Samantha Cristoforetti’s journey to space began during her childhood in a tiny village in the Italian Alps, her taste for adventure whetted by summers spent roaming the woods with cousins and winters skiing. But it was her voyages in books, read in secret under the covers at bedtime, that primed her imagination for her meteoric rise. “I doubt I’d be an astronaut today if I hadn’t climbed a ladder to the Moon many years ago, … if I hadn’t traveled all the way to China with Marco Polo or fought epic battles beside Sandokan” the pirate, she recalls in her 2018 book, Diary of an Apprentice Astronaut.

her fellow earthlings.

When she was 17 and a senior in high school, she travelled to St Paul, Minnesota, as an exchange student. “I was fascinated by space flight already. I was a big Star Trek fan,” she says. “All of that was centered in the United States.” One day, while eating out with her host mother, the two saw an advertisement for Space Camp in Huntsville, Alabama. Cristoforetti was all in. At Space Camp, she studied the space shuttle and simulated a 24-hour mission. “I got to go and play astronaut for the week,” she says. “It got me so much closer to the whole space thing.”

When she returned home, she went on a second journey, that of acquiring the skills she’d need to apply to become an astronaut, should that rare opportunity present itself. She studied engineering and became one of the first female fighter pilots in the Italian Air Force. “I wouldn’t say I was obsessed,” she says. “I always took pleasure in learning and doing what I was doing at that time. But I always kept the dream in mind.”

The European Space Agency had recruited astronaut candidates only twice before, most recently in the early 1990s, when Cristoforetti was a teenager. So when the agency announced it was accepting applications in 2008, she knew that was her once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Along with 8,412 other qualified applicants, she toiled through the astronaut recruitment process, which included aptitude tests, psychological evaluations, medical exams and interviews. She brushed up on her Russian language skills using a Harry Potter audio-book. (“I still have a small but enviable vocabulary of Russian magical terms,” she writes in her book.) Finally, she received the news she’d been waiting to hear — that she had fulfilled her childhood dream. “When you get that phone call that says you’ve been selected it’s like, Wow, what are the chances of this really happening?” she says.

In September 2009, she began training for missions to the International Space Station. For spacewalk training, she practised underwater to simulate weightlessness. She was fitted for both Russian and American spacesuits; the American gloves alone required 26 measurements. And she prepared for emergencies that she hoped would never happen — just little workplace mishaps like becoming untethered from the space station and floating away.

It was during one of these trainings that Bernd Böttiger, a member of the Rotary Club of Köln am Rhein, first met Cristoforetti. Böttiger, an internationally renowned specialist in emergency medicine, teaches astronauts resuscitation procedures in case of an emergency on the space station. “She impressed me as being extremely positive, extremely tough, extremely straightforward, extremely focused,” he says. “I can easily imagine how they found her among the thousands of applicants.”

In November 2014, after what may have felt like light years of training, Cristoforetti was ready to rocket to space.

Pusk,” comes the voice on the radio at the launchpad in Baikonur, Kazakhstan. Start. Fuel begins to flow into the combustion chambers of the Soyuz TMA-15M Russian spacecraft.

“Zazhiganiye.” Ignition.

“Poyekhali!” Let’s go! the crew’s commander, Anton Shkaplerov, shouts. Cristoforetti and crewmate Terry Virts join in his cry as they catapult into the air with a sudden jolt. It’s the same thing cosmonauts have been shouting since Yuri Gagarin, the first human in space, did so in April 1961.

Crews flying into space perform rituals that surpass even the long-standing Rotary traditions familiar to members. In the days leading up to liftoff, Cristoforetti details in her book, traditions include a screening of a Soviet-era film, a tree planting in Cosmonauts Alley, and a toast with fruit juice. Crew members sign their names on their hotel room doors, receive sprinkles of holy water from an Orthodox priest, and walk out to the bus that will take them to the launch site to the famous Russian rock song “Trava u Doma,” or “Grass by the Home”. And this will sound familiar to Rotary members: Once on board the space station, new astronauts may receive a pin, to mark their membership in an elite club.

As the seconds tick by on the Soyuz, Cristoforetti and her crewmates are pressed into their seats with increased force until, about nine minutes later, the engines cut off as they reach orbit. “In their thick gloves, my hands are dangling at about eye level, as if they weren’t attached to me,” she writes in her book of that moment. “In an immediate flip that flies in the face of millions of years of body memory, I have to make an effort to hold them against my body.”

They reach the space station in about six hours and, after a couple of hours of procedures, the hatch between the Soyuz spacecraft and the research station opens. With a gentle push from Shkaplerov, Cristoforetti squeezes through. It’s “like a second birth,” as she describes it, “one of those rare points of connection between past and future.” With that, she becomes the 216th person to live in the space station.

Since the first crew of one American and two Russians arrived in 2000, the International Space Station has been inhabited continuously by astronauts from 23 countries in something akin to a relay race, uninterrupted for 24 years. Cristoforetti has participated in two missions, her first from November 2014 to June 2015, at the time the longest ever for a woman in space at 200 days; the second from April to October 2022, which included a couple of weeks as space station commander, making her Europe’s first woman to hold the role.

Cristoforetti adjusted to all the space “firsts”: her first sleep (she opted not to tie herself to the wall with bungees and instead free floated in her phone booth-sized crew quarters); her first meal (scrambled eggs and oatmeal, which she set afloat so she could chomp it midair); her first trip to the bathroom (because of urine recycling, “yesterday’s coffee becomes tomorrow’s coffee,” she writes in her book). Then she got on with the business of being an astronaut.

Work hours run from about 7am to 7pm and start with a morning meeting. The station is first and foremost a scientific research vessel. During her missions, Cristoforetti has contributed to research on health topics such as the effect of noise on hearing, the maintenance of muscle tone and osteoporosis, as well as other areas of science like the physics of emulsions and the properties of metals.

Keeping the space station up and running falls to the astronauts, with duties like housekeeping (even in space, you need to vacuum), maintenance, and the loading and unloading of cargo vehicles. They’re also required to exercise 2.5 hours daily to prevent the loss of bone and muscle mass. Interspersed are meetings with their manager, flight controller, doctor or psychologist. When their work is done, they might call home or enjoy the view from the cupola, one of Cristoforetti’s favourite pastimes.

“Sometimes there are really busy weeks when you’re working all the time and jumping from one task to the next. You literally forget that you’re in space,” she says. “Floating is your normal way of locomotion. You kind of forget about what it feels like to sit or to walk.”

Still, she retained her sense of awe. On one of the final days of her first mission, she remembers spotting noctilucent clouds, a rare type of high-altitude cloud that thrills skywatchers with vivid blue wisps. “I’d been in space for over half a year, so you might think that you’re kind of jaded by then, but it was like, ‘Oh my gosh, here they are.’”

On her second mission, Cristoforetti participated in a seven-hour “extravehicular activity,” what the rest of us know as a spacewalk, the first by a European woman. She and a Russian crewmate deployed 10 nanosatellites as part of an experiment and did work on a robotic arm attached to the outside of the space station that assists astronauts with maintenance.

“It’s overwhelming to carry out — demanding psychologically and physically, especially if you’re a small female like me,” she explains. “It’s sheer concentration and willpower while you’re doing it, and then once you’re done, you can really let it sink in. It was such a feeling of accomplishment at having finally been able to do that. Just the experience of going out, it was amazing.”

In space, astronauts’ days are programmed by others; there’s no running to the grocery store or fighting traffic. Once they’re back on Earth, they experience something akin to reverse culture shock. And there’s that pesky thing called gravity. When Cristoforetti landed after her first trip, she details in her book, she borrowed a colleague’s phone to call her partner, Lionel Ferra, who also works for the European Space Agency. As she finished, she began to push the phone back toward her colleague as if it would float on its own. A classic astronaut mistake. She caught herself just in time.

Cristoforetti is an astronaut, engineer, fighter pilot — and a TikTok sensation. Her biography on the social media platform reads, “European Space Agency Astronaut boldly going where no Tiktoker has gone before.”

Her TikTok feed runs the gamut from science experiments to space life tidbits. Videos include how to use the space toilet, floating 101, and flying into the aurora borealis. In a clip about how to drink coffee in space, a foil pouch floats beside her as a graphic reading “coffee please” flashes on the screen and the song “Coffee Break” by Jonah Nilsson plays in the background. Incorporating a bit of science into the video, she demonstrates why a regular cup won’t work in microgravity and how her gravy-boat- looking mug uses capillary action to guide the liquid toward her mouth.

“I wanted to try something new and to make sure that we reached the young audience. Everybody was telling me they’re all on TikTok,” she says. “I was like, ‘It’s going to be a problem. I don’t even know how to dance. I’m not sure you can dance in space.’” But she gave it a shot and ended up having a lot of fun.

While the space station work was exacting, Cristoforetti found other ways to spice up life in orbit. Her first mission, the quintessential Italian teamed up with Lavazza to bring on board the first space espresso maker, dubbed the ISSpresso machine. She celebrated its arrival on a Dragon cargo spacecraft by changing into a uniform from Star Trek: Voyager. The espresso maker served double duty as a study in fluid mechanics. And as part of a UNICEF initiative, she sang the John Lennon classic “Imagine” from the space station cupola, one of many renditions by people all around the world that were included in a video released on New Year’s Eve 2014.

When she’s earthbound, Cristoforetti lives in Cologne with her partner and two children. Impressed with her character, Böttiger invited her to join the Köln am Rhein Rotary club between her first and second missions. “I thought it was a good place to bond with people who want to maybe live life with purpose,” she says. And who doesn’t want to dine with an astronaut? “It is really impressive to sit together with her at a table and eat and drink with her,” Böttiger says.

Beyond space, Cristoforetti’s work has taken her from the ocean floor (she lived 19 metres below the Earth’s surface for nine days as commander of NASA’s NEEMO 23 crew) to Norwegian fjords, where she participated in a field expedition studying lunar-like geology. It was practice for someday soon when astronauts will again explore the moon’s surface.

Having been everywhere from the ocean’s depths to outer space, where’s next for Cristoforetti? She ponders the question. “Will I ever go to New Zealand? I don’t know. It’s so far. It’s such an investment of time and effort. When I was on the space station, I flew over New Zealand every day. It was so easy, right?” she says. “I could just look out the window and, in a way, I was there.

“But at the same time, you’re kind of curious to see how it looks down there, so of course I’d love to go to Patagonia. I’d love to go to the mountains in Chile, all those places that become so familiar to you when you are in space. And yet, they are so far when you are on Earth.”

©Rotary

In some ways it’s just like any other Rotary meeting

Dozens of members of the Rotary Club of Köln am Rhein gather on a pleasant Monday evening at one of the famous Kranhaus office buildings, architectural gems shaped like upside down L’s over the Rhine River with the towers of Cologne Cathedral visible in the distance. The night’s speaker, an out-of-this-world member of the club, is scheduled to give the Rotarians a virtual tour of her workplace. The Wi-Fi connection on her end is finicky, and they wait eagerly.

At last, she appears, and that’s when this meeting takes a decidedly different turn. Because Samantha Cristoforetti, an astronaut aboard the International Space Station, is floating.

Cristoforetti is four months into her second stint on the space station, a research vessel about the size of a six-bedroom house that orbits the Earth every 90 minutes. Her hair set loose from the confines of gravity in a way that would make an ’80s metal rocker jealous, she takes questions and wows club members with the cosmic views. “Most of the time I try to take meetings from the cupola, because then you can show people the Earth from the windows,” she says in an interview with Rotary magazine.

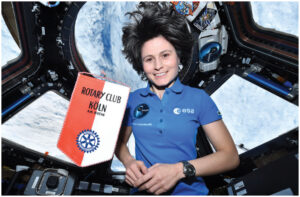

Astronauts’ personal items are rigorously monitored; they must meet a strict weight limit of only 3.3 pounds total. Among her select few items, Cristoforetti has included the red-and-white banner of the Köln am Rhein Rotary club. As the meeting closes, her fellow club members thank her with thunderous applause.

She rolls backward away from the camera, leaving the club banner on screen floating behind her