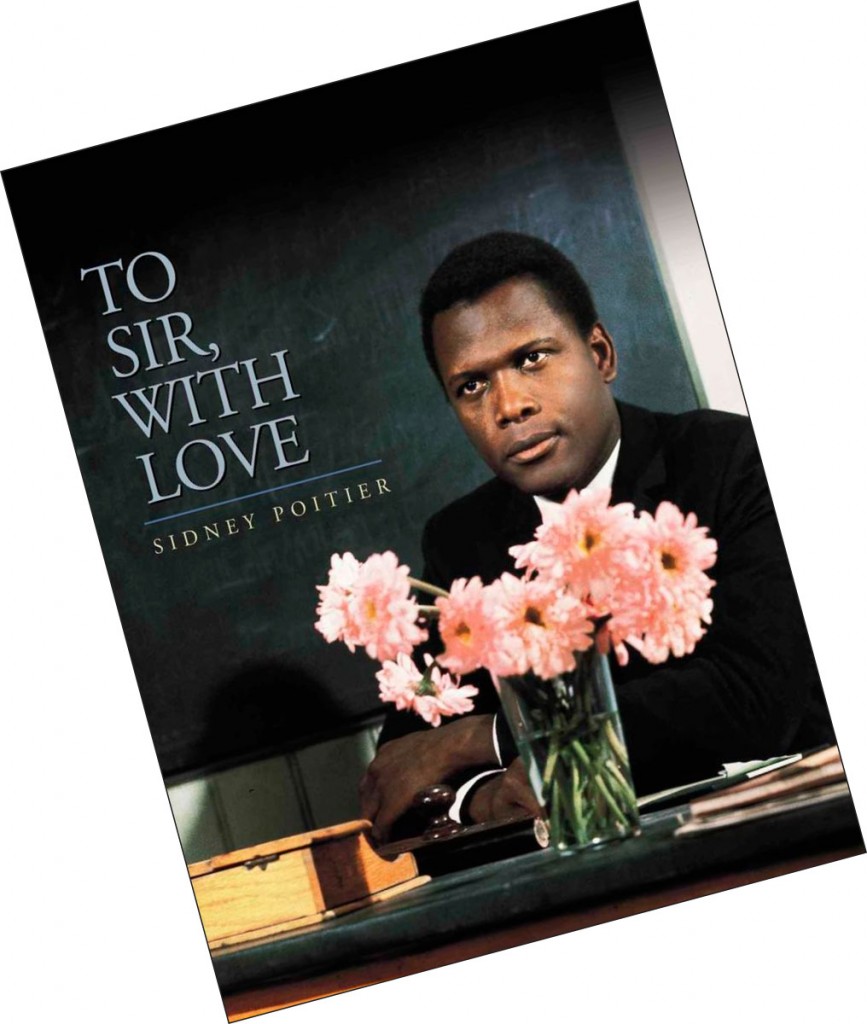

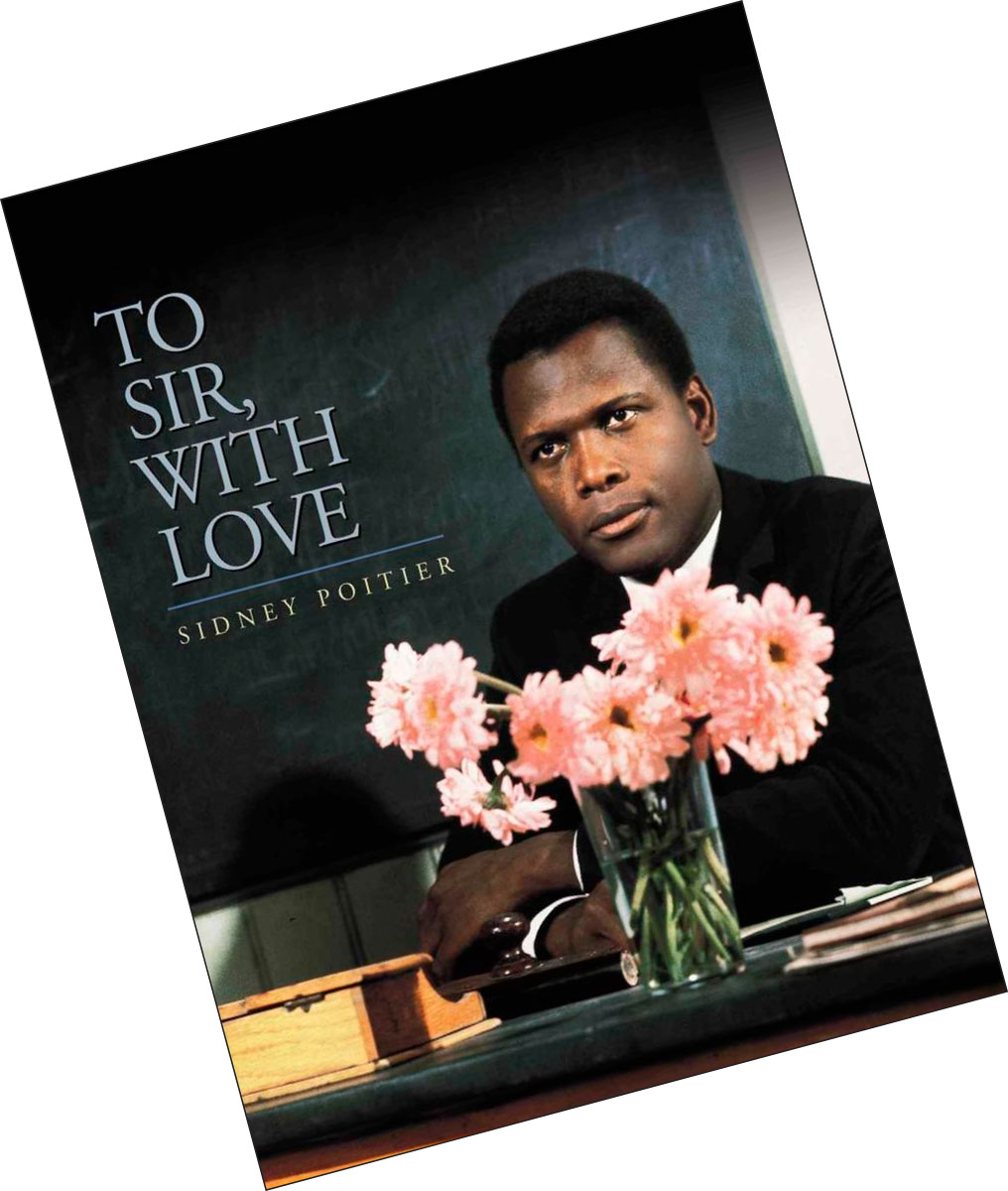

Sidney Poitier famously starred in a 1967 film called To Sir With Love in which he plays a teacher dealing with rowdy students in an East End of London school. It was based on an autobiographical novel of the same name by E R Braithwaite published in 1959. That teacher was something of an ideal and rising to the challenge. An ideal teacher is a window to the world no matter who the students, at any time, at any age. People usually remember teachers with nostalgia, although many may not have such pleasant memories. Still, September 5 is routinely celebrated as Teacher’s Day in India after the birthday of former President and eminent scholar, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan.

Barely ten days before Teacher’s Day, a seven-year-old Muslim boy in a school in Muzaffarnagar, UP, who apparently had not learnt his multiplication tables, was given a bizarre punishment by his teacher, Tripta Tyagi. She got all the children in his class — 6–8 year-olds — to line up and slap him hard, one by one. This is not the first nor last instance of teacher misdemeanour, it’s just that few such incidents are reported in the media. We know that corporal punishment is illegal. We know that discrimination is unacceptable. Still, these things happen, to our shame. More shameful is this teacher’s behaviour. Ordering her little wards to engage in violence against a class fellow? Teachers lead by example. This teacher only feels and teaches hatred. I guess she’s not much of a reader. Education is in large part about books and reading, just what Wordsworld tries to bring to his readers. Further, this would be of interest to Rotarians given their commitment to making education available to the less privileged.

What has this to do with books? A lot. Reading about different people can go a long way in giving us truer understanding of the world and its inhabitants. One such book is Baluta, written originally in Marathi by Daya Pawar. Translated into English by Jerry Pinto, it caused a sensation when first published in 1978 ‘not just with its unvarnished depiction of the pervasive cruelty of the caste system, but also the extraordinary candour with which Daya Pawar wrote about himself and his family, his community, and Dalit politics of his time,’ to quote from the back cover of the book.

Writer Shanta Gokhale writes in the preface to the book, that as ‘liberal Brahmins,’ she was brought up to deny caste. Daya Pawar was a Mahar. She says: ‘I was ignorant of all the humiliating specificities of what being a Mahar meant. I didn’t know that Mahars skinned dead cattle and ate their flesh. I didn’t know that Mahar children were made to sit apart from the upper classes in village schools. I didn’t know that their touch was supposed to pollute water, rendering it undrinkable for the upper castes. Baluta opened this other world to me without mincing words, in direct, simple language, making escape impossible. I had to look at Daya Pawar’s world as part of the reality of being Indian. It filled me with shame.’

‘The reality of being Indian…’ is the phrase that must awaken our conscience and consciousness. In all the narratives of India-that-is-Bharat rising and shining, and the spring-cleaning of the capital city during the G20 meet, we need to remember the ‘reality of being Indian’. The word, baluta, derives from a practice that kept the Mahars bonded in the village. They got a share of the produce in return for services to the village at all times, such as making funeral announcements in villages, dragging away the carcasses of animals, tending to animals, playing music day and night at festivals and weddings, and so on.

Here’s a short excerpt from Baluta, pertaining to school: ‘We were not allowed to sit with the Maratha children from the village. They faced the teacher and we sat at right angles to them, facing in a different direction. If we were thirsty, there was no water for us at school; we had to go back to the Maharwada to drink.’ And something about the teacher: ‘When he was in school, we did not get the feeling that he discriminated on the basis of caste. But when we went to his house, he underwent a radical transformation. He became “pure”, in the ritual sense of the word. … we could not cross the threshold; we had to stand on the steps. The goods would be given in such a way that not even a finger touched us. The master we knew at school did not resemble the master in his lair. It was as if he had his caste consciousness hanging on a peg near the door and he could slip into or out of it, at will.’ The writing is lucid and eminently accessible, even amusingly ironic at times. Yet, as you read, you see how so much has remain unchanged, despite the passage of time.

As happens occasionally, more books came my way, one by chance and the other, the choice of my book club read for the month. The first is a light, engaging detective novel set in Bengaluru by Harini Nagendra, called The Bangalore Detective Club. Set in pre-Independence times and featuring a traditional young woman with out-of-the-box ideas, it’s a breezy read, good to take along on a trip or to get a break from meetings. An added attraction is the way chapters have been titled: Swimming in a Sari, Men Can Make Coffee, Disappearing Lathis, Conversations Around the Pool!

The other evokes Frenchified Pondicherry. Called The Thinnai and written by Ari Gautier, it’s been Englished by Blake Smith. The Thinnai, or veranda in Tamil, is where, typically, residents would sit in their free time and watch the world go by, chat with friends and family. In the novel, an old Frenchman comes to the thinnai of the narrator of the novel and shares a story that covers a host of curious characters and the history of France’s colonial connections with India. The nicknames given to various characters — Joseph One-and-a-Half-Eyes, Emile Kozhukattai-Head, Jean-Claude Cow Shit — remind you of Raja Rao’s seminal work, Kanthapura, published in 1938 — Pockmarked Siddamma, Post-office-house Suryanarayana, Four-beamed-house Chandrashekarayya. Kanthapura looks at the impact of Gandhiji on a small south Indian village, with a focus on the prevailing caste system.

A short excerpt in the narrator’s voice should provide a feel of The Thinnai, a slim novel: ‘Life in Kurusukuppam condensed around our house. Pattakka had her idli stand across the way, the fountain was just a few metres away and the only shop in the neighbourhood was on the main street by the playground. Karika Bhai, who ran the shop, was the only foreigner in the neighbourhood. His real name was Amanullah, and he was a Malaysian-Indian. But he couldn’t avoid getting a nickname anymore than anyone else in the neighbourhood could.’

I cannot help but think that it’s no coincidence that the Muzaffarnagar incident and these random titles all tie in one way or the other with issues of social status, caste, the past, the present and our place in history. Even The Bangalore Detective Club, you will discover.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist