A progress report on polio eradication

We all know that Global Polio Eradication was championed by the Rotary International. Rotary therefore became a member of the quartet partnership of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative — World Health Organisation (WHO), Rotary, Unicef and US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) — a unique and unprecedented experience for Rotary.

Polio eradication, the largest and most ambitious global public health programme in history, is nearing completion: of the three types of natural (or wild) polio viruses, Type 2 was globally eradicated in 1999. Type 3 has not been seen anywhere since November 2012; probably that too has been eradicated but we must wait some more time to be sure. Type 1 continues to circulate in Pakistan and Afghanistan. India remains vulnerable to its import; to mitigate that risk we must sustain high population immunity. Hence Pulse Polio immunisation is continued in India even though we eliminated Type 1 way back in January 2011.

The second phase of polio eradication

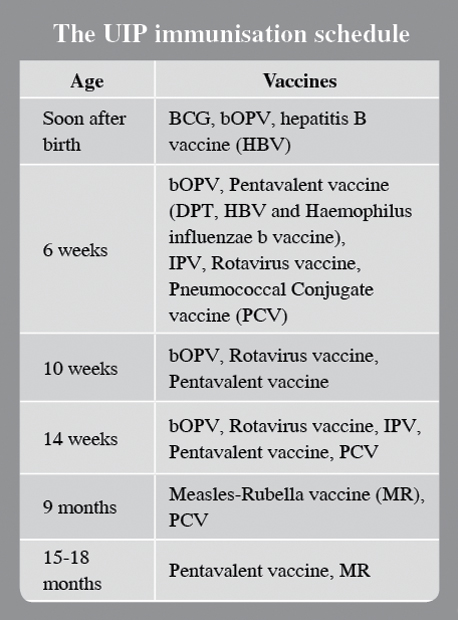

Also known as the ‘endgame’, the second phase is to withdraw the live vaccine viruses contained in the Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV), because they also can cause polio paralysis, though rarely. The risk-benefit ratio of OPV was highly favourable as long as wild viruses were causing polio in large numbers. Once wild viruses are eliminated, the risk is more than the benefit so we must withdraw OPV. Since wild Type 2 is certified eradicated, Type 2 vaccine virus was withdrawn in April 2016, in a dramatic move, globally and synchronously. Now we give only bivalent OPV (bOPV) containing Types 1 and 3 vaccine viruses. After wild Types 1 and 3 are eradicated globally, bOPV will also be withdrawn. When vaccine viruses are withdrawn, an immunity vacuum will be created — that is very risky and to provide insurance against any chance re-introduction of poliovirus, wild or vaccine, immunity cover must be created with the injectable Inactivated Polio Vaccine (IPV).

India has introduced IPV nationally; currently it is given as intradermal injections at 6 and 14 weeks of age, but this schedule may be modified.

Pulse Polio, a forerunner of PolioPlus

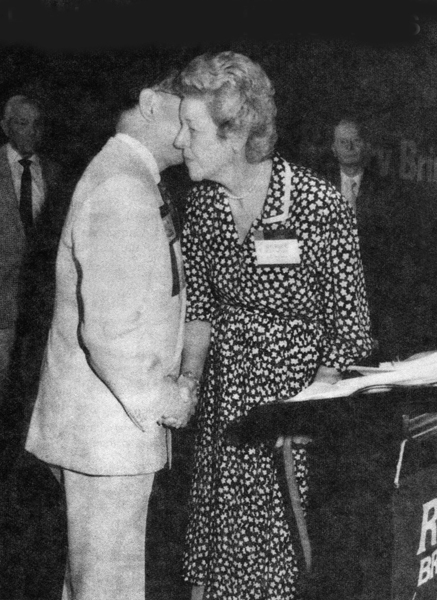

The term ‘pulse immunisation’ was coined in Vellore (Tamil Nadu) in the context of making the town polio-free during 1981–83 through a project of Rotary Club of Vellore and the Christian Medical College (CMC). Past RI President Clem Renouf visited Vellore in 1982 to watch Rotarian volunteers giving OPV to children during the Vellore pulse polio immunisation. Today ‘pulse polio’ is a well-known phrase.

But many of us don’t know what the ‘Plus’ is, in PolioPlus. The Plus indicates an addition to Polio immunisation. To understand it, let us go back in history and see how Rotary got involved in major health projects.

Traditionally service projects by Rotary were predominantly in the fields of education and economic and social development, including water supply and sanitation. Some local humanitarian projects included medical screening camps, eye-camps for cataract surgery, orthopaedic camps for corrective surgery of children with deformities due to polio etc. These were club or occasionally District-level projects, not global.

Health Hunger and Humanity (3H) Project

In 1978, Canadian Rotarians raised funds and applied for a Rotary Matching Grant for RC Madras for 78,000 doses of measles vaccine. That project was a game-changer. In 1978, the Indian Government had launched the Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI), designed by WHO. In India EPI vaccines included BCG, DPT and OPV, but not measles vaccine. Measles was a major problem in India — in rural communities about three per cent of children did not reach their fifth birthday on account of measles mortality. India urgently needed measles immunisation. However, there was widespread belief about ‘supernatural’ causation of measles and the worry was the possibility that rural folks might reject not only measles vaccine, but also all of EPI.

Grandmothers reminded us how the smallpox vaccine was welcomed by the people, in spite of popular belief about it being caused by Goddess Mariamman or Sitala Devi.

PRIP Clem Renouf told me that on the first day of The Rotary Foundation meeting in Singapore in 1978, the Canada-Madras measles vaccine project was turned down by the committee. That night Clem mentioned this to his wife saying he felt this wasn’t an important activity for Rotary to get involved with. She chided him and described how she had struggled with their children when they got measles. Measles is a terrible disease, and if some Rotarians want to protect children against it, TRF should encourage it, she insisted.

The next day the item was back on the agenda and passed. The project was called ‘the red measles project’ and it was later expanded under the 3H Programme to cover all of Tamil Nadu. The red measles vaccination campaigns in Tamil Nadu were a roaring success, conducted by Rotary with full participation of the government health department. Although measles vaccine was not licenced in the country, the then Chief Minister M G Ramachandran had obtained special permission for its use in Tamil Nadu.

In 1979, PRIP Renouf designed the 3H Programme. That enabled Canadian Rotarians to raise more funds under the 3H programme and increased measles vaccine doses to 3.7 million, as it was in great demand. Grandmothers reminded us of how the smallpox vaccine was welcomed by the people, in spite of popular belief about it being caused by Goddess Mariamman (in North India, Sitala Devi). The measles vaccination success in Tamil Nadu inspired the GoI to licence the vaccine and include it in EPI in a phased manner — from 1985 to 1990. With all WHO-recommended vaccines included, EPI was renamed as Universal Immunisation Programme, UIP.

The first 3H polio immunisation project was in the Philippines along with tetanus vaccination of pregnant women, and thus immunisation, especially of children, to prevent vaccine-preventable diseases — measles, polio and tetanus — became ipso facto a Rotary priority.

As feared in 1984, children protected from polio paralysis are still dying, though less frequently than earlier, of diphtheria, whooping cough, measles, and several other diseases that are eminently vaccine-preventable.

‘Polio 2005’ and ‘PolioPlus’ Committees

PRIP Renouf and other RI leaders wanted a mega project to celebrate the Rotary Centenary Year in 2005. He wanted a health related project and homed in to the idea of a ‘gift of a polio-free world’ to the children. His idea was accepted by the top leadership of Rotary and thus a “Polio 2005 Committee” was established in 1984.

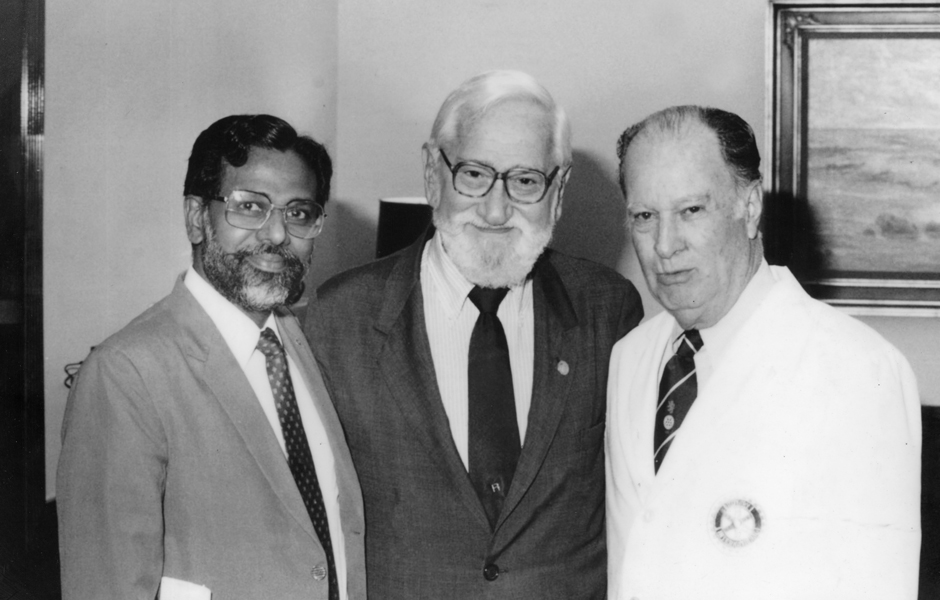

The “Polio 2005 Committee” was chaired by PDG Dr John Sever. RI President Dr Carlos Canseco was a member and Dr Albert Sabin, the creator of OPV, a special invitee. Thanks to PRIP Renouf, I was also included. Discussions focused on two items: Did Rotary want to go alone with providing OPV to all the children of low and middle income countries of the world, or did it want to join forces with WHO and Unicef and support global EPI? Dr Sabin strongly advocated that RI should go alone and conduct polio immunisation throughout the world. Two, how much funds should Rotary raise for immunising all the world’s under-five children with OPV for five years consecutively?

The final decision was that Rotary would spearhead polio immunisation for children globally, but do so with tacit support for EPI. We did not want children protected from polio paralysis dying of diphtheria, measles or whooping cough — all vaccine-preventable under EPI. In order to highlight this change in perspective, the committee was renamed “PolioPlus Committee” and the global Rotary Centenary Project was known as ‘PolioPlus’. The Plus indicated Rotary’s support for protecting children against all vaccine-preventable diseases.

The initial estimate for fund requirement was $120 million. For the first time in Rotary history, appeals for donations went to non-Rotarians and bilateral donor agencies. In 1985, donations surpassed $240 million — Rotary was now in the limelight for championing child health and survival in countries where under-five mortality was unacceptably high.

PolioPlus and global polio eradication

To be honest, PolioPlus Committee was not exactly thinking of ‘global polio eradication’ with the idea being born only in 1988. WHO has the world divided into six WHO regions — SE Asia, Western Pacific, Americas, African, European and Eastern Mediterranean. The Americas Region is administered by the Pan American Health Organisation, PAHO. No sooner than the PolioPlus Committee decided to give grants to countries proportional to the number of under-five children, PAHO made a decision, in 1985 itself, to eliminate polio in the Americas by 1990 and obtained a PolioPlus grant to kick start intensified polio immunisation for the polio elimination project.

Encouraged by the PAHO move and progress, WHO designed the concept of global polio eradication, and brought it to the World Health Assembly in 1988, where it was approved. The Assembly consists of Ministers of Health of all nations and a resolution passed in the Assembly is binding on all nations. WHO then received a grant from PolioPlus, to establish a unit in WHO headquarters to oversee the global polio eradication.

How satisfying is the popular sentiment — “No More Polio, Thank You, Rotary”. Today medical students are shown pictures of children with polio — real children getting infected by polio is a thing of the past.

The time for focusing on the Plus has arrived

As feared in 1984, children protected from polio paralysis are still dying, though less frequently than earlier, of diphtheria, whooping cough, measles, and several other diseases that are eminently vaccine-preventable. The UIP in India is fully funded and managed by the Central Government and implemented by the State Governments. But its success is patchy. The national average of the proportion of children “fully immunised” by age one has remained below 80 per cent for a number of years. The need is to achieve more than 95 per cent for all children, irrespective of circumstances, to share equally the benefits of immunisation — lives saved; health protected; scholastic attainment maximised; physical growth on par with richer countries — all these are benefits of full immunisation.

We sow much, but do not reap the full harvest. We invest adequately for preventing all vaccine-preventable diseases in all children, but the returns are not commensurate with investment in infrastructure, cold chain, staff and vaccines. Something is amiss — gaps in public understanding and acceptance of the benefits of immunisation. With PolioPlus experience, we Rotarians are experts in public education and ‘social mobilisation’ to make UIP a complete success.

An opportunity and a responsibility for Rotary India

As seen above, India has an ambitious programme to protect children from a number of vaccine-preventable diseases. We Rotarians in India have a great opportunity to work with the Government in promoting immunisation so we can prevent diseases in our children and protect their health.

Disease prevention allows better school attendance and scholastic performance. That will later on lead to better employability and higher incomes. Families will save from unnecessary healthcare costs of sick children with vaccine-preventable diseases. We know how to work in communities; we know public health education and social mobilisation.

The Plus in PolioPlus is thus a broad agenda. Through immunisation, we will be able to serve the causes of education and social development. Thanks to the visionary leadership of great Rotarians, like Clem Renouf and Carlos Canseco.

The author, a past president of RC Vellore, is a virologist, and Founder-member, PolioPlus Committee of Rotary International.