If Allah wants to sing, it would be in Bhimsen Joshi’s voice.” This, says Dr Nagaraj Rao Havaldar, the late Kirana gharana icon’s disciple-biographer, is how a Pakistani music critic paid his homage to Joshi. And every time you listen to the maestro’s impassioned rendering of Tum rab, tum sahib in the raga Brindavani Sarang, you cannot help wondering if Ishwar or Allah could be unmoved by this voice from the depth of the singer’s very being.

Yet a newcomer to the world of Indian classical music could have easily been forgiven for hastily leaving a concert hall featuring a vocal performance by the late Bhimsen Joshi under the mistaken impression that the man on the stage was a prizefighter, not a musician. The best known exponent of the Kirana gharana had over the years tended more and more to resemble one, with his exaggerated body language and facial contortions adding substantially to the impression created by his stocky, muscular build, though truth to tell, his given name suggested he was quite sizable even at birth.

The inimitable vocal music of Bhimsen Joshi was an amalgam of meditative depth, a sonorous, malleable voice, perfect laya control and absolute swara precision. He worked assiduously for decades at making the gharana his own, incorporating the influences he had sought from all the masters he admired, no matter what school they belonged to — Patiala, Agra, Gwalior or more. Which is why his unique style was characterised by a reverberant masculinity quite removed from the softer nuances of his parent gharana that had transplanted itself from Kairana in the north to Dharwar in the south, though the faster and higher pitched the taans he purveyed, the softer his voice grew.

To many faithful followers of Bhimsen Joshi’s music, his voice, even at its most resonant, had a rare intimacy, somewhat reminiscent of the effect the voices of Amir Khan or D V Paluskar had on them. Heard live, it reverberated from the stage to the last row of closed halls and open spaces alike, its sheer power captivating the audience. In recordings, its almost paradoxical tenderness never failed to suffuse listeners with a feeling of other-worldliness.

A typical Bhimsen Joshi concert during his best years was a slow awakening from a trance, deep immersion in the music gradually unfolding to give way to displays of immaculate vocalisation in three octaves, perfect control and acute sensitivity in shaping the aesthetics of the raga that he explored to the hilt. (For over a decade through the seventies and eighties of the last century, however, Joshi was a victim of alcoholism, which affected his music adversely. Luckily, he overcame his troubles through his bhakti and total surrender to a higher power.)

Joshi was born on 4 February 1922 at Gadag, Karnataka, in a Kannada-speaking family. His father, Gururaj Joshi, the headmaster of a municipal school, wanted Bhimsen to qualify as an engineer or a doctor, but the boy was music-mad from early childhood. He eventually scaled heights in Hindustani classical vocal that few could equal, emerging as one of the most distinguished products of the bilingual musical culture of Dharwar.

The tutelage under Sawai Gandharva, lasting five years, was arduous — full of menial tasks and corporal punishment typical of the traditional guru-sishya system — until Bhimsen convinced the guru of his seriousness of purpose.

His love affair with Hindustani music began when he was still a slip of a lad, as he daily stopped on his way from school at a tea stall owned by a true rasika to listen the gramophone records he played. This is where he fell in love with an oft-repeated disc of Ustad Abdul Karim Khan. He had already been exposed to devotional music as a child born in an orthodox Madhva family of kirtankars. He had also had some grounding in music guided by a certain Agasara Chennappa of Gadag.

Bhimsen’s obsession as a child with music frequently led to his disappearance from home, as he followed passing bhajan groups as if hypnotised, only to be restored to his parents by friends, sometimes even the police after he had fallen asleep at strange locations. He eventually ran away from home after repeatedly listening to an Abdul Karim Khan recording — a thumri in the raga Jhinjhoti. The ustad had been the ‘founder’ of the Kirana gharana whose disciple Sawai Gandharva was to eventually become Joshi’s guru.

Bhimsen wandered from place to place in search of a guru, mostly travelling ticketless by train. After unsuccessful visits to several cities, he reached Gwalior after three months, all along entertaining his co-passengers with songs he had learnt from gramophone records.

Bhimsen then travelled to Kharagpur, Calcutta, Delhi and finally Jalandhar, trying to learn from several great masters. One of his early mentors was sarod maestro Hafiz Ali Khan of Gwalior, while the famous film star musician Pahadi Sanyal of Calcutta was impressed enough to recommend him for acting-singing roles on the silver screen, though Joshi was clearly keen on music, not movies as a career choice. His travels took him to the annual Har Vallabh festival of Jalandhar, where he came into contact with Vinayak Rao Patwardhan. The celebrated vocalist, an exponent of the Gwalior gayaki, advised him to seek out Rambhau Kundgolkar of Kundgol — a village not far from Gadag — already famous as Sawai Gandharva, a tribute to his celestial music, or gandharva gana, paid to him by an adoring public. Biographer Havaldar says: “Panditji wrote to his father that he was willing to return home, on the condition that he must be allowed to learn from Sawai Gandharva. The parents were only too delighted to see the return of their son, and agreed to his terms!”

Though Gururaj Joshi had wanted his son to take up a proper job, he had the vision to support him in his journey seeking musical excellence. He took Bhimsen to Sawai Gandharva who subjected him to a rigorous audition before accepting him. He demanded a monthly fee of ₹25, a stiff burden on the humble schoolteacher, who also paid for harmonium and tabla accompanists for Bhimsen’s regular practice sessions.

The tutelage under Sawai Gandharva, lasting five years, was arduous — full of menial tasks and corporal punishment typical of the traditional guru-sishya system of yore — until Bhimsen convinced the guru of his seriousness of purpose. Gandharva was cruel only to be kind during Bhimsen’s intense gurukula vasa. “Though he would appear to be very strict, he was affectionate in his teaching. Every day he taught raga Todi in the morning, raga Multani in the afternoon, and raga Pooriya in the evening, strictly adhering to the time theory of the ragas.” The redoubtable Gangubai Hangal, senior to him as Gandharva’s pupil, assumed the mantle of elder sister to him, while a fellow disciple Firoz Dastur also rose to prominence.

All his life, Joshi bore a scar on his face caused by a missile his guru had hurled at him; he also remained deeply committed to his taleem and his raga music, strongly grounded in its traditional base, exhaustive, intense, deeply felt, even as his music underwent many significant changes. He accompanied Sawai Gandharva on his concert tours and also heard the recitals of several contemporary greats from all over India. His concert in Pune, on the occasion of the 60th birthday of Sawai Gandharva, in January 1946 was the starting point of his meteoric rise to fame.

Bhimsen’s obsession as a child with music frequently led to his disappearance from home, as he followed passing bhajan groups as if hypnotised, only to be restored to his parents by friends.

Joshi’s relatively limited repertoire of ragas was offset by his exquisite rendering of these ragas which he constantly reinterpreted afresh. His Todi, Darbari and Miyan ki Malhar were perennial favourites, but his Gaud Sarang, Suddha Sarang and Brindavani Sarang, his Suddha Kalyan and his thumri-s in Jogia and Bhairavi were no less enchanting. As if to compensate for his so-called raga limitation, he created a few new melodies, mainly combinations of known ragas.

A versatile, peripatetic musician (his jetsetting ways earned him the sobriquet ‘Havai Gandharva’) who blended the best of north and south in Hindustani music, he sang for the purist and lay rasika alike, taming a magnificent voice to produce flawless music. If his Sant vani and Dasarpadas were testaments to his devotion to God and the Kannada language (he even had pure Hindustani bandishes composed in Kannada), his jugalbandi ventures with Balamuralikrishna remained no more than curiosities, hardly reducing the north-south divide in Indian classical music. He, however, became an inspirational symbol of national integration with his poignant rendition of Mile sur mera tumhara as part of a televised campaign that captured the imagination of a vast populace. His film songs in Hindi and Kannada were big hits with lay audiences who knew nothing of his classical music background as well as shastriya sangeet aficionados. Madhav Gudi was perhaps his best disciple, though the vocalist never received his just deserts as a concert performer.

Panditji wrote to his father that he was willing to return home, on the condition that he must be allowed to learn from Sawai Gandharva. The parents were only too delighted to see the return of their son, and agreed to his terms!

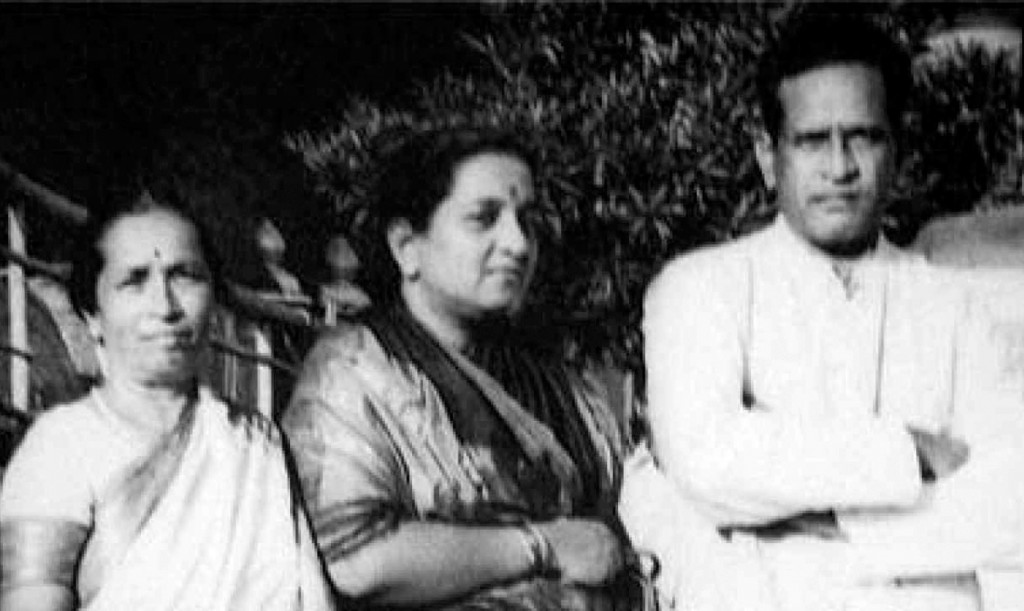

Bhimsen Joshi married twice at a time bigamy was not yet outlawed everywhere in India. He had children by both wives, Sunanda and Vatsala. “He loved fast cars and travelled at the speed of light, performing tirelessly for over four decades,” says a music critic and admirer.

The Bharat Ratna, conferred on him in 2008, was the crowning glory of his career. Amongst his major awards were the Ustad Enayet Khan Foundation Award (2002), Padma Vibhushan (1999), HMV Platinum Disc (1986), Padma Bhushan (1985), Sangeet Natak Akademi Award (1976), and Padma Shri (1972).

The writer is an author and former editor of Sruti magazine.