, the pehelwan relented enough to allow Hari a break from wrestling.

Allahabad was now a prominent centre of Hindustani classical music, thanks largely to music festivals and conferences conducted under the aegis of the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya founded by Vishnu Digambar Paluskar. Hari attended these festivals and soaked in some of the great music on offer from the likes of Amir Khan and D V Paluskar, though to his regret, he never had the opportunity of attending a flute concert by Pannalal Ghosh, arguably the greatest exponent of the art. According to musician-journalist Sivapriya Krishnan writing in the performing arts monthly Sruti, Chaurasia made bold to meet eminent musician and guru Alauddin Khan in his hotel room during one of these conferences, and he advised him to enrol himself in his famous gurukul at Maihar to learn from his daughter Annapurna Devi, the surbahar expert. (As quoted in Sruti magazine, “Such a migration from Allahabad to Maihar was then a dream too far for the young man but Allauddin Khan’s invitation remained permanently etched in Hariprasad’s heart and mind, and he pursued his ambition relentlessly while establishing himself as a flautist contributing to the song and dance routines of Hindi cinema in the 1960s. Annapurna Devi was then leading the life of a recluse after the breakup of her marriage to sitar maestro Ravi Shankar. Chaurasia just refused to take no for an answer, and besieged her house with his never ending attempts to win her approval. When the nod came, it was accompanied by stern demands: to unlearn a great deal of what he knew before learning anew; to play with greater sustain rather than in staccato phrases; to go deeper into individual ragas rather than indulge in virtuosity. Bizarrely, Hariprasad even switched to playing left-handed as a token of his reverence to his guru. Thus embracing the Maihar gharana as he did, Chaurasia also added several new dimensions to bansuri music, incorporating both the vocal (gayaki) and the instrumental (gatkari) styles of flute playing, revolutionizing the way the instrument was treated by the artist and received by the audience.”)

His typing and stenography skills earning him a job in the government’s district planning office, Hariprasad was able to devote all his spare time on music practice, now with his father’s grudging approval. As a regular performer for AIR Allahabad, he jumped at an opportunity provided by programme executive Shantimaya Ghosh to apply for a permanent job in AIR at either Lucknow or Cuttack. Chaurasia struck gold, though he did not know it at the time, when posted to Cuttack, his second choice. The lure of a steady government job helped Chedilal allow Hari to leave hometown Allahabad.

The tipping point of Chaurasia’s music career was provided by AIR Cuttack’s station director, P V Krishnamoorthy (PVK), who was also a talented music composer.

Thus began an unusual association, a mentor-mentee relationship rarely seen in the annals of Indian classical music. Chaurasia had quit AIR decades earlier, but both he and PVK retained their mutual respect and affection even decades after they first met, as was evident at PVK’s 90th birthday celebrations at Chennai, when Chaurasia paid rich encomiums to his guardian angel. He also promised to repeat the honours at his 100th, but PVK passed away three short of his century in 2019.

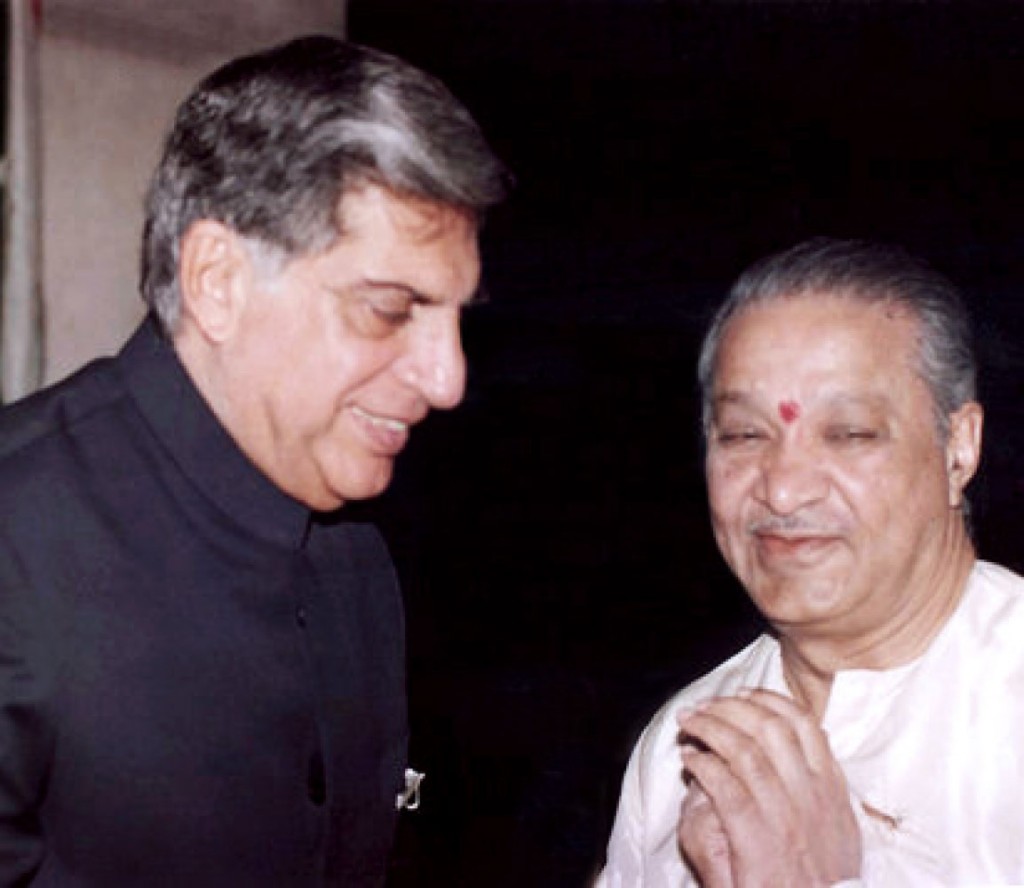

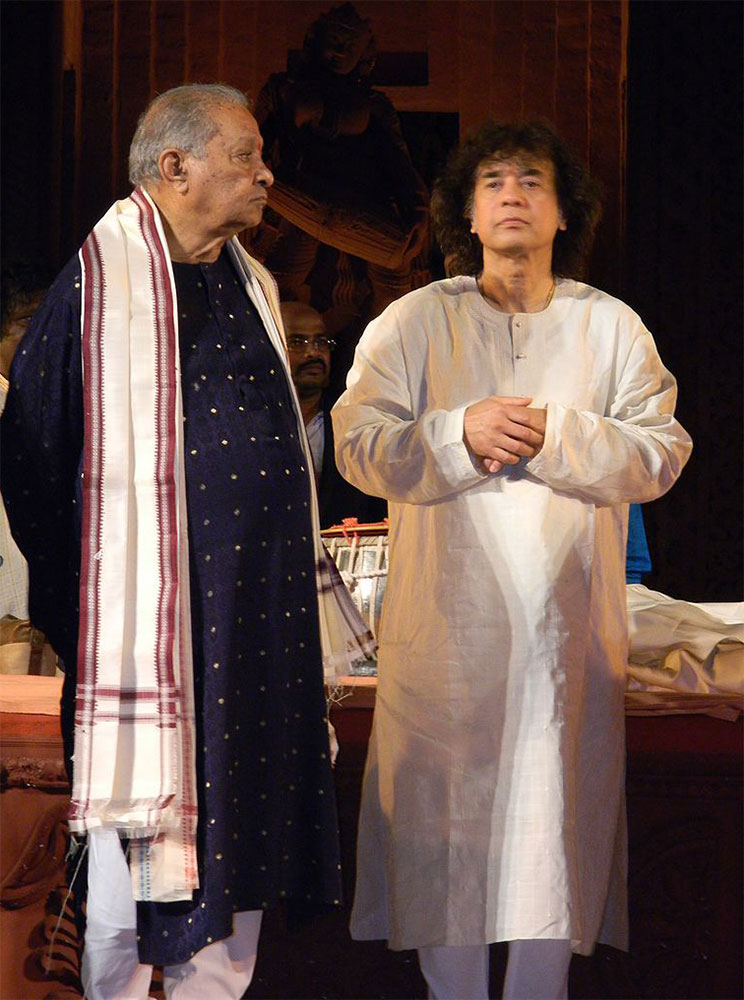

Hariprasad Chaurasia has always admired and respected fellow musicians, be they his juniors, peers or seniors.

To many listeners of Hindustani music in the 1960s, the sitar and sarod of the likes of Ravi Shankar, Nikhil Banerjee and Ali Akbar Khan had been an enchanting introduction to those instruments, while such flautists as Pannalal Ghosh presented rarer listening opportunities through recordings. A new kind of magic was on offer when a bestselling LP titled Call of the Valley captured the imagination of many young aficionados still on the cusp of transiting from film music to classical music. The record featured three brilliant instrumentalists in Chaurasia (flute), Shivkumar Sharma (santoor) and Brij Bhushan Kabra (guitar). Chaurasia’s flute presented a haunting counterpoint to the more stirring virtuosity of the two string instruments. The raga Bhoop in that record has perhaps seldom been equalled by a wind instrument. Chaurasia was at his creative best besides being extremely strong in his blowing prowess and the myriad new technical variations he was to make his own forever afterwards. The folksy raga Pahadi acquires the most classical contours in his hands as he breathes extraordinary nuances into it.

He and his colleagues Zakir Hussain, Shivkumar Sharma and Amjad Ali Khan swept Hyderabad with their youthful freshness and the gift of their legacy when they performed there circa 1972–73. Shiv-Hari became a successful duo on the concert platform and in record labels in India and abroad. They also worked together as music directors in the Hindi film industry, notably in movies like Silsila and Lamhe, before eventually parting as friends to strengthen their individual identities as outstanding musicians.

A new kind of magic was on offer when an LP titled Call of the Valley captured the imagination of many aficionados on the cusp of film and classical music.

Once he “arrived” as a leading artist, Chaurasia came to be known for his infectious humour and bonhomie through the decades. At Kalakshetra, Chennai, in 1982 or thereabouts, he gave such a mesmerising performance that one critic hailed him as a modern day Krishna who cast a spell on a hall full of gopis in the Brindavan that was Kalakshetra that evening. There was a magical raga Kedar on offer if memory serves one right, and when a young female fan expressed her appreciation for it, the flautist shot back with a glint in his eye, “You know, I played it especially for you”. He had been equally disarming before the concert, when another fan asked him to play the raga Hemant. “I don’t know that raga yet. I’ll go back and learn it from my guru before my next concert here,” he said in all earnestness. Another sample of his wit: Midway through a concert, he announces “Interval, fortyfive minutes.” When the audience lets out a collective sigh, he explains: “Interval for tea, five minutes.”

For someone of such humility, Chaurasia boasts a considerable repertoire of ragas including some of south Indian origin, Charukesi and Hamsadhwani, for instance. His mastery of morning ragas is complete. After all he played them countless times in films to herald a new dawn; only we didn’t know that those beautiful scenes amidst mountains and brooks were often announced by such a distinguished musician.

Hariprasad Chaurasia has always admired and respected fellow musicians, be they his juniors, peers or seniors. And he continues to honour them with dedication through his Vrindaban Gurukul, the home of soirees he curates to this day at his Mumbai home, taking Hindustani music to true lovers of the art in an intimate setting. Its Bhubaneswar branch is his way of saying ‘thank you’ to Odisha, the state that through AIR Cuttack and PVK gave him his major break. His musical journey has probably taken its final turn — a serene and profound bend.

The writer is an author and former editor of Sruti magazine.