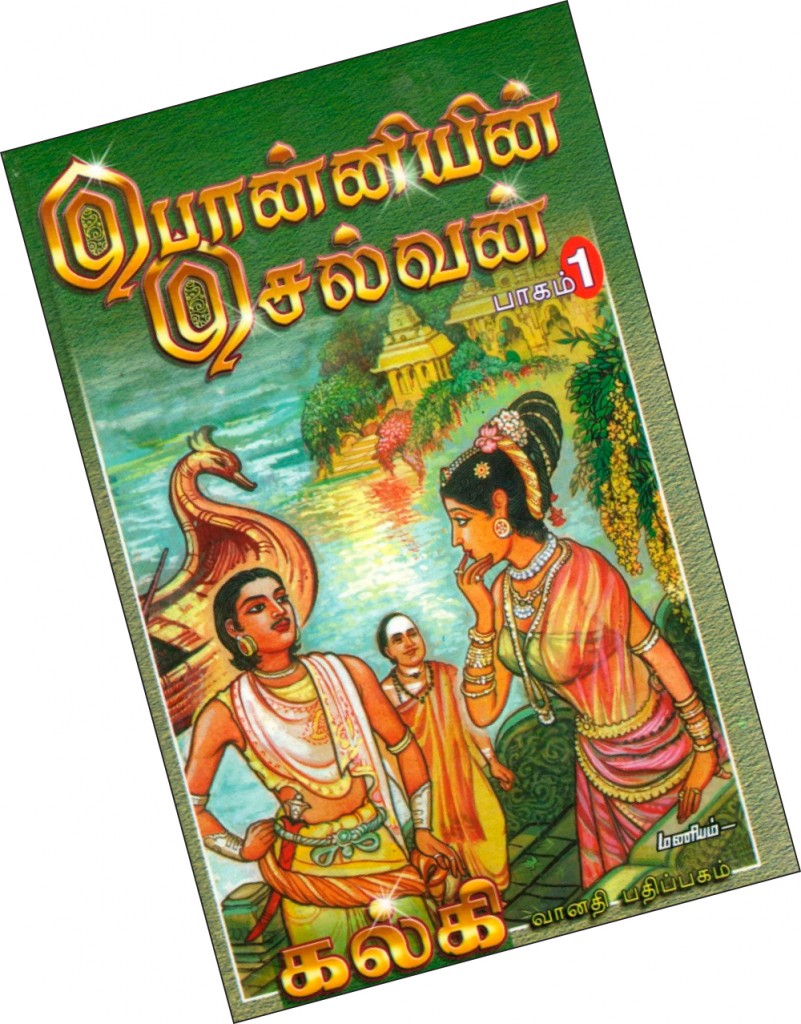

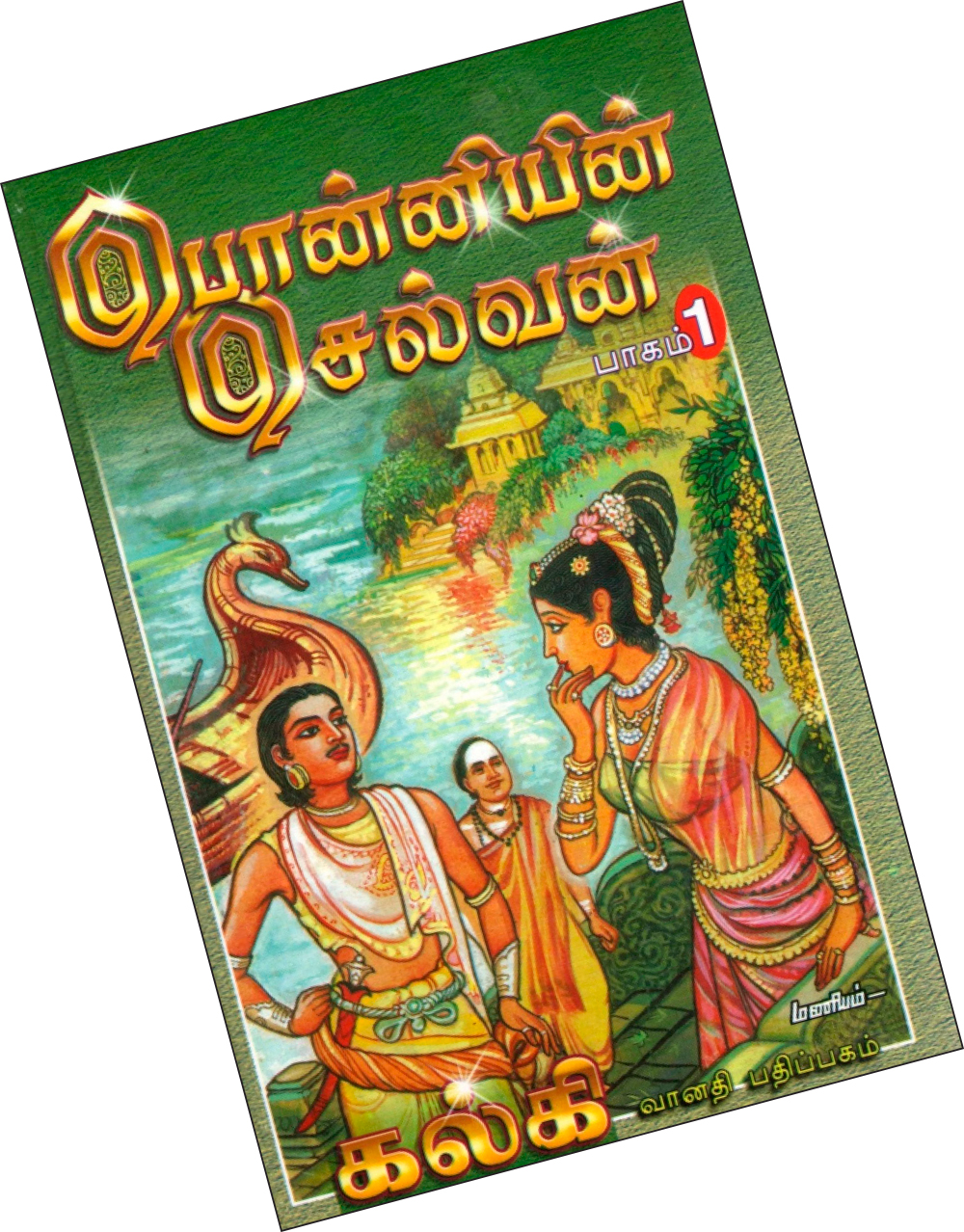

Before Ponniyin Selvan was a film, it was a book in five parts, and before it was a book, it was serialised in a Tamil magazine called Kalki, starting October 29, 1950, concluding May 16, 1954. Kalki was a magazine started by Kalki. And Kalki was the nom de plume of R Krishnamurthy, a writer and editor of amazing virtuosity, a freedom fighter with a passion for the Tamil language. At various times he signed off under various pseudonyms such as Agastyar, Tamil Teni, Ra Ki and Carnatakam. But the one that stuck was Kalki. As to why he chose Kalki, there are several theories and no solid answers.

But before we get into all that, there’s a small piece of wonder I’d like to share. As happens so often, this time too, the ‘universe’ threw into my lap a gift connected to the subject of this column: a two-volume, hardbound book set titled Kalki Krishnamurthy, His Life and Times by Sunda, M R M Sundaram, translated into English by Gowri Ramnarayan, Kalki’s granddaughter! In the very first pages of this elegantly produced offering from the Kalki Biography Project lie some clues to the ‘Kalki’ mystery. So, to get back…

According to S S Vasan, founder of the Tamil magazine Ananda Vikatan and of the film production company Gemini Studios, Kalki first used this pseudonym in an article for the magazine way back in 1928. At a time when verbosity was seen as the hallmark of ‘good’ writing — indeed, it sometimes still is — Vasan wrote about that piece in 1954 that Kalki had ‘adopted a style that even a child could understand. It sprang from deep thought and provoked laughter’. Thereafter, the ink in Kalki’s pen never dried and, 13 years later, he founded his own magazine, Kalki.

Kalki had adopted a style that even a child could understand. It sprang from deep thought and provoked laughter.

– S S Vasan, founder of Tamil magazine Ananda Vikatan

While one theory is that the pen name derived from the tenth avatar of Vishnu, Kalki, supposedly signifying change through the discarding of old, outmoded conventions, another recalls a talk that Kalki himself gave in Colombo in 1950 where he apparently said that he had shortened his name because Krishnamurthy was difficult for some people to say. Yet another theory links the ‘kal’ part to ‘Kal-yanasundara Mudaliar with whom I studied Tamil, or from the town Kal-lidaikurichi, where I was born’ or even to Kalyani, supposedly his wife’s name (it was not!).

Kalki packed in a lot in a comparatively short lifespan of 55 years. Apart from being a prolific and widely read writer, he participated actively in the freedom struggle, opposed antediluvian customs and practices, and was a champion of the Tamil language. He wrote articles, short stories, novels; his Alai Osai (Sound of the waves), with the freedom struggle as its backdrop, won the Sahitya Akademi award in 1957. Best-known, possibly, are his historical romances: Parthiban Kanavu, Sivakamiyin Sabatham and Ponniyin Selvan. All these were first published in magazine instalments and later as books. PS comes in five parts. The C V Karthik Narayanan translated version from Macmillan, has The First Floods, The Cyclone, The Killer Sword, The Crown and The Pinnacle of Sacrifice.

There are many English versions and at the moment I am listening to the audio of Book 1: Fresh Floods translated by Pavithra Srinivasan whom we sadly lost in June 2021. This rendering by Amit Bhargav is engaging, the Tamil words are spoken clearly, and the translation seems to reflect Kalki’s prowess as a storyteller, keeping in place his vivid descriptions, sharp conversations and flashes of humour. Just for the heck of it, I listened to ‘Chapter 31: Thieves! Thieves!’ while simultaneously following the text in the book. Remember, the book version is Karthik Narayanan’s translation and the audio is Pavithra Srinivasan’s. I discovered that the audio was far more detailed than the book, which could mean one of two things: either that the former is an embellished version of the original Tamil or the latter is a pared down one. Since I have only rudimentary Tamil reading capability, I will have to get someone to check this out.

In an interview with Anjana Shekhar in The News Minute in August 2018, Pavithra Srinivasan speaks about being introduced to ‘the cult series’ at the age of 12 by her mother and being instantly hooked despite stumbling a little over names such as Chinna Pazhuvettarayar, Irattaikkudai Raajaliyaar! ‘A translator is giving a part of themselves to it (the work),’ she points out. ‘Only the translator knows what the original source is. Therefore, the readers trust the translator to give them the most accurate, rich experience,’ she says, adding that the best compliment is to hear a reader say, ‘I am so happy with this translation, I don’t feel like reading the original.’

My friend from the book club didn’t read the original, she did something else. Married at 18, she said one of the first things her 14-year-old sister-in-law asked was, ‘Have you read Ponniyin Selvan?’ It was being serialised in Kalki at the time — in fact, it’s been serialised several times in the magazine because it was so popular and newer readers were being added to the ranks of its subscribers. My friend, although a Tamilian, had grown up in Bangalore, so she couldn’t read and write Tamil. So, the 14-year-old took it upon herself to read aloud/tell the story to the 18-year-old! That was her exposure to PS! How family members would vie with each other to be the first to grab the magazine in order to catch up with the latest instalment of whatever was being serialised is the stuff of Kalki legend.

What was so special about Kalki’s writing that he continues to be remembered and read to this day, that newer translations continue to be published? Karthik Narayanan’s version has an introduction by T Sriraman from CIEFL, Hyderabad, that’s not in the style of a hagiography, it’s an objective analysis of the writer and offers a context for his historical fiction. Interestingly, he refers a great deal to Sunda’s work on Kalki, in the original Tamil. In answer to the question as to what makes Kalki’s historical fiction tick, he quotes Prof Meenakshi Mukherjee as observing that ‘in many languages the most popular themes of historical novels centred around Shivaji and the Rajput kings who successfully resisted Mughal power’, and clarifies that ‘Kalki found no need to look outside Tamil Nadu for true tales of heroism’. He goes on to say: ‘Kalki’s acknowledged achievement as a writer consists in a transformation of Tamil prose style into a medium eminently suited for discourse — literary, political, even historical — in the modern world. In fact, Kalki had to rescue the Tamil of his day from its votaries as well as its detractors. … Among the writers of Tamil there were two kinds: those engaged in religious writing who wrote a highly Sanskritized, and therefore incomprehensible variety, … and secondly, those fanatical purists who assiduously avoided any trace of Sanskrit but who in the process inflicted the most stilted kind of style on their readers and listeners. (These people called their Tamil ‘Sentamizh’ — high tamil — but Kalki described it as ‘Koduntamizh’ — cruel Tamil!) Kalki steered clear of these extremes.’

Anybody who knows Tamil will understand the paradox and appreciate Kalki’s refreshing approach which, some 80–90 years on, remains relevant. That, perhaps, is his lasting legacy.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist.