On the gender front, anybody who visited Afghanistan in 2005, as I did, and I suspect nothing much has changed, is bound to come away with a heavy heart. The Taliban had left the scene in November 2001, but they totally destroyed girls’ education and women’s confidence by ensuring that the “second sex” was always confined to the house. I met Parveen, an activist of the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA), which had put up such a valiant fight for the rights of women during the Taliban era, and even earlier. She told me that “even though the situation on the gender front has improved compared to the Taliban era, much more needed to be done”.

She had left the country during the Taliban years and worked for RAWA from Peshawar in Pakistan, and was rather sceptical about the “liberal stance” taken by the then Hamid Karzai government on the gender front. “This is more due to pressure from the US. We find most people in the administration, including some of the top ministers in the government, fundamentalist at heart. Right now, they are just paying lip service to women’s emancipation to please the Americans.”

What she said next rang so true to all countries, including ours, which often pay only lip service to the gender cause. “The Afghan woman is most persecuted within her own home. The father, the husband, the brother… these are the people who torture her the most; in many homes there is a lot of domestic violence, the women are forced to wear the burqa and girls are not allowed to go to school or college or to work.” RAWA activists accused the government of packing the country’s top judiciary with male chauvinists who had no qualms in going on record that a woman can never be equal to a man!

I ask a “westerner” — The World Bank’s country chief in Afghanistan, Jean Mazurelle — to comment on the gender situation and the role of the international community in improving women’s status in Afghanistan. He feels this is an area where the Western aid organisations would have to tread cautiously. For instance, a “white” man telling the Afghan woman to be emancipated and go out without the burqa would be a disaster. “If we do that we could be perceived as Westerners imposing Western values on the Afghan women. We have to be very careful not to create any backlash from people who say the Westerners are trying to unveil our women.”

But the Frenchman then went on to add something which had me beaming. “But Indian women, who are here in good numbers and various capacities, representing the voluntary sector and even several UN organisations, are much better placed to make a difference on this front.” All praise for the role India was playing in the reconstruction of Afghanistan, he said that many of his female colleagues from World Bank in Delhi either visited or were working in Afghanistan.

India has always been a friend and has never coveted anything that belongs to us or done anything to hurt Afghanistan’s interests.

– Haji Abdul Hakeem, a carpet shopowner

“In their interaction with the Afghans, they are respectful of the environment here, but at the same time they’re able to convince them quite a bit on gender issues.” He added that he would be delighted to “see the Afghans looking at India’s development path rather than that of Iran or Pakistan.”

India, an admired neighbour

Forget what Mazurelle is saying about India and its influence, in most of the Islamic world, be it an Iraq or a Turkey, India is looked upon with respect, admiration and even love. Indians visiting Afghanistan were in for a pleasant surprise. Afghans just love India and Indians; not only Indian films and actors Shah Rukh Khan and Aishwarya Rai, but also the country’s record in economic development, education, healthcare and promotion of a liberal ethos.

The then Indian ambassador to Afghanistan Rakesh Sood pointed out that the GoI had put in some $600 million from its aid budget to help the reconstruction effort in Afghanistan, and this was visible all over. As he pointed out, India was one of the first countries to get involved in infrastructure building, “and we worked all across the country at a time many donors were hesitant to go out of Kabul owing to the security situation.”

So whether it was the rebuilding of the $90 million Salma Hydel Project; the laying of hundreds of km of roads and power transmission lines; the setting up of Afghanistan’s first cold storage plant in Kandahar so that this fruit bowl could process and export its produce; the reconstruction of the famous Habibia School in Kabul where Karzai was once a student; the reconstruction of the 250-bed Indira Gandhi Institute of Child Health, the only paediatric hospital in Kabul, at a cost of $3 million; or the training of teachers and Afghan government staff, Indian presence was very visible.

The Afghan woman is most persecuted within her own home. The father, the husband, the brother… these are the people who torture her the most.

Interestingly enough, I found, and for obvious reasons, Afghanistan’s neighbours Iran and Pakistan were looked upon with suspicion, if not hatred. But India was admired for a host of reasons. At the bustling Chicken Street, one of Kabul’s most favourite shopping areas, I talked to Haji Abdul Hakeem, who owned a carpet shop here. An ardent fan of India, he said: “Look at your education system; you turn out such fine students from your institutions.”

He had a very interesting analogy to compare India with other countries when it came to Afghanistan’s foreign relations with other countries. “As you know, for long years we have had a troubled history, with so much violence and bloodshed. Afghanistan has been like a muddy river, and so many countries, whether it is the mighty United States, Soviet Union, Iran, or Pakistan, all of them have tried to fish in our troubled waters and exploit us. Except India. India has always been a friend and has never coveted anything that belongs to us or done anything to hurt Afghanistan’s interests.”

So what would he like India to do towards the future development of the ravaged nation, I asked him. “Nothing much for a country like yours. Your education system is among the best in the world. The best help India can give Afghanistan is to pick up our children, say 500 boys and girls — from Kabul, Mazar, Kandahar, Bamiyan and so on — and give them education in India. When they return as fine scholars and professionals, they will have the potential to reshape the future of our country.”

Value of Indian doctors

If Indian education was held at a premium here, Indian doctors and medicines were considered priceless. On our flight from Delhi to Kabul, there were at least two medical teams bound for Afghanistan. While the private players, particularly from the heart care institutions, were scouting for business, the GoI was sending doctors from the central government health services to put in a stint in Afghanistan, where the healthcare services had been devastated by the long-raging war.

Indian ambassador Sood told me that five Indian medical teams were working in hot spots such as Kandahar and Mazar-e-Sharif. When asked if security was not a concern, he said: “People just love Indian doctors and trust them and their judgment implicitly. We find that there is great faith in both Indian diagnostic skills and Indian medicine, because there is a lot of adulterated medicine in the markets here. The general perception is that to get well one must go to Indian doctors and take medicines from them. Sometimes when medical supplies run out, people will wait for a day or two for medicines from India rather than buy from the local market.”

Vile destruction of Heritage Buddhas

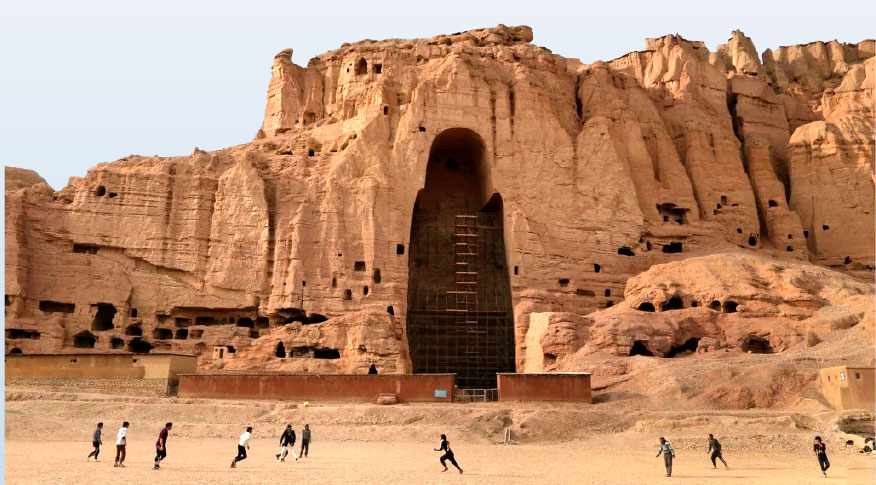

However much one had read about the heinous act of the Taliban in destroying the ancient 6th century giant Buddha statues in the Bamiyan valley bang in the heart of the Hindu Kush region, visiting the massive Bamiyan cliff where these majestic Buddhas once stood, and where we could now only see the huge holes in the caves, was nothing short of a stomach-churning experience. In those horrid hollow spaces once rested magnificent Buddha statues, the bigger one 55 metres tall and the smaller 35 metres, resplendent in red and blue attire, adorned with glittering ornaments and surrounded by colourful paintings.

Sometimes when medical supplies run out, people will wait for a day or two for medicines from India rather than buy from the local market.

– Rakesh Sood, Indian Ambassador to Afghanistan

The Taliban, after seizing power at Mazar-e-Sharif and the area around this location around 1998-end, blew hot and cold between 1999 and 2001 about destroying these statues which the savages declared “un-Islamic”, despite UNESCO having declared it a world heritage site. History says that every year Buddhist pilgrims from within Afghanistan and overseas would come here annually and offer prayers and the most famous cultural landmark of this region saw a festival atmosphere.

In July 1999, Taliban chief Mullah Mohammed Omar decided to preserve the Bamiyan Buddhas saying that as the statues were no longer worshipped, this site could be a potential money spinner as an international tourist spot in the future.

But in Feb 2001, the Taliban did an about turn and decided to destroy the statues causing an international uproar. All the 54 heads of the OIC (Organisation of the Islamic Cooperation) countries condemned this decision at a meet called by UNESCO. Both India and Japan offered to move the statues to their respective countries at their cost; Japan even offered to “cover” the statues and give additional money to the Taliban as compensation. Even Pakistan President Pervez Musharraf wrote to the Taliban requesting them against “this unIslamic act”. But nothing worked and the Buddhas were blown to smithereens using powerful dynamite, over several weeks, after several rounds of firing by anti-aircraft guns only managed to damage and not destroy these sturdy heritage artefacts.

All that we could reflect upon, in the mind’s eye was the spot with grand Buddha statues gilded with gold and decorated with “precious ornaments that dazzles the eyes with their brightness,” as one visitor had put it.

Journey to Bamiyan

Our journey to Bamiyan, in a Toyota HiAce, is a memorable one, as the vehicle has to go through large expanses which might once have been roads. When we set off from Kabul, and I naively asked Olivier Guillaume, councillor for cooperation at the French Embassy in Kabul, the distance to Bamiyan, he smiles and says: “In Afghanistan we never talk in terms of distance; but the number of hours.”

Given India’s popularity, it should promote movies with a strong gender theme, focusing on the education of girls and economic emancipation of women.

– An Iranian voluntary worker

Well, the 250km journey, given the state of the roads, took us a back-breaking 11 hours, nothing less. While we were nursing our backs, imagine the plight of our driver who had to negotiate tracts filled with boulders and potholes large enough to swallow his vehicle. Not to mention of running brooks on the road, formed by melting snow from the mountain tops.

But the relief came from the picturesque landscape, the small rivers that kept us company, at a level below, and the greenery of early spring, helped by an unusually good rainfall, which had brought cheer and hope of a good wheat crop.

But on the most inhospitable roads were located amazingly hospitable chaikhanas with friendly people and smiling children, offering us piping hot tea. Despite the status of the country, and their own poverty, there was no attempt whatsoever to fleece foreigners, including the very obvious westerners, the two Guillaumes!

As I look back upon my trip to Afghanistan, 16 years down the line, the dream is to return some day. The Covid pandemic has made travel that much more precious. And given the popularity of Bollywood then, I wonder who their popular icons are now. It was Shahrukh Khan and Madhuri Dixit then, along with Ajay Devgn, Aishwarya Rai and Preity Zinta. Music was back in Kabul after the Taliban’s ban on it was lifted, and you could hear Bollywood songs on Kabul’s streets. As also large posters of Bollywood stars!

But an Iranian woman, working for an NGO, had me thinking when she said: “I know India makes great films; but unfortunately, what we get in Afghanistan is the usual colourful song-and-dance romance stuff. But given the status of women here, and India’s popularity, your government should promote movies that have a strong gender theme, focus on the education of girls and the economic emancipation of women. The Afghan authorities certainly need inspiration from such movies!”

Pictures by Rasheeda Bhagat