Such was the enigmatic aura and majesty of the 150-year-old civil service in India that in the 1970s, at the St Stephen’s College in Delhi, we wrote the competitive examinations, almost as a Pavlovian response. For no other career recommended itself to us, or our forebears, as worthy of serious consideration.

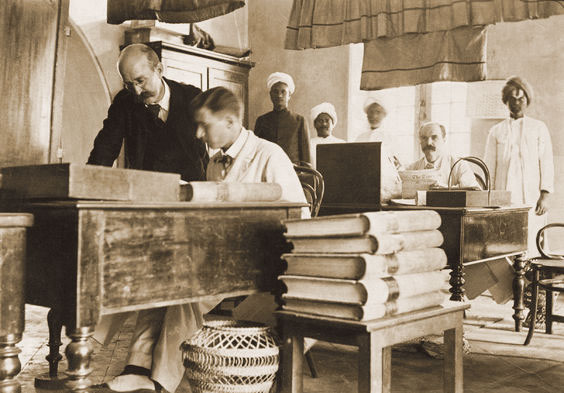

Many of us find it difficult to juxtapose in a coherent fashion puzzling reminiscences of the ideals and ideas with which we set out for a career in the IAS. But here I have tried to etch sepia portraits of the ICS (Indian Civil Service) officers… the men who ruled India, and systematically created her administrative structure for a century and a half.

One may recoil at the thought of the British rule but old-timers are unanimous in their recognition of the many-splendoured contribution of the civil services to the Raj. The ICS was an incisive, stable and dynamic instrument that maintained peace and facilitated civilian rule to take root in India. The service was the steel frame that held together a disparate empire with uneven levels of economic and social development, and later, the largest democracy in the world.

(First Election Commissioner of India).

Punjab’s canal system

In the Punjab, the Lawrence brothers gave to this hardy frontier province an irrigation system and canals upon which the most modern agricultural infrastructure could be built. Unto the last, the ICS contribution is reflected everywhere. In Chandigarh, M S Randhawa conceived the renowned Rose Garden with its rare illusions of pine forests and sloping landscapes leading to hidden waterways. Randhawa’s collection of miniature paintings from Kangra, Guler, Basholi, Chamba and other hill kingdoms were gifted by him to the Chandigarh Museum. A N Fletcher of the ICS is best remembered for having created a lake for Chandigarh and the speed with which this sparkling water body enriched the new city under his draconian supervision.

The Commissioner would sleep by the river at night and noted a booming sound that he described as ‘the Teesta Guns.’

Till 1947, the civil servant was in evidence everywhere. It was the ICS that comprised the higher judiciary. Civil servants were posted as District Judges and District Magistrates. From the same stream came Judicial Commissioners and Political Agents to the princely states. Also, ICS men went on to the Foreign Service to serve as India’s ambassadors to foreign lands.

Impeccable honesty

The ICS men would not freely mix in society. They were retiring in nature and spurned entertainment. They were keen gardeners, equestrians, historians, scholars, poets, authors, musicians; of philosophical disposition, interested in archaeology and history, nature and, the nature of things. They were generalist administrators who quickly absorbed matters within their administrative jurisdiction and gave a visionary direction to the specialists posted under them. They were men of impeccable honesty. Thus the Nazir of the Deputy Commissioner’s office too commanded great respect as his tonga passed through the bazaar to place substantial orders on a promissory note for blankets or jerkins on a cold winter night, on behalf of the Department of Relief and natural disasters.

Important Gazetteers

Before 1900, an ICS officer took upon himself to study the nature of River Teesta in Northern Bengal. In his gazetteer, the Commissioner described in over one hundred pages the river’s ‘moods.’ He would sleep by the river at night and noted a booming sound that he described as ‘the Teesta Guns.’ He indicated that whenever the guns resounded, disaster followed in the northern areas, Jalpaiguri district in particular. Much later, in the Sixties, a great flood devastated large tracts of land, taking its toll on hundreds of lives, notwithstanding the Flood Protection Commission headed by top-ranking engineers. Had someone turned to the gazetteer, the requisite precautionary measures could have been taken well in time to save the beautiful town and undulating forested areas. Indeed, the gazetteers written during the British period and soon after Independence, are a compendium of knowledge, but unfortunately very few IAS officers have the inclination to turn to these anymore!

Eccentric too!

The British ICS officers were not without their eccentricities. The Divisional Commissioner mentioned above, is said to have silhouetted his confidential assistant with silver cutlery knives, over his evening whisky and soda, after which the Commissioner would drive home the shaken clerk in his Rolls late in the night! The knives would be sent for repair to Calcutta with the same assistant the next morning, who, in turn, would visit the Kalighat temple to seek divine blessings, all on the personal account of the Commissioner Bahadur!

The ICS officers were men of steel, unflinching in their loyalty to Her Majesty and dedicated to giving the fruits of peace and good governance to the people of India. No one dared question the Sarkar. Four elephants stood at the Commissioner’s gate raising their trunks and trumpeting in salutation each time the Sarkar exited or entered.

The ICS officers were men of steel, unflinching in their loyalty to Her Majesty and dedicated to giving the fruits of peace and good governance to the people.

The civil service had perfected the art of administration and the British rulers were conscious that the texture of administration must always be civilian. They realised that a State based merely on uniformed strength and show of arms could never progress and give good governance.

The District Magistrate did not use red lights or sirens on official transport vehicles. He toured on horseback, in open jeeps, on bicycle and foot from one rural area to another to meet villagers at their convenience and to dispense justice from under the village tree. He was known to be above board. He fully identified with the sorrows and problems of rural India and endeavoured to find practical solutions. His justice was based on reason and incontrovertible logic.

Often, this officer would disguise himself and walk in the native bazaar to enquire if there was tyranny at lower levels in government. This had its concomitant comic sequels. A judicial commissioner in the Central provinces himself assiduously typed out and sealed all important Dak late at night. Before turning off the lights, he would arrange for a cobra to be placed in a round wicker basket, above the dak pad, till work commenced from the camp office, next morning!

The ICS men were clear and confident. With understated humour, an incident has been recounted about a Chief Secretary of the Punjab who was petitioned by an agitated contractor. He was given the task of building the Chandigarh Secretariat, but the lower staff in the finance department were playing cat and mouse in releasing funds. The Chief Secretary, then out for his evening constitutional, heard the man’s complaint, and wrote out on an empty cigarette packet an order releasing Rs 5 lakh for accelerating the pace of construction of the Secretariat!

Magnificent contributions

Some of the magnificent contributions of the civil service during the Raj are the Indian Railways; the Indian Penal Code; the Code of Criminal Procedure; the Indian Evidence Act, the Jail Manual; the concept of District Administration; the irrigation system; the Grand Trunk Road; the Indian Army and the defence services. Add to these an organised police force, and systematised educational and judicial systems.

After 1947, the civil service was confronted with a situation that had altered in terms of power equations. While the ICS continued to exercise control, they now did so under a new political dispensation. Leaders of the genre of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad, Sardar Patel, and so on, were themselves erudite scholars with a lifetime’s experience in fighting for India’s independence. They recognised in the civil service an invaluable, perhaps the finest, instrument for developing the country. And, therefore the relationship between the political government and the permanent executive was largely harmonious.

However, with the passage of time politicians quickly realised that to remain in power, they would have to cater to unceasing, often unreasonable, demands of their constituents which required cutting short procedures.

Short cut methods

The short cut methods contributed substantially to the breaking down of a system of administration that had established its credibility for well over a century. The reaction of the civil servant was, at first, to become more rule bound, and then to concentrate on self preservation. It had to be so, for the politician wielded the power of transfer, and humiliate.

The imperatives for remaining in office could no longer be the high ideals that guided the independence movement as far as the politician were concerned and, no longer of giving just and objective administration to India, as far as the civil servant was concerned. The democratic processes opened up a new set of regulations.

In line with the policy of short cuts, politicians realised that it is easier to deal directly with the police rather than through the civil servant who by law is in charge of the police force. Thus the police gained, lopsided significance in many states, while the civil service took to waiting and watching.

The higher judiciary, earlier manned by ICS officers, to a large extent, was denied to the successor service. With abolition of princely states, the political department to which civilians were deputed as Residents or political agents, was wound up while the IFS gained for itself an independent identity.

Over the years even the quality of entrants in the civil services has deteriorated and today IAS officers have to function in a dramatically changed administrative situation and are successors to the men of steel, only in a manner of speaking. The political climate has changed and the Magistracy has all but lost control over the police force. The Secretariat, though still powerful, is besieged from all sides.

And, it seems strange to recall that the last ICS Chief Secretary of Bengal approved government proposals with the inscription of a single word: Bengal.

(The writer is a retired IAS officer and author of the book: And What Remains in the End: The Memoirs of an Unrepentant Civil Servant).

Truly mai-baap

The British colonial administration, unlike the French, was known for its capability rather than perversity or tyranny. The District Magistrate was the Mai-Baap. There are touching stories about the faith people reposed in the machinery of the government at different levels. An illiterate old traveller on a train had thrown his railway ticket out of the window. In his mind, the transaction of buying the ticket and entraining for his destination had been completed. When the ticket inspector tried to extort money, the hapless villager ran out of the train at the next station, straight to the house of the District Magistrate, well past midnight, to be saved. Such was the faith of the people in the Administration.