In my journey through textiles, I have been fascinated by ikkat, a jagged melding of colours as warp marries weft in patterned symmetry, creating poetry on fabric. Ikkats are woven only in Japan, Indonesia and India.

I hit the ikkat trail, and was richly rewarded by discoveries in Odisha, Gujarat and Andhra, where it is prominently produced.

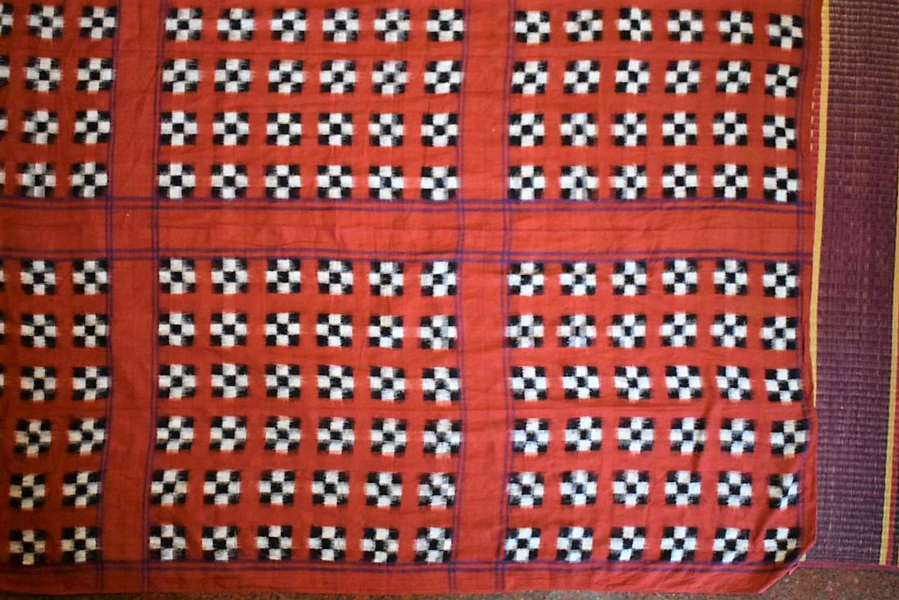

When my husband and I travelled to Hyderabad in the 1980s, where I showed my collection of woven and hand-printed saris from Madras, a visit to Puttapakka paid rich dividends. In a modest little home, one weaver told us stories, of how his ancestors originally migrated from Saurashtra and settled in Chirala in Andhra Pradesh, which formerly produced the finest weft ikkat in the form of rumaals used by rich Muslims. I gasped when I picked up a soft mull cloth in blazing natural dyes of black and red, just 55 or 75 sq cm, in bold geometric patterns with wide bands of plain red as border. I was told that up to the beginning of the 20th century, these were specially woven for lungis, shoulder cloth and turban cloth, popular import items in many Islamic countries.

The weaver explained that the yarn is soaked in oil before weaving, hence the acquired name telia rumaal. The oil softened the yarn, making the finished textile as soft as a cloud. I thought aloud. Why not extend this technique to brilliantly designed sarees? I could help, and we could reproduce ancient telia designs.

“Amma, just very recently, this has been done by Madam Pupul Jayakar, and Martand Singh for the Festival of India,” he said. It excited me to think that a whole less travelled route was opening up and we would see a plethora of exquisite sarees in the market.

Originally, it was the cotton telia rumaals which were made in Chirala. The finer of the designs were taken by princesses to wear as veils with a little surface ornamentation, such as tinsel embroidery. Sold as handkerchiefs, these exquisite weaves incorporated contemporary motifs like aeroplanes and clocks, and the colours were usually black, red, dark brown, white and pink.

Puttapaka specialises in weaving the double ikkat and imitating the traditional patola designs. Today the area has a captive market with exquisite saris in mercerised cotton and silk, and designer dupattas, flowing out of the looms in astounding design innovations. The weavers belong to the Padmasali community, and have proved most ingenious in inventing new designs, their versatility paying rich dividends.

We travelled to Pochampalli in Nalgonda district, a village abounding in ikkat weaving. As you walk into the village, your senses are assaulted by a mind-boggling array of ikkat fabrics and saris stacked everywhere. Ikkats are woven in Jalna and Golconda apart from Chirala. Ikkat weaving here, unlike Odisha, seems to be a recent development, probably the late 19th century, when most of ikkat weaving was restricted to scarves meant primarily for export to Arab countries. It was around the 1950s that ikkat weaving flourished in Pochampalli, where the ikkat is without the extra weft threads and is simpler in form than its Odisha counterpart. The designs are bold and in vibrant colours, often geometric and abstract in design. Usually a grid-like design is woven, though geometric birds or animal figures are intricately executed.

The finer cotton telia rumaals were worn by princesses as veils with a little surface ornamentation.

Andhra is the largest exporter of ikkats compared to the other States. With proper nurturing, some of the master weavers here have reached heights of excellence and made a name for themselves, their business growing manifold. It is this status that we wish for all the weavers in the country.

Patan Patolas Gujarat

Attend any Gujarati wedding and you are bound to find numerous women wearing gorgeous patan patolas in multi-coloured hues, the colours spliced together in an unerring symmetry, the saris as beautiful as the plumes of the bird of paradise!

The origin of patola is clouded in conjecture, but ancient historical evidence lies in the Ajanta frescoes going back to the 6th and 7th centuries, depicting monks and women wearing robes made of ikkat-like fabrics. That the double ikkat existed in the 17th and 18th centuries is very likely, judging from the wall paintings of the Mattancheri and Padmanabhapuram Palaces in Kerala.

Patola originating in Gujarat uses a double ikkat technique and is an extremely complicated process. In patola, the warp and the weft are separately tie-dyed in accordance with the required patterns, and this complicated process reflects the acme of weaving skill. Kumarpal, son of a Jain king, brought in 700 Salvi families to settle in Patan to weave patolas exclusively for him, and it is believed that they have lived there ever since.

Owing to the complexity of the weaves the patola is expensive, with a saree costing about Rs 1 lakh or more.

The patolas are essentially used for ceremonial garments. In Gujarat they are traditionally worn by Hindus, Jains and Vohra Muslims, but they were also used on special occasions in Maharashtra and South India. Owing to the complexity of the weaves the patola is expensive and not affordable by all, with a saree costing about Rs 1 lakh or more. Till today, it is considered an auspicious fabric for the bride.

The Burmese word for the fabric was gausing — that which chases away disease. It was probably this that caused pregnant women of the Vohra community to use patola during certain stages of their pregnancy. In South India, it was once used as textile hangings, or covering for temple elephants. In Kerala, the patola was used to wrap and decorate the idol, and for tantric rites. It was supposed to have medicinal value, particularly for treatment of burns.

The most popular and traditional design of patan patolas is the poppat kunjar design, which is considered auspicious and where the motifs —elephants and parrots — are worked into a trellis all over the body of the sari.

Odisha ikkat

Beautiful region, beautiful people. The sun temple at Konark has probably been the inspiration for the weavers to use the motifs of the wheel and the fish in most of their weaving. The weavers, especially the women, enjoyed a state of languid living, enjoying nature and life even if they lived in penury. Most of the women didn’t wear blouses but the sarees were draped so beautifully that there was no vulgarity. We often found them bathing in the river and had to persuade them to get back to their looms!

I would take the trouble of sitting with them for long hours, explaining the designs and the colours I wanted. But the next year when we visited them, they wouldn’t even have begun, and showed us some very pedestrian designs done on sarees. It was impossible to get annoyed with them… as that was the groove they had got into and this was the very reason for their poverty.

In the patola of Patan the sharp grain of the patterns emerged due to the matching of the elements of the motifs used in the resist-dyed warp and weft, whereas in the ikkats of Odisha, the grain is often not sharp, but in half-tone, as the warp and weft do not cover each other though they are resist-dyed. The Odisha ikkats do not rely on the tie-and-dye effects alone, but combine plain weaving, often with extra weft, as is visible in their sari borders and pallus. The Odisha fabrics have the wheel design in the borders and the temple spires, and in Bargarh, Sonepur and Naupatna, there are a variety of motifs like fish, birds, lions, elephants, deer, flowers, creepers and stars.

The sarees in Odisha were incredibly cheap. They had these beautiful sarees in Bargarh, in a white background, with small borders and tiny diamonds and stripes in two huge pallus. My visit to Bomkoi was so memorable as the overweave on the saree pallus looked like embroidery. The width was narrow, and a saree cost only Rs 60 at that time! I had to lengthen and widen the saree to make it wearable by attaching extra cloth, but it was well worth the trouble. Also, they lent themselves to designing beautiful garments.

If I have another wave of energy and drive, I would hit the ikkat trail once more!

Pictures by Sabita Radhakrishna

The technique

Ikkat is an Indonesian word, meaning cord, thread, knot, as well as “to tie” and “to bind”. The finished ikkat woven fabric originates from the tali (threads, ropes) being ikkat (tied, bound, knotted) before they are being put in celupan (dyed by way of dipping), then berjalin (woven, intertwined) resulting in a berjalin ikkat — reduced to ikkat.

The yarn is resist dyed in a particular sequence before weaving. When either the warp or the weft yarn is resist dyed, it is called single ikkat. When both the weft and the warp are resist dyed, and woven, it is double ikkat. This calls for considerable skill as the dyeing has to be executed with precision, and woven so that the designs interlock perfectly.