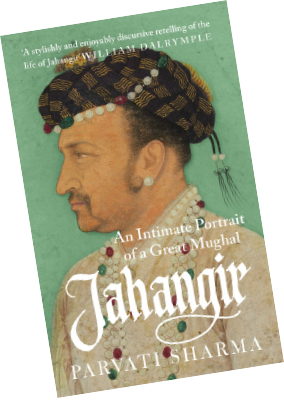

In her recently published portrait of Jahangir, Parvati Sharma portrays that he has the reputation of being a weak man, a profligate almost, at best an alcoholic with an eye for art and greed for pleasure, and one who was controlled by a powerful wife.

But in fact, far from being a disinterested prince and an insignificant ruler, Jahangir showed tremendous ambition and strength throughout his tumultuous life. When his succession was threatened, he set up a rival court in the face of the mighty Akbar himself. He was the first Mughal to win the allegiance of the Ranas of Mewar after subjugating them, a feat that Akbar had not succeeded in achieving.

In most aspects, Jahangir, the fourth Mughal emperor, was pivotal to the dynasty about which it has been said that “there never was and will never be another age quite like the Mughal. Everything about it was big, larger than life, extravagant. From the majesty of the Emperor to the pomp of the Imperial Court, from the splendour of its architecture to the sublimity of its art and music, from debauchery and cruelty on an unprecedented scale to wisdom and tolerance rarely exhibited before, from the prosperity it engendered to the anarchy it left behind, in the history of the world, the Mughal Empire is rivalled only by that of the Roman.”

Parvati depicts Jahangir as an astute ruler, a conscientious administrator, a keen observer of societal arrangements and the dynamics of social change in the world around him, a large swathe of which he ruled. He was a man deeply interested in the world of nature which was depicted in his amazingly beautiful atelier, the paintings of which have never been matched in Medieval history. This book attempts to correct a grave historical wrong to one of the greatest rulers in history who has been much undervalued.

Aesthetics apart, consider the fact that during the reign of Emperor Jahangir, the annual imperial income, according to the author, was a mindboggling 56 million pounds. By comparison, Jahangir’s contemporary on the British throne at that time got only half a million pounds per annum from the British treasury. The imperial revenues of the Mughal empire mirror the stable prosperity and administration of India. Also, relative peace in the provinces under Mughal rule resulted in an unprecedented blossoming of arts. Apart from being notorious for his alcoholism as he was well-known for his refined aesthetics, Jahangir was also a just personality whose empire represented secular harmony. He also gave us gardens with exotic fruits and flowers, hitherto unknown to India.

The author also gives us details about the dietary sensitivities of the imperial Mughals. The royal family was addicted to fine fruits, much of which were imported from Afghanistan, Chaman and Yazd. Jahangir and Nur Jahan rejoiced in the watermelon, pomegranate and grapes that always trailed the imperial camp through the length and breadth of the vast Mughal domain.

Jahangir derived pleasure from the beauty of nature. Travelling through a vale of oleander flowers in bloom, he ordered everybody to decorate their turbans with oleander bouquets. Anyone who didn’t would forfeit his turban. Once, when he caught a dozen-odd fish in one throw, he released them into the water, with pearls pinned to their noses!

From the flower-bedecked nobles and the bejewelled fish, one might imagine an emperor either whimsical or effete, childlike, depending on one’s perspective and inclination. If his memoirs comprised such anecdotes alone, the debate about his character too might have remained at this somewhat insubstantial level. But this was not true.

He was an emperor of the most powerful empire of the time. He was powerful in a way that may be impossible to imagine today.

This intimate portrait of Jahangir shows that the Mughal empire reached its meridian during his reign in terms of economic prosperity, aesthetics and splendour, well-being of its people; military might and invincibility, and the secular interaction of different communities. This book recalls an India which was religiously tolerant, reasonably open and pluralistic. Parvati’s book resurrects Jahangir from the annals of debauchery and opiated hedonism.