Everything different yet everyone connected. Three books, indeed the best books, show us how.

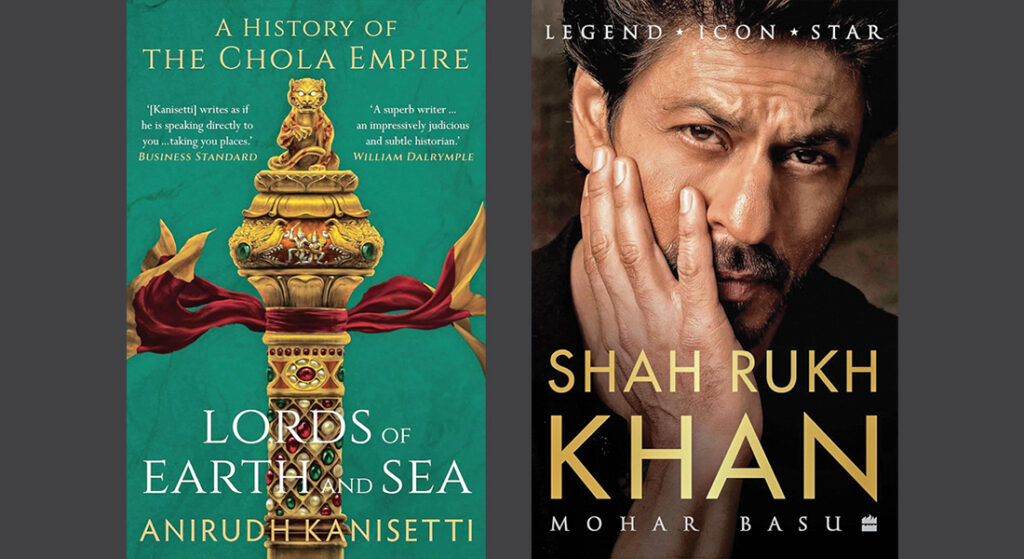

What’s common between Shah Rukh Khan, the Cholas, and three women from the Depression-era US? To discover this, you will have to dive into Legend Icon Star: Shah Rukh Khan by Mohar Basu, Lords of Earth and Sea: A History of the Chola Empire by Anirudh Kanisetti, and The Boxcar Librarian by Brianna Labuskes — biography, history and fiction respectively. However, you will be amazed by the number of similarities across the eras, starting some thousand years ago, through the early-to-mid-twentieth century, and in the present time. And, of course, the badshah is SRK, the badasses are the Cholas, and the books reference a library on rails that reached mining communities in Montana, US.

I picked up the SRK book at the Kempegowda Airport, Bengaluru, and, as with anybody reading about celebrities, the first thing I looked for were photographs, of which there are lovely ones. Sadly, though, the photographer, Pradeep Bandekar, passed away before the book could be published, but his son, Prathamesh’s words, pithily sum up his connection with SRK: “I never fully understood my father’s enduring love for Shah Rukh Khan. I would often joke: ‘You have more pictures of him than you have of me!’ It was only after his death that I was able to make sense of his bond with Shah Rukh when the actor spoke at my father’s prayer meet: ‘Pradeep was one of my first friends in the film industry. When he took my first photograph, I felt like a star…’”

Usually, much of Bollywood-related stuff has a ‘North India’ bias; happily, the author of this book, although based in Mumbai, and chief correspondent (entertainment), Mid-day, the book has a Kolkata slant, with many of her primary sources being Kolkata-based. That only goes to underline SRK’s cross-country fan base. Mohar Basu says that she has always been surrounded by SRK fans, starting with her mother, which brings to mind my mother’s observation as we watched an episode of Fauji together back in the 1980s. Watching SRK in it, she said: “This boy is special. He will go far, mark my words.” While you could say the book is a love song to SRK, it also examines his career, serial by serial, film by film, while reiterating his commitment to fans, entertainment and respecting women.

So, then, the badasses! The political dispensation today is all hands on deck promoting the idea of one India, one people, one language, one cuisine, one everything. It’s a fact, though, that whenever ‘Indian history’ is told, it largely contains north of the Vindhyas and the Mahanadi. Travel south, and you have the Rashtrakutas, the Chalukyas, the Kadavas, the Cheras, the Pallavas, the Pandyas, the Hoysalas, the Irukkuvels… lording it above all of them are the Cholas.

Historian Anirudh Kanisetti sets out to unravel the Chola dynasty which, at one time went as far north as Bengal and the Ganga while at the same time dominating the Deccan, the Cauvery plains and what is now Sri Lanka and the Malayan peninsula. And if you were of the opinion that the Cholas had a mighty navy, you would be wrong. It was trade and merchant ships that took the name and fame of southern rulers across the oceans, and even built temples in their name.

“A major theme of this book,” writes Kanisetti, “is that Indian kings were not kings in vacuums, they had to constantly prove their power, their right to be obeyed. This was true for all civilisations, and India was no exception. … Chola kings, having risen to rule over a land of vigorous regional collectives, had to campaign not just militarily but politically and, just like contemporary politicians, they found that temples were excellent sites for political advertisements…” The case in point is the mighty Rajarajeswara or Brihadeeswara temple in Thanjavur, at one time next in size only to the Pyramids of Egypt. Defying the typical history book that weighs the reader down with names, dates and other ‘bore stuff’, here, Kanisetti’s descriptions, details, anecdotes and style of presenting dynasties, lineages, battles, conquests, strategies… all of it is meticulously researched, presented with objective relish that combines amazement and wit, and is really easy to read. Nor does he omit the major role played by women who, even if they were not rulers themselves, wielded tremendous power and influence.

What was the major channel of their influence? Temple-building! Kanisetti explains how the iconic dancing Nataraja came into prominence, thanks to Sembiyan Mahadevi, the consort of Gandaraditya (949–957), a predecessor of the most famous Chola ruler, Rajaraja Chola I (985–1016). Mesmerised by the wild dancing figure of the deity in bronze at Thillai, now known as Chidambaram, Sembiyan Mahadevi ensured that a stone sculpture of the deity she called Adavallam, expert dancer, was consecrated at a temple she commissioned to be built at a place called Nallam. The rest is history. Kanisetti notes that “The ascent of Sembiyan Mahadevi was the ascent of Nataraja. And it marked the emergence of a new Chola world empire.”

What was the defining feature of Chola imperialism? “The Cholas certainly established and maintained new centres through conquest, and generally preferred Tamil-style institutions. But they were not at all interested in wiping out older cultures. Such a concept was quite alien to the Indian Ocean world, which thrived, in fact profited, from diversity. Chola imperialism added new elements to an already diverse mosaic, and offered new opportunities to Chola collaborators — whether islander or mainlander. Polonnaruwa (in Sri Lanka) soon became a bustling little town, a military and trading outpost. It was home to Lankans (both island Tamils and Sinhala speakers), as well as mainland Tamil merchants, artisans and priests.” Kanisetti reminds us of the creativity, imagination, daring and influence of the Cholas in words and images that are entertaining as well as enriching.

You will be amazed by the number of similarities across the eras... the badshah is SRK, the badasses are the Cholas, and the books reference a library on rails that reached mining communities in Montana, US.

Enriching lives with books was a librarian called Ruth Worden in Missoula County, Montana. She, along with another woman whose name has been lost to us, founded the Lumberman’s Library in a hotel for the use of workers. She approached a man called Kenneth Ross of the Anaconda Copper Mining Company to help build the collection. He liked the idea, but worried that books would give the workers ‘strange’ ideas — perhaps of freedom, liberty, choice and what have you! In any case, he supported Ruth Worden and her partner, and when he saw that the programme worked well, he enabled the building of a boxcar or bogie with shelving to house the books. And so the books travelled by train to readers all along the line!

Inspired by this story and the presence of the original Lumberman’s Library boxcar in Fort Missoula, Brianna Labuskes wrote The Boxcar Librarian in which she brings together the narratives of three intrepid women — Alice Monroe, Colette Durand and Millie Lang — in which Alice has the idea and she engages Colette as the librarian. The story is spiced up with mystery and adventure, with a further reality twist that brings in Millie by weaving in a government programme for “desperate creative professionals during the Great Depression.”

The book is as much an adventure story as a tribute to the role books, art, theatre and music play in connecting people. In effect, it acknowledges the Roosevelt government’s sagacity in understanding and enabling this fundamental principle of life.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist