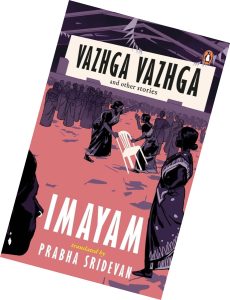

It’s been a season of elections all round — with interesting results — in India, the UK, France, and Iran, for instance, and the season is upcoming in the US. It was serendipitous that I had occasion to read the Tamil writer Imayam, translated by Prabha Sridevan. While the latter is a former judge of the Madras High Court, Imayam is known for incisive writing that is inspired by the socio-political environment. In fact, he says, literary texts cannot escape their political reality, and this premise underlines Vazhga Vazhga, a compilation of one novella and two short stories.

The title means ‘long live, long live,’ and in itself points to a likely political scenario, which is exactly what the novella is about. Venkatesa Perumal, a party worker, is tasked with rounding up crowds for a political rally to be addressed by the party leader, whose posters are displayed everywhere. As one individual says to Perumal, ‘You put up posters and cut-outs depicting her as Kanchi Kamakshi, Madurai Meenakshi, Samayapuram Mariamman, Velankanni Matha and even Mother Tamil, thamizhthai. Isn’t it too much?’ It is this ‘too much’ of politics, in this case, Dravidian politics, that features in the novella that makes no effort to camouflage either its references or its intention. This, along with a narrative that carries the reader along almost in real time, gives the story a distinctive Tamil flavour that is effective and affecting. ‘Your thalaivi, your leader, she treats everyone in her party worse than a dog. How can you be in that party?’ someone asks. Perumal knows he is being deliberately provoked, so he responds, ‘Even if she treated them like that, she gives them posts like MLA, MP and minister.’ Quid pro quo?!

No matter how popular a leader, it’s an open secret that much of the crowds at political rallies, especially during elections, are forcibly transported to rally venues through the exercise of ‘bribery and corruption’ as some old-timers are wont to say. Meaning, for a few rupees with packed lunch of a mixed rice and a bottle of water thrown in. Sometimes, if they are very fortunate, non-veg too. Vazhga Vazhga looks at the story of a political rally from the point of view of the patient denizens who wait and wait and wait in unforgiving weather for the arrival of the leader, who often is not even their leader. Imayam describes the scenes vividly. For instance, ‘Every woman there, without exception, was fanning herself with either the cap or her sari. Being in the crowd made them all feel the heat more, but there was nowhere they could go from the crowd or stand for shade. To accommodate the crowd, all the trees in the 400–500 acres of land expanse had been cut. There was not a tree, plant or creeper as far as the eye could see. All that could be seen were the party flags, festoons, cut-outs and digital banners.’ Perfect.

While we are aware of how long the wait could be, it is possible we don’t know or have not thought about what the wait entails. Imayam tells us, in great and exacting detail. The sun is burning down on them, they are thirsty, they need to relieve themselves, they have concerns at home… How Imayam pulls off a story that seems not to move while it actually ploughs relentlessly forward is a tribute to his gift of storytelling.

The two short stories in this collection are completely different from the novella and from each other. ‘Tiruneeru Sami’ pits against each other a woman from North India married to a South Indian in what appears to be a classic cliché. But it is not. Again, it is the keen observance of life and relationships by the author that transforms the story from the obvious to make it resonate. It exemplifies the local-global binary at a personal level while at the same time positing universal truths. The narrative style, too, is subtly different from the novella in that the telling is more smooth, almost seamless. What is the couple locking horns about? Where to get the tonsure ceremony of their two small children done. Annamalai wants to get it done at his family’s place of worship dedicated to a saint, Tiruneeru Sami, in Tamil Nadu. Wife Varsha strenuously objects to this. Imayam chooses not to provide a resolution to this ‘dilemma’; he offers a study in which, once again, we can find ourselves reflected.

At one point in the story, Varsha’s brother Alok enters the fray. He sits down to listen to what Annamalai has to say and appears to be getting convinced gradually. When he tries to advocate for his brother-in-law, Varsha responds that it is ‘A story without a head or tail.’

‘I really believe Annamalai will not lie to us,’ Alok says. To which Varsha replies, ‘He will not tell lies, but he will tell us stories.’ Not lies but stories! The sentence lands like a punch in the solar plexus. Think about it: this column, this magazine, we human beings… It is all about stories, we are all about stories, our lives are stories. Anything we might say to each other could be seen as stories, anecdotes, short stories, novellas, novels, epics…

The other story is completely different. It’s a mythological tale, ‘Samban, Son of Krishna — An Untold Tale’. I did not know this story prior to reading Imayam, and am in no position to comment on perspective, let alone details. Imayam’s version speaks of Samban, Krishna’s son by Jambavati, who is cursed by the sage Durvasa for having been rude to him. Samban loses the pleasure-filled life of an indolent prince and has to leave the palace. He goes through trials and tribulations, has encounters, and eventually is afflicted with leprosy. He is cured, and helps cure others, by worshipping the sun. Imayam narrates how he deals with his curse and what he learns along the way, about himself and his life. With great profundity, he tells Narada, ‘…I realized that this life is as transient as a lamp in a hurricane. Human life is the smallest of trifles. I had a father and a mother. I had elephants, armies, troops, palaces and boundless wealth. But when I came here, I came alone, the solitary me. The disease alone accompanied me.’ Yet, despite the heavily loaded cast of characters comprising Narada, Durvasa, Krishna, Suryadeva, the story is replete with socio-political messages, in keeping with Imayam’s belief that writers can never be apolitical.

And in the Indian context, if politics comes, can religion be far behind? The short stories showcase in their own way the place of ritual, faith, belief and the relationship between religion and science in our minds. Was this deliberate? Or is it intrinsic? That’s for the reader to decide. For now, I have launched into another collection of short stories, this time by well-known writers in Hindi, translated by the well-established Jai Ratan. What kind of experiences will these stories offer? What kind of worlds will these stories showcase?

A word about the translation of Vazhga Vazhga would be relevant here: while the short stories work well, the novella occasionally seems to sound literal, sometimes forced. But on the whole, it evokes the Tamil world without pretensions, and that’s a feat alright. The stage is set to engage with the ‘Hindi’ worldview.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist