The sharp, icy fingers of a howling wind snatched the sheet of paper from my hand. I screamed but no sound escaped my lips. The last page of the last book on earth was gone, disappearing into the fathomless darkness of a black hole, and I stood rooted to the ground gazing at my past, my present, my future, now echoing with emptiness. All around lay scattered — nothing, not one scrap of paper, not one book on my shelves, my desk bereft of tomes piled one on top of the other, my life a lashing sea of stories lost forever…

This is every reader’s nightmare: a world without books. If I have to say this differently, I’m grateful every day to live in an age of books of every colour, taste and texture. For the briefest moment it was feared that technology would overturn the secure world of printed books. Thankfully that threat disappeared as swiftly as it appeared, without sound or fury or madness.

Indeed, both live happily together. Kindle or Apps on the phone are fine especially on journeys when you must travel light, but the paperback in the hand, your finger turning the pages and occasionally a bookmark to remember the place where you left off — that usually always wins. Few can resist the touch and feel of books. Fewer still can remain indifferent to their smell: the toasty crispiness of new books, the mellow yellow of old; books that live and show signs of age, and become ever more beloved.

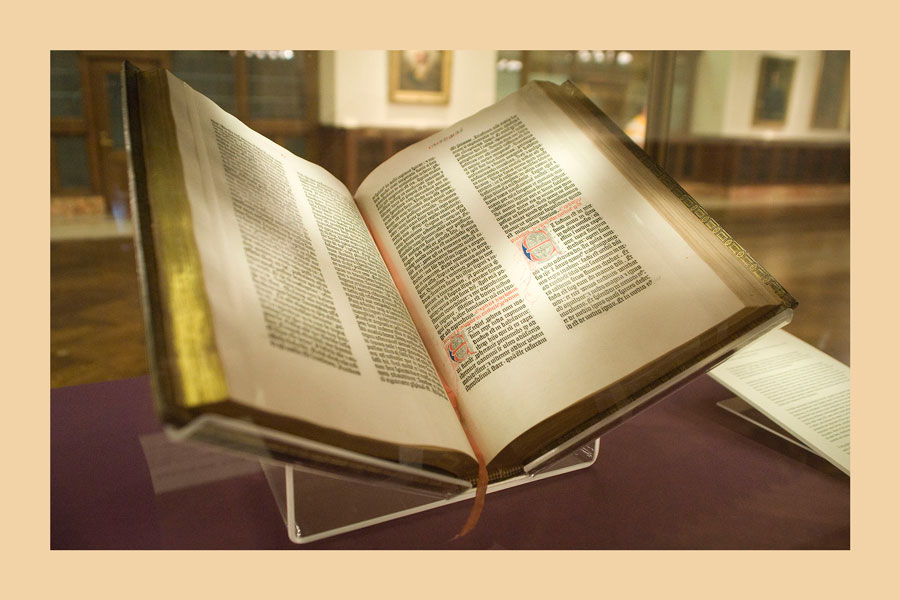

Johannes Gutenburg invented the printing press with moveable type in 1450 in Europe. This set off a book revolution that reverberated around the world. The first major book to be printed was the Bible, in Latin, popularly known as the Gutenburg Bible. However, as far back as 594, the Chinese, Japanese and Koreans were already familiar with print technology. In fact, paper was invented in China around 100 BC, and the first paper-making industry is believed to have been started in 105 AD when the Han dynasty ruled in China.

Books are babies of this collective consciousness, born after knowledge and expertise from East and West met and married. The first printed book to be born in India is said to be Tampiran Vanakkam, back in October 1578. It is a 16-page translation into Tamil of the Portuguese book, Doctrina Christam, by Francis Xavier. At the time this book was printed in India, powerful rulers of empires in Vijayanagar, Mysore, Madurai and Thanjavur were all still using copper plates and stones to disseminate information. Meanwhile the Mughal empire was consolidating itself. The Mughals knew all about books because foreigners visiting their courts often brought them along. They were not particularly interested in them, though; they were more into calligraphy. But they engaged with history and therefore every court had scribes who kept track of the emperor’s life and times. That’s how manuscripts such as the Akbarnama came to be. It is a record of Akbar’s rule meticulously documented by Abul Fazl. The Baburnama, a memoir of Akbar’s grandfather, Babur, the first Mughal ruler in India, is autobiographical. Akbar’s grandfather, unlike the grandson, was educated.

Despite the printing press, however, manuscripts continued to be handwritten: mechanical typewriters became available only in 1874. Then came electric typewriters and electronic typewriters, and today we have devices that have almost completely ended the relationship between pen/pencil and paper. Only QWERTY prevailed, then and now. Everybody knows this ‘character’: it’s the system of arrangement of letters and numerals on a typewriter. The word ‘QWERTY’ is formed by the first five letters in the row of letters just below the numerals on any keyboard, like the one on your mobile phone.

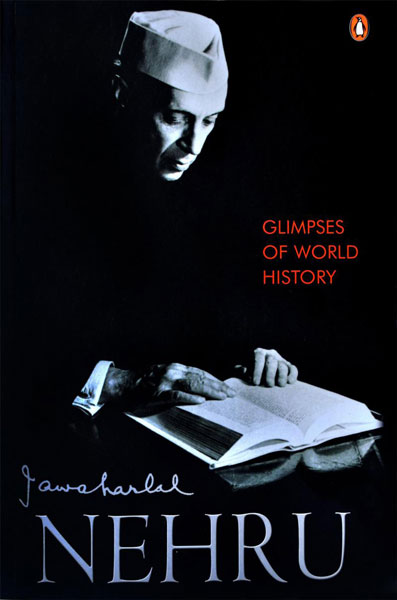

But even after the typewriter was well entrenched in society — with the Shakespeares and Tagores and others of the world scratching and rewriting their way to fame and name with inky fingers — people still wrote by hand. When I was about 11 or 12, I chanced upon a black hardbound book called Glimpses of World History. It had about a thousand pages, and was printed elegantly in small type on thin paper. The flyleaf bore an inscription that revealed that it had been gifted to my father on the occasion of his marriage on May 5, 1954. I turned the pages to the first chapter: ‘A Birthday Letter’. It said it was for ‘Indira Priyadarshini on her thirteenth birthday’, and was dated October 26, 1930, Central Prison Naini. I started reading: “On your birthday you have been in the habit of receiving presents and good wishes. Good wishes you will still have in full measure, but what present can I send you from Naini Prison? My presents cannot be very material or solid. They can only be of the air and of the mind and spirit, such as a good fairy might have bestowed on you — things that even the high walls of prison cannot stop.” I was hooked.

Described as a “rambling account of history for young people”, this book is a compilation of letters from Jawaharlal Nehru, our first Prime Minister, to his daughter, Indira. It was first published in 1934. The copy we had on our bookshelf was the fourth edition, published in 1948. It became a sort of ‘go-to’ for me. Any homework, any assignment, any time was good enough reason to randomly open the book and read whatever appeared on the pages. That’s what I’m doing at this very moment. I have flipped the book open: to pages 70–71. My eye goes to the shortest paragraph. Here’s what it says: “During the Han period two other important events are worthy of note. The art of printing from wooden blocks was invented, but it was not much used for nearly 1,000 years. Even so China was 500 years ahead of Europe.” What is this? Coincidence? Prescience? History?

I continue reading: “The second noteworthy fact was the introduction of the examination system for public officials. Boys and girls do not love examinations and I sympathise with them. But this Chinese system of appointing public officials was a remarkable thing in those days. In other countries, till recently, officials were appointed by favouritism chiefly, or out of a special class or caste. In China, any one passing the examination could be appointed. This was not an ideal system, as a person may pass an examination in the Confucian classics and yet may not be a very good public official…” Examinations — a subject the continues to vex our society!

Picture the scene: imprisoned for long periods of time even as the nation seethes and burns for freedom and the people look to you for light and direction. In that ambience, with only limited access to sources of information, you write about the world with such perspective. The details are engrossing, the writing felicitous. No, it’s not a definitive history of the world; Nehru confesses as much in the preface that there are errors and many things he probably should have rewritten or crosschecked. But as you travel with him from Carthage to France to Japan to Turkey to Russia to Germany to Arabia, you get a real sense of time and events. In a strange way, it’s comforting to understand that you too are a part of this teeming hive of activity we call earth; you belong. All this, just from letters to his teenage daughter.

And, if you are worrying about why the letter is dated October 26 when we know Indira Gandhi’s birthday is November 19, a footnote explains that in 1930 her birthday was observed on October 26, according to the Samvat era. Yes, there’s an explanation for almost everything — in books!

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist.