Haq achchha. Par uske liye koi aur marey toh aur achchha. The packed hall burst into laughter when chief guest Arun Shourie recited these lines by Pakistani poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz which declare that it’s good to have rights but if someone else dies upholding them, it’s even better! This was at the inauguration of the just- concluded Lit For Life in Chennai, promoted as the sharpest literary festival in the country, and Shourie was making an impassioned plea for the freedom of speech and creative expression, urging that we stand together and speak up when fundamental rights are threatened or violated. Faiz’s lines instantly resonated, proving yet again that there’s nothing like poetry to reach directly to the heart.

The discovery of a collection of Subramania Bharati’s poems simultaneously published in Tamil and English goaded me to climb a short ladder at home to reach up to two shelves of poetry coated with the dust of years. Sneezing and snorting I brought the books down and embarked on a nostalgic trip. Swirling around in my head were lines from Bharati. In one he thunders Acchamillai, acchamillai, acchamenbadillaiyey / ucchimeethu vaanidinthu vizhuginra bothinum / acchamillai, acchamillai, acchamenbadillaiyey (We have no fear, no fear at all, even if the skies break and fall on our heads, we have no fear). In another he tells children to run about and play together: Odi vilaiyaadu paappa… koodi vilaiyaadu paappa. He burned with the desire for freedom and the emancipation of women, even as he sang about wiping out discrimination of every kind, stomping up and down streets, reciting his poems in an impassioned frenzy — all this by the time he was 39, when he died (in 1921) following complications after having been trampled upon by a temple elephant.

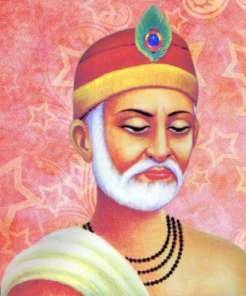

Bharati naturally leads to Kabir. Anybody who has studied Hindi in school will know the doha (couplet): Kasturi kundali basey, mrig dhoondai ban mahi /Aise ghat ghat Ram hai, duniya dekhe nahi (the deer roams the forest following the scent of musk which actually lies within itself, even as we seek god outside ourselves). Or this one: Bura jo dekhan main chala, bura na miliya koy / Jo dil khoja aapana, mujhsey bura na koy (I sought the bad in others but discovered, when I looked within, that there was no one as bad as myself).

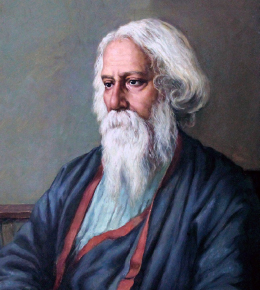

The search naturally led to the master who wove pure magic with his words: Rabindranath Tagore who turned down a knighthood from the British in protest against the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, saying the bejeweled necklace did not become him, it hurt him to wear it (Ei monihaar aamaay naahi shaajay / Erey porthey geley laagey, erey chheenthey geley baajey).

This brought back memories of a late evening in Ooty (now Udagamandalam), sitting on a low wall by a sloping road just outside the home of a dear friend’s aunt, singing Rabindra Sangeet to our heart’s content. One of the poems her uncle recited that evening was about a dusky beauty called Krishnakali whom the whole village calls ‘dark’, in which every stanza ends with the line: Kaalo? Taa shey jotoee kaalo hok, dekhechhi taar kaalo horin chokh (Dark? No matter how dark she may be, I have seen her black gazelle eyes). This line sends a shiver of delight up my spine each time I recall it.

Ho Chi Minh, the venerable Vietnamese leader, former prime minister and president, who led the independence movement of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and who worked towards the unification of North and South Vietnam, wrote a series of poems when he was a prisoner of the Chinese in 1942–43. He was smart enough to write in Chinese so that his captors could read what he was writing and thus would not be suspicious, as we often are even when we hear people speak in a language we do not understand. The edition of Prison Diary on my bookshelf has the poems in Chinese, Vietnamese and English! Here’s one small sample from Uncle Ho:

Neither high up nor far away/On neither emperor’s nor king’s throne/You’re only a little slab of stone/Standing on the edge of the highway.

People ask you for guidance/You stop them from going astray/And tell them the distance/O’er which they must journey.

The service you render is no small one/People will remember what you’ve done.

Some of you may remember reading in the papers in 2002 about a young man unfurling the Tibetan national flag and a banner screaming ‘FREE TIBET’ from the 14th floor of Mumbai’s Oberoi Towers when the Chinese Prime Minister Zhu Rongji was addressing business people inside the building. In 2005, you may have read about this young man protesting similarly when the then Prime Minister, Wen Jiabao, was in Bengaluru. The young man was Tenzin Tsundue, born in a refugee camp in India, and yearning for his homeland. I happened to meet him some years ago in Rajkot where he presented me with a slim collection of his writings, titled Kora. The first entry in that book is a poem that brings a lump to the throat every time. Here it is, ‘Horizon’:

From home you have reached/the horizon here.

From here to another/Here you go.

From there to the next/next to the next/horizon to horizon/every step is a horizon.

Count the steps/and keep the number.

Pick the white pebbles/and the funny strange leaves.

Mark the curves/and cliffs around/for you may need/to come home again.

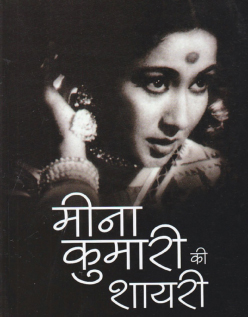

The need to find your home and the unstoppable passage of time are only two of the myriad themes that run through poems. The best remain impressed upon your heart forever. Actor Meena Kumari’s inner life and churning permeate every poem in the collection, Meena Kumari Ki Shayari, introduced and collated by lyricist Gulzar to whom she willed her entire body of writing upon her passing. This poem is called Lamhe (Moments):

Kayi lamhe /Barsaat ki boondein hain/Naakaabiley-giraft/Seeney par aakar lagtey hain/Aur haath baddhaa/Ki issey pehley/Phisal kar toot jaatey hain (Moments are like raindrops, they cannot be held. They fall upon you and before you can catch them, they slip away and break).

In One Hundred More Poems From the Japanese by Kenneth Rexroth (translation, obviously), there is this gem by Saigyo, which seems somehow connected to Meena Kumari:

Why should I be bitter/About someone who was/A complete stranger/Until a certain moment/In a day that has passed.

Wow! In Japanese, just for the sound of it and of course for those who know the language, it goes (transliterated in the Roman script): Utoku naru/Hito wo nanitote/Uramuramu/Shirarezu shiranu/Ori mo arishini

As the 17th–18th century Sufi poet Bulleshah, writing in Punjabi, says: Sab ikko rang kapayee da / Ik aapey roop vataayee da (Cotton is always white, and cloth of different colours is made from this cotton). So simple, so true, completely unforgettable. They say truth is beauty, beauty truth. This is the beauty of poetry, this is the truth of poetry. A brilliant collection of “remembered verses from pre-modern South India” called Poem at the Right Moment reminds us of this sentiment in a short Sanskrit poem:

Samsaara-visha-vrikshya dvey phaley amrutopamey/Kaavyaamruta-rasasvaada sangatthi saj-janaih saha

In other words: The Tree of Life is bitter/but it has two sweet fruits:/good poetry/and a good friend.

Indeed. Good poetry and a good friend. What more could we want?

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist.