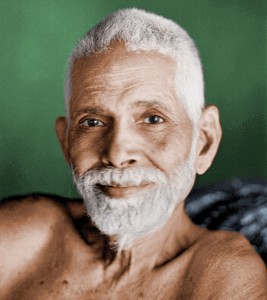

A few weeks later, I had the opportunity to visit Tiruvannamalai, a town south of Chennai in Tamil Nadu famous for its temple and for ‘holy’ personages having set up ashrams around the hill of Arunachala, popularly believed to have ‘sacred’ attributes. The most revered of these sages is Ramana Maharishi; it was to his ashram that we went. When I mentioned to Mani Sir at the ashram that my great-grandfather had been a bhakta of Ramana Maharishi and had also been on the panel of doctors attending to the Maharishi, he introduced me to John who’s been working on the archives there. John generously pulled out all the pictures featuring my great-grandfather, Dr Srinivasa Rao. When we came to a couple of pictures of him with Ramana Maharishi and a Caucasian gentleman, John said, “That’s Guy Hague. Maugham is believed to have based his central character in The Razor’s Edge on Guy Hague; and the holy man he describes in the book is certainly Ramana Maharishi.”

This information was way too exciting to ignore, nor could it be dismissed as a coincidence. It seemed more like a sign: Read the book! Find out more! Meanwhile, at the ashram bookshop, I had picked up a book with an intriguing title: The Search in Secret India by someone called Paul Brunton. The back of the book described him as “one of the twentieth century’s greatest explorers of the spiritual traditions of the East”. But what clinched the deal was that he was “also a journalist with a healthy regard for critical impartiality and for commonsense”. I couldn’t wait to get back to the guesthouse to start reading, and didn’t stop during the taxi ride back to Chennai.

It seems Somerset Maugham visited Ramanashrama and met briefly with the Maharishi.

I had not heard of Brunton, but as always, the internet yielded many answers. For starters, Paul Brunton was the pen name of Raphael Hurst and this book, first published in 1934, the year my mother was born, was a bestseller and was reprinted several times. From all accounts, it was he who introduced Indian spiritualism to the West and the West to yoga practices. The book begins: “Early travellers returned home to Europe with weird tales of the Indian faqueers and even modern travellers occasionally bring similar stories. What is the truth behind those legends… concerning a mysterious class of men called Yogis by some and faqueers by others? What is the truth behind the fitful hints which reach us intimating that there exists in India an old wisdom that promises the most extraordinary development of mental powers to those who practise it? I set out on a long journey to find it and the following pages summarise my report.”

After setting out the context by talking about his childhood and curiosity and the events that led him to embark on a journey, he writes about such different individuals as an Egyptian magician and a thought reader in Bombay; a self-styled ‘messiah’ of Persian origin, Meher Baba, near Ahmednagar, whose first ‘communication’ with Brunton via an alphabet board is: “I shall change the history of the world”; the ‘anchorite of the Adyar river’ Bramasuganandah, a yoga practitioner in Madras, whose mastery of breath control appears to even conquer death; and even the Shankaracharya of Kanchipuram. It is he who, when Brunton asks to be directed to a master who “is competent to give me proofs of the reality of higher yoga”, directs him to Ramana Maharishi.

Brunton’s description of his experience in the silence of the sage’s presence will resonate with many: “There is something in this man which holds my attention as steel filings are held by a magnet. I cannot turn my gaze away from him. My initial bewilderment, my perplexity at being totally ignored, slowly fade away as this strange fascination begins to grip me more firmly. But it is not till the second hour of the uncommon scene that I become aware of a silent, resistless change which is taking place within my mind. One by one, the questions which I have prepared in the train with such meticulous accuracy drop away… I know only that a steady river of quietness seems to be flowing near me, that a great peace is penetrating the inner reaches of my being, and that my thought-tortured brain is beginning to arrive at some rest.”

However, my mind was restless regarding A Razor’s Edge and since I was impatient to read it, I launched into it alongside A Search in Secret India. Larry Darrell is one of several characters whose lives intertwine and whose stories are told in fairly great detail in The Razor’s Edge; Maugham appears in the novel as himself. After serving in the war, Larry returns to society seemingly at peace with the world. But as the novel reveals, he has no ambition to ‘become’ somebody, he is on an inward quest. This journey takes him to different parts of the world and through different experiences; eventually he finds himself at the ashram of a holy man who wears only a loin cloth and who speaks little, but he speaks to Larry’s soul. This is a poor and imprecise précis of a brilliant novel, but it only points to the terms of reference.

Paul Brunton was the pen name of Raphael Hurst who apparently introduced Indian spiritualism to the West and the West to yoga practices.

When, towards the end of the novel, Larry tells Maugham that the “greatest ideal man can set before himself is self-perfection”, the latter reacts sceptically, saying, “Can you for a moment imagine that you, one man, can have any effect on such a restless, busy, lawless, intensely individualistic people as the people of America?”

“I can try,” replies Larry. “It was one man who invented the wheel. It was one man who discovered the law of gravitation… If you throw a stone in a pond the universe isn’t quite the same as it was before… It may be that if I lead the life I’ve planned for myself it may affect others, the effect may be no greater than the ripple caused by a stone thrown in a pond, but one ripple causes another, and that one a third; it’s just possible that a few people will see that my way of life offers happiness and peace, and that they in their turn will reach what they have learnt to others.”

What Larry’s way of life is, requires a reading of the novel, and there is no doubt that some of Brunton’s characters have caused ripples that continue to remain in play. It seems Maugham visited Ramanashrama and met briefly with the Maharishi. Surely he was influenced by Brunton’s work; after all he published his novel some ten years after A Search in Secret India. The way the two books came together for me is nothing short of a miracle.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist.