My maternal grandfather was a doctor and after he retired from government service, he volunteered at the clinic run by the Ramakrishna Mission on Royapettah High Road in Chennai. I was in a boarding school in Chennai, and every time I visited my grandparents, either over a weekend or during the Christmas holidays, I would tag along with him to the clinic. While thatha headed straight down the corridor where queues of patients anxiously awaited his arrival, I made for the library situated further inside the campus.

To my child’s eye, it appeared as though the campus were huge and the library cavernous. On my first day there, thatha accompanied me and left me in the charge of a saffron-clad monk who was probably the librarian. But from the next visit onward, I was on my own and soon I felt I owned the place: the shelves, the books, the library itself. There were no other children around, only monks and lay adults gliding silently between the shelves. But nobody took any notice of the child picking up books at random, sometimes smelling the pages and sometimes flopped on the floor, reading.

You can guess what kind of books adorned those shelves: mostly philosophical, a lot to do with Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, Sharada Devi, Swami Vivekananda and other venerated individuals, tomes of serious texts in a splattering of languages, some recognisable, some to be wondered at. Not exactly the kind of reading list that would appeal to an 11 or 12-year-old! But I didn’t care. They were books and I was a bookworm and in my world, the twain always met! Even so, I used to get a special thrill every time I chanced upon stories that I could comprehend. And so I read about Ramakrishna, Vivekananda and other enlightened souls, stories that I have now forgotten — but not the library that housed them.

When we were kids growing up in a small town in West Bengal, my friends and I pooled our literary and financial (meagre at best) resources and ‘built’ up our own private library. We knew nothing about either the Dewey system or colon classification but we had our own way of keeping track of the books and charged anything between 10 paise and 25 paise as borrowing fee. Borrowing books from our library soon acquired some kind of cult status and we vied with each other to see who had read the most number of Famous Fives or Biggles or whatever else was on offer. Our small collections went into ‘stocking up’ the library which was housed in a room donated to us by a bachelor ‘uncle’ in the neighbourhood. Incidentally, he also prepared a badminton court for us in his backyard. After that, he discreetly retreated to the shadows.

Now, thanks to information being freely available, we know that the Dewey Decimal Classification used in libraries in many parts of the world makes it possible to find any book on the shelves and, in reverse, to return it to its exact place. This may not seem like anything special because we take the system for granted now. But when you realise that before this system was put in place the practice was to organise books in libraries according to the order in which they were acquired rather than by subject and all that ended up doing was get the library disorganised, you understand what a radical invention that was from Melvil Dewey, as far back as 1876.

However, Dewey is not the only purveyor of library science; there is also S R Ranganathan who introduced the colon classification system. This mathematician, university librarian and professor of library science was appointed by the University of Madras in 1923 to make sense of its messy collection of books and journals. Initially, he was bored stiff with the job; he longed to get back to teaching. So the university offered him a carrot: go study contemporary western library practices in University College London and if you’re still not motivated, return to teaching.

Ranganathan took the bait and once he started applying his mathematical brain to the research, he was hooked. He began to see the ambiguities in the Dewey system (among other things) and, to cut a long and fascinating story short, he revised the system and devised a clearer way of classifying books so that identifying and retrieving books and information became simpler. He returned to India in a much happier frame of mind, even going so far as to put the ship’s library in shape on the long voyage home! He remained with the University of Madras for 20 years and worked tirelessly for the setting up of free public libraries in India. Given Indians’ penchant for connecting relationship dots, S R Ranganathan is often referred to as the ‘father’ of library science in India.

Still, there are very many schools in India that do not have libraries. There are libraries that blanket-bind the books a dark blue or green or black so that the user has no idea what the book cover looks like, nor can read what’s on the back cover. I remember the iconic Connemara Public Library in Chennai used to have shelves and shelves of seemingly forbidding materials that you would not ever be tempted to look at. Yet it’s a treasure house, as many bookworms have discovered. There’s nothing you cannot find there; you only require patience. Established in 1896, it receives a copy of all books, newspapers and journals published in India.

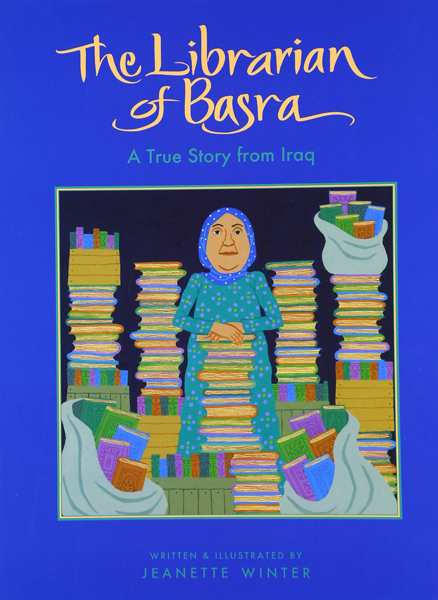

The seminal value of libraries is brilliantly illustrated by an iconic picture book by Jeanette Winter called The Librarian of Basra. Based on a true story, it tells of Alia Muhammad Baker, a librarian in Basra, Iraq, who with help from the local community, saved the books in her library from being destroyed during the war by secreting them out of the building before the marauders arrive. The Jaffna Public Library in Sri Lanka, one of the biggest libraries in Asia with over 97,000 books and manuscripts, was not so fortunate. In what must surely be the most violent example of the war against knowledge, it was burnt down by a rampaging mob on June 1, 1981. It has since been reconstructed, but those old books and papers are lost forever.

Libraries are spaces of the free mind, they are spaces that free the mind. Libraries are home to ideas across centuries and peoples. Their energy derives from the multilayered experience of reading. That’s why dictators, invaders, the power-crazed are afraid of books and libraries. And that’s exactly why we need books and libraries, we must protect them, nurture them and ensure their growth and existence. The best way to do that is to use them and encourage others to do so as well.

Yet, I have been at a discussion in the course of which one teacher, the vice-principal of a school no less, said children shouldn’t be given books because they mishandle them. Luckily another individual responded by saying libraries should be judged by the number of mishandled books they carry. The more soiled books the better the library. It is proof that children are reading!

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist.