Shashi Tharoor is a mesmeric speaker and prolific writer (he brings out a book every year) as everyone knows, but his fondness for big words is a myth. Good communication in speech or writing is a matter of using the right word, as Tharoor has said often.

A big word is justified only if it’s the best one for the occasion. Otherwise it looks absurd and pompous, like a person wearing a three-piece suit for shopping in a bazaar round the corner.

However, Tharoor’s wordsmith reputation led to a request from Penguin India for a book titled Tharoorosaurus, which covers three words — Tharoor, tyrannosarus (because “people are terrified of big words”) and thesaurus. Tharoor clarifies that the book isn’t a scholarly work but reflects his love for words, which he inherited from his father Chandran Tharoor. There was no word game at which his father did not excel, whether it was Scribble or Bingo or games that he devised himself.

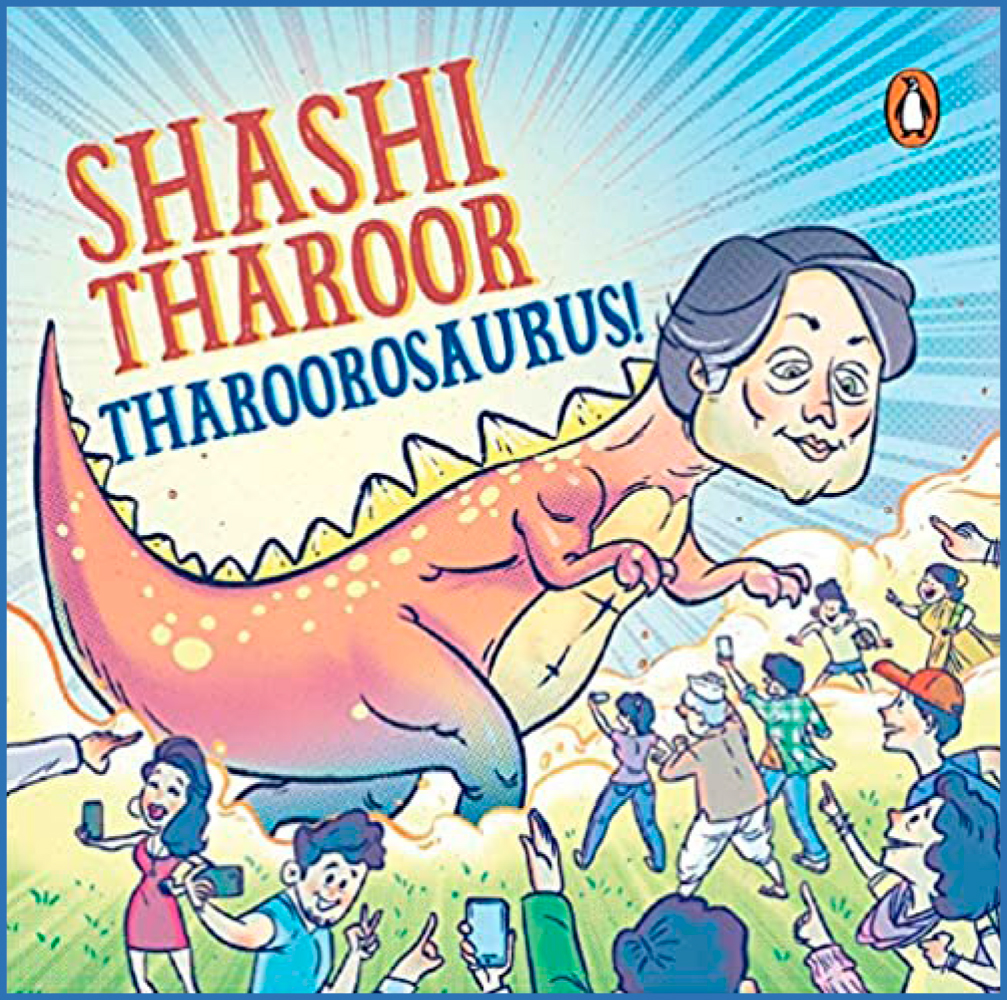

The book describes and analyses 53 words: there’s a definition for each word, a sample usage and a little essay. Plus a one-page fun sketch. The cover shows Tharoor’s head on a long dragon’s body.

The cover and the sketches inside fascinated my four-year-old grandson. He took the book away from me before I could read it, opened its pages again and again over the next couple of weeks and stared at the sketches, and asked me to “explain”. By the time he was through with the book and agreed to part with it, its cover had come off and the pages began to look frayed.

The book begins with the horrendous-sounding Agathoka-kological which means “consisting of both good and evil”. The word was coined by English poet Robert Southey in the early 19th century. Tharoor says Indian philosophy has often held that good and evil can coexist in the same person. The heroes of the Mahabharata were god-like, yet not perfect human beings. They were prone to lust, greed and anger.

The longest word in the book is Floccinausinihilipilification which means “the act of estimating something or someone as worthless”. Sir Walter Scott in 1826 said the inventor of the word was William Shenstone who used it in a letter in 1741. Perhaps one could describe a book, a movie, a theory or a budget as an exercise in Floccinausinihilipilification.

Contronym is an interesting word “which can mean the opposite of itself”. Tharoor cites the example of President Trump’s “sanctions” on Iran’s oil supplies. Sanctions is a contronym because it means both “permitted” and “prohibited”.

The book features common words like apostrophe, brickbat, curfew, impeach, jaywalking, pandemic, phobia, lunacy, lynch, quiz, quarantine, hyperbole, namaste, umpire, yogi, zealot. There are less familiar words like aptagram, authorism, cwtch, cromulent, defenestrate, panglossian, epicaricacy, epistemophilia, lithologies, rodomontade, snollygoster, valetudinarian and zugzwang.

Have you heard of the word Cwtch which just means a hug? You are Panglossian if you are foolishly optimistic. Epicaricacy is deriving pleasure from the misfortunes of others. On the familiar word hyperbole, Tharoor quotes American humourist Will Rogers who said of a particular politician that if brains were gunpowder, he wouldn’t have enough to blow the wax out of his ears.

In sum, this is a fun book, particularly if you are a word-lover.

The author is a senior journalist and a member of the Rotary Club of Madras South.