For a long time, when I pushed open the curtains in the morning, I saw a small white cat sitting curled up beneath the coconut tree, staring intently at me, almost as though we had an ‘otherly’ connection. Or is it earthly? My son’s friend, for instance, is married into a conservative family, but they adore dogs. They have two or three pet canines, and the arrival of each, as a puppy, is greeted with a visit to the temple and special pujas performed in their names. The pets participate in every function in the family, be it social, celebratory or religious, and when they fall sick, it’s not only vets that attend on them, but potions and prayers to ward off the evil eye.

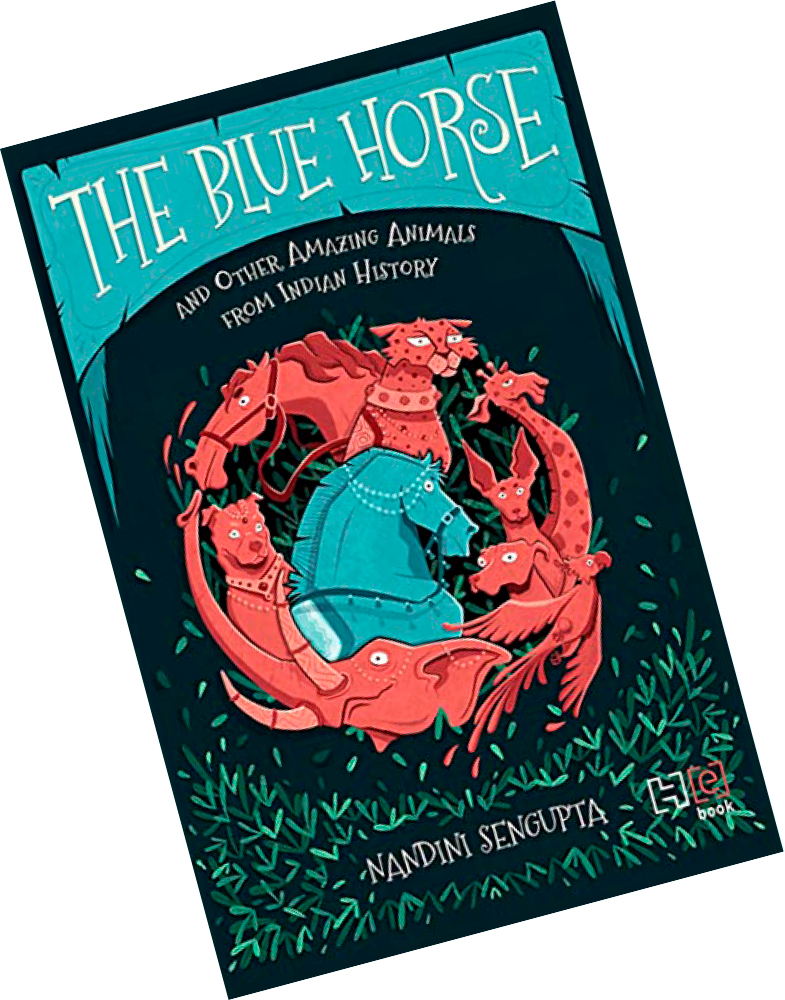

The bond between humans and animals is as old as they have been around. All animal-lovers have stories to share — stories that make you laugh, move you to tears or amaze you. Nandini Sengupta has written just such a book: The Blue Horse, and other amazing animals from Indian History. As the top line on the back cover says: ‘It’s not just humans who make history, you know.’ Although the publisher has categorised it as a children’s book, this beautifully written and engaging paperback is most definitely for all ages, it’s one for the family from the littlest one up. If you love animals and history, then this one’s especially for you!

We’ve all heard or read stories about the valour of animals. Many schoolchildren can recite Shyam Narayan Pandey’s poem ‘Chetak ki Veerta’ about Maharana Pratap’s horse. It’s possibly one of the most well-known animals in India, and that’s probably why the book is called, after Chetak, The Blue Horse. The blue horse? ‘I am a Kathiawari horse,’ says Chetak. Incidentally, the stories are all told in first person. ‘Not as big and imposing as an Arab stallion, but sturdier and just as fast. And then there’s my dappled grey coat, which earned me the sobriquet of the ‘Blue Horse’.’

The Nawab of Junagadh held a lavish, three-day celebration for the marriage of his favourite pet dog, Roshanara, with Bobby, a pet belonging to the Nawab of Mangrol. Both dogs were heavily bejewelled and taken in a procession.

Chetak goes on to say: ‘Maharana Pratap was an exceptionally tall man. And strong as an ox to boot. Bard songs say he weighed nearly 200kg in his full chain mail and armour, fitted with all his weapons! I am not sure about the numbers — I am a horse, not a maths teacher! — but it was a heavy burden I carried on my back. Remember, I also wore armour — my Pakhar saddlery, my Jhool mail and caparison clothes, all of which weighed a lot too. But weight or no, I had to be quick, or Hukum and I would both be dead.’

The descriptions in the book are detailed and engaging; they are based on historical facts, unearthed after painstaking research and cross-checking by the author. Yes, the Nawab of Junagadh did in fact hold a lavish, three-day celebration for the marriage of his favourite pet dog, Roshanara, with Bobby, a pet belonging to the Nawab of Mangrol. Both dogs were heavily bejewelled and taken in a procession. The author provides the sources for the details at the end of each story. The info-box at the end of ‘The Wedding Belle’ mentions the source of the information as The Dog Book: Dogs of Historical Distinction by Kathleen Walter-Meikle. The info box at the end of Chetak’s story, for instance, can clarify — for those who wish to know — the historical position on the Battle of Haldighati which, in recent times, was embroiled in controversy following the rewriting of some portions of it in school textbooks. As Nandini points out, this event is well-documented by Mughal chroniclers as well as Rajput bards; she draws attention to the view of contemporary historians that there was no clear winner: Maharana Pratap lost many soldiers and had to leave the battlefield while the Mughals could neither kill him nor end the Rajput resistance.

Jayakesi had promised to protect his parrot from the wiles of the cat and if he did not do this successfully, he had promised that he ‘would follow him to the next world’. So, when the cat finally got the parrot, he honoured his promise.

It’s not surprising that many of the stories are about dogs, but there are cheetahs and elephants too. And an extraordinarily beloved parrot that belonged to a scion of the Kadamba dynasty in what we now know as Goa. The author says she first came across this story in ‘a passing reference by historian Upinder Singh in her seminal book A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India’ in which she ‘referred to a 12th-century inscription at Tambur that talks of the king who killed himself for his parrot’. Further research revealed more details. As the parrot says, ‘It isn’t every day that a human, much less a king, gives up his life for the sake of his pet parrot. But then again, I was no ordinary bird. I was a talking parrot who had been trained to recite the Vedas and discuss Chanakya Niti. And my loyal human was a king called Jayakesi.’ Now, in that palace prowled a cat intent on making a meal of the parrot. Jayakesi had promised to protect his parrot from the wiles of the cat and if he did not do this successfully, he had promised that he ‘would follow him to the next world’. So, when the cat finally got the parrot, Jayakesi honoured his promise.

‘To be honest,’ the author has the parrot say, ‘I didn’t expect Jayakesi to stick to his promise. There was no one in the room when he made the vow. And humans don’t value their friendship with animals the way animals do with humans. To them, it’s just a few moments of amusement. To us, it is our whole life. But Jayakesi was different. It didn’t matter to him that his promise was made to a bird. And that the bird was now dead and could not speak for itself. He ordered a funeral pyre piled high with sweet-smelling sandalwood and climbed inside, holding me in the palm of his hands.’

My son’s friend has two or three pet canines, and the arrival of each, as a puppy, is greeted with a visit to the temple and special pujas performed in their names.

I was so enthralled and enchanted by this book that I wanted to chat with the author about it. After all, she was practically my neighbour, in Pondicherry, barely 170km away from Chennai! Nandini was more than generous and answered all my questions passionately. She had been researching the Akbarnama — the official chronicle of Akbar’s reign written by Abu’l-Fazl ibn Mubarak — for a book she was working on, when she came upon a reference to the cheetahs. One thing led to another and the idea for this book was born. ‘I am a history evangelist, and an animal evangelist,’ she says. The cheetahs open this collection, and the names they are called by in the story — Samand Manik, Madan Kali, Chitranjan — are the actual names of Akbar’s cheetahs. Nandini says the book is only 15 per cent embellishment, the rest is historical facts.

The world knows of many animals that have made a mark on history, and some of them find mention at the end of the book, such as Caligula’s horse Incitatus, King Dutugamunu’s war elephant, Queen Isiemkheb’s pet gazelle, Genghis Khan’s falcon, Emperor Yongle’s giraffe and so on. But Nandini consciously chose to focus on Indian animals. ‘They are known so little,’ she says, and she would like them to be known. For about two years, she researched, located authentic sources, and wrote their stories. She located many animals that had played a significant role in Indian history, but the book tells the stories only of those that could be clearly attributed to authentic sources. That’s why it’s a slim book, but who knows, perhaps the next edition will be thicker because the research continues. Meanwhile, The Blue Horse is a beautiful way to experience adventure and get a taste of the past, source and all.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist.