Be part of an extraordinary, immersive experience of living in harmony with nature, and observe the consequences of mindless development.

Many years ago, I read a short story by Saadat Hasan Manto, whom many believe to have been the subcontinent’s shining literary star in the early 20th century, called ‘Toba Tek Singh’. Inspired, I tracked down an audio version in the original Urdu and was further blown away. Set in the time of Partition in an asylum for the mentally disturbed, located in what is now part of Pakistan, it examines the impact of that momentous division upon the inmates, focusing on Bishen Singh, who hails from the village of Toba Tek Singh. He’s been incarcerated for 15 years and has been mostly silent all this time, but when it is decided by the authorities that the inmates too will be divided up, with Muslims going to a Pakistani asylum and Hindus and Sikhs to an asylum in India, Bishen Singh has only one question: Is Toba Tek Singh in India or Pakistan?

This inadequate precis of the short story fails to reflect the nuances and insights that Manto lays out. My request to you, dear readers, is: Please look for the story and read it. You will find it online. I have it in print, in Penguin’s excellent series on cities, this one called City of Sin and Splendour: Writings on Lahore. This version has been translated by Khushwant Singh, who began as a lawyer practising in Lahore, and grew into a maverick journalist, writer and chronicler, known for his most famous novel, Train to Pakistan. He successfully edited The Illustrated Weekly of India, and wrote a hugely popular column called ‘With Malice Towards One and All’.

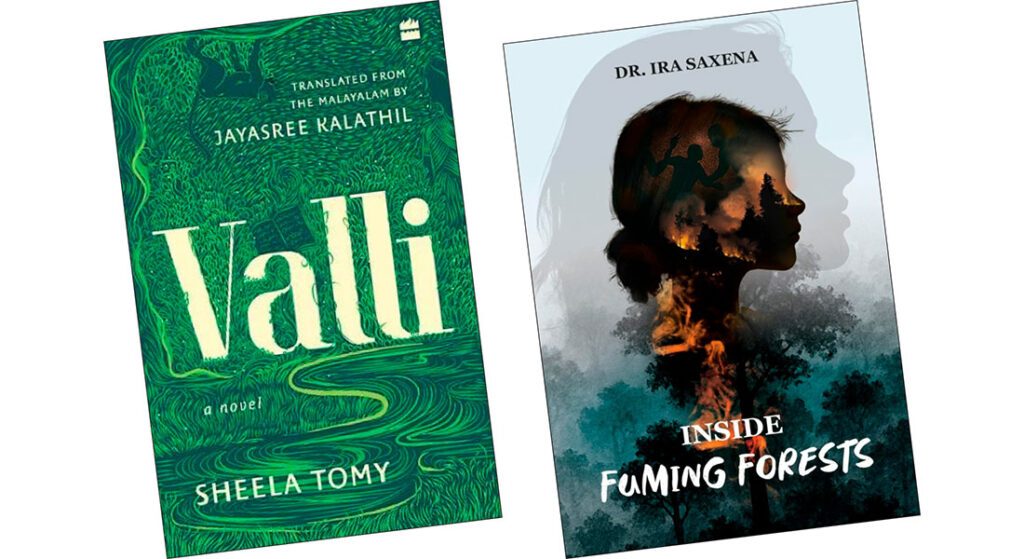

The reason for remembering this story is the book I want to introduce today, originally in Malayalam, called Valli, by Sheela Tomy, translated by Jayasree Kalathil. Read what writer Nilanjana S Roy (author of the brilliant The Wildings) says of the book: “… it is a soaring and unforgettable song of the earth, a magnificent and wrenching story of four generations in Wayanad, but also a book shot through with the murmuring, stifled but always resurgent voices of the forest and the land itself.” Another award-winning writer, K R Meera (author of Hangwoman, Aarachar in Malayalam, much lauded in both languages) calls the translation “lush and luxuriant”. Valli, in Malayalam, has multiple meanings: land, plant, young woman, and daily wages, and is used by the author as a metaphor for Wayanad itself, today a popular tourist destination in Kerala.

The book was recommended by a friend whose opinion I value, but for some inexplicable reason, it took a couple of attempts for me to get started on it. But once into the novel, I couldn’t put it down. Somewhere along the way, the connection between humans and the earth, delineated so vividly, helped me begin to understand, actually palpably understand, the connection that human beings, actually, all living things, have with the idea of ‘home’. That’s when ‘Toba Tek Singh’ flashed in my consciousness and I re-read the story.

Valli begins with a teacher-couple coming to Wayanad (then known as Bayalnad or Vananad) to settle and live among the indigenous people whose lives are interwoven with the forests and ferns, the flora and fauna, and the ways of the natural habitat. Over time, there are changes that take place that shape and shake up humans and nature alike. This, to put it simplistically, is the foundation upon which the world of Valli is built. But of course, as in life, so in this novel, there are layers and layers that unravel as the story unfolds over a few generations until the region becomes the tourist attraction it is today, reflecting so-called development and prosperity for the inhabitants, mostly settlers from elsewhere, and comfort and conveniences for visitors.

The plan to turn the Andaman and Nicobar Islands into a strategic hub echoes Valli’s warning — that unchecked development can destroy both a fragile ecosystem and its people.”

The story is told through the diary entries of Susan, the daughter of the teacher-couple, revealed as her daughter, Tessa, reads what her mother has written. Time flits between the past and the present, even as the narrative switches between myth and reality, tangible and intangible, human and natural existence. We are familiar with the term ‘magic realism’ in literature, commonly associated with writers from South America. Valli could well carry that label, except that the Wayanad it conjures up is full of magic even as it is implacably real. The writing is luminous, lyrical, and every experience is felt, by writer, translator and reader — or so it seems. I know that I couldn’t put the book down once I got into.

However, such a book may not be an ‘easy’ read, even for hardcore bookworms. For instance, a friend who downloaded Valli on her Kindle the moment I recommended it — and she is a bookworm that burrows deep and constantly — was ready to give up after about 200 pages. “I don’t understand!” she said, when she called to discuss the book, and asked what she was missing, seeing that I had enjoyed it so much. That’s the thing about those who love books: they don’t give up, they want to know what, why and how. They don’t let personal likes and dislikes subsume them.

After we had talked about it for a while, we decided that maybe one thing to do was to read up a couple of well-written reviews of Valli. Not for the synopsis, but for a sense, for clues, for direction. Then, maybe to allow the book’s narrative to lead the way, and not look to plot the action. “Yes, maybe,” she said. “I tend to look for clarity in the plot.” She decided to give it another go after a while, and not worry about a clearly defined plot. I hope now that she has decided not to try and control her reading, but to allow the world created in the novel to control her, she will begin to enjoy the experience.

And, out of the blue in the curious way in which serendipity strikes, I received a recommendation on WhatsApp from someone who has never made a book suggestion before: Inside Fuming Forests by Ira Saxena. It is set among the sal forests of Bastar and, going by the blurb, is an adventure set in the midst of exploitation of nature. I think it’s primarily intended for young readers and is, in that sense, likely to be different from Valli. However, another young adult book that came to mind is Oonga by Devashish Makhija (‘A Sense of a Meaning,’ Wordsworld, November 2022), a hard-hitting critique of the exploitation of natural resources and indigenous peoples. The more obvious connection, though, is with Abraham Verghese’s The Covenant of Water (‘A Solid, Absorbing Read,’ Wordsworld, July 2023).

We need look no further than the project to develop the Andaman and Nicobar Islands into a strategic and economic hub, plans for which are well underway, to realise that Valli hits right home. Everyone knows that such a project will destroy the ecosystem of the region and the existence of the inhabitants, both irreplaceable. Valli may be fiction, but, as one of the characters in the novel says: ‘Stories contain more truth than histories. … Because storytellers are bound to bring the truth in their heart to the story they tell. It’s different for historians. They are obliged to side with the vested interests of those who make them write those histories.’ Something we may think about.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist