Integrity and objectivity appear to be deserting the media, but there is hope yet.

Some fifty years ago, an Indian politician declared, “When asked to bend, they crawled.” This is attributed to the veteran L K Advani who apparently was commenting on the media during the infamous Emergency (1975–77). That statement holds ever more relevant today, undermining the fact that the press was once considered the fourth pillar of democracy.

It is in this context that we must read Harinder Baweja’s memoir, They Will Shoot You, Madam: My Life Through Conflict. A senior journalist with wide-ranging field experience, she chronicles with an objective lens her journey through events that made a significant contribution to or dent in the contemporary history of India. Interestingly, her first big assignment (for Probe magazine) came in 1984: “Operation Blue Star had just ended, and Punjab was simmering with tension. Why had I been chosen to cover the aftermath of an operation that had serious consequences for the country? I was bewildered but I did not protest.” It doesn’t take her long to realise that the reasons, ostensibly, were that she was an army kid, she was Sikh, and she was a woman. But, as she goes on to clarify, “…I had grown up with a deep sense of being Indian. … I was a journalist, not a Sikh journalist or a woman journalist.” This commitment comes through, even if the editing could have been more mindful.

Harinder Baweja worked for several different media houses over a career than spans forty-plus years. They Will Shoot You, Madam covers some salient assignments, all of them politically significant. As mentioned, she begins with Operation Blue Star, in which she discusses the Punjab conflagration which was followed by riots after the assassination of the then prime minister Indira Gandhi. “The more violence I witnessed,” she writes, “the more I wanted to probe. There is no greater untruth than the oft-repeated line of, ‘terrorists don’t have a religion’. Spending long years through various conflict zones and societies, including Punjab, Kashmir, Pakistan and Afghanistan, I realised that religion has a lot to do with radicalisation.”

You see this play out in the different scenarios described in the book, all of which are based on information, interviews and observation. Nor does there seem cause to doubt her analysis, whether it concerns the Kashmir question, the Babri Masjid-Ram Mandir issue, the Taliban in Afghanistan, the India-Pakistan conundrum, or indeed any of the other things she talks about. She takes us into Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir after getting permission to visit it in 1994. It would appear she painted a fair picture of the situation there, else why would she would have been blacklisted and prevented from visiting on future occasions? Her ‘crime’ was the publication in India Today of an article, and an interview with Sardar Abdul Qayyum Khan, the then prime minister of POK (Azad Kashmir), parts of which are reproduced in the book. For instance, in response to her asking if trained militants were allowed to cross the LOC, he had replied: “We consider Indian-held Kashmir a part of our territory. It is no secret that militants keep coming and going. According to the UN resolutions, there is no restriction on the movement of Kashmiris from one side to another.”

In each instance, she keeps to the journalist’s creed of presenting as many sides of a story as possible. Talking about Kashmir, she shares different points of view; she also unravels a little-publicised aspect of security operations thereby introducing us to Mohammad Yusuf Parray alias Kuka Parray “who had been persuaded by intelligence agencies to become the leader of the army’s rogue army,” and chief of the Ikhwan-ul-Muslimeen which was “fighting for Kashmir’s ‘liberation’… from the pro-Pakistan Hizbul Mujahideen and the Jamaat-e-Islami.” As Harinder comments, “Instead of rehabilitating those who chose to surrender, the government decided to use them as counter-insurgents. This only added another layer to the complex web of violence in the Valley.”

Nothing is black and white, certainly not when the question is political. Written in clear, lucid prose with the additional luxury of the text being easy on the eye, the details and analysis provided in each chapter emphasise the complexity of issues underlying each of the conflicts the author reports on. They also highlight the ludicrous extent to which tit-for-tat games are carried on, and for how long. She points out that “…many of the surrendered militants felt that they were better off as ‘real militants.’ After surrendering, they had no source of livelihood and were afraid of leaving their homes. They feared they would be killed. The popular sentiment still favoured the insurgents and as (one of them) said, they were often taunted by their own extended families. ‘They ask me what I’ve earned by surrendering.’” As if this was not complicated enough, there is the rivalry between the army and the BSF: “Salim Javed, one amongst the group I met, displayed his injuries. His crime? He had surrendered to the army and not the BSF. I was shocked when one of them said, ‘The BSF officials tell us to pick up the gun once again and then surrender it to them.’ The intense rivalry was undermining the counter-insurgency operations.”

This book covers a lot of ground, right down to the Pahalgam attack that took the lives of innocent tourists, revealed the lack of security in a popular tourist spot, and highlighted the bravery of locals in rescuing as many as they did. Nor does she hesitate to call out offenders, although in measured tones. We get shocking facts regarding the impossible pressures under which Indian soldiers fought the Kargil war, all of which serve to remind us that we don’t really have all that much to celebrate. The book, in other words, is a reality check.

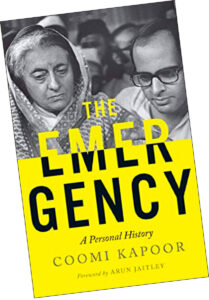

In fact, this book reminds me of a 2015 title, The Emergency, by the remarkable journalist Coomi Kapoor. It’s a personal memoir of a time when her husband, Virendra Kapoor, along with countless others, was incarcerated in prison by an insecure, vindictive leadership. Sounds familiar? But this was some fifty years ago! Still, this is a good time to remember that when a lot of the press caved, there were a few that soldiered on: “…when asked how he had continued to fight the government despite the enormous pressure on him, including crippling financial and personal consequences, Ramnath Goenka (head of the Indian Express group) replied, ‘I had two options: to listen to the dictates of my heart or my purse. I chose to listen to my heart.’” The Indian Express was one of the few newspapers to publish boldly, even as several column centimetres of reportage were redacted (blacked out) by the censors on a daily basis.

Here’s a short passage from The Emergency: “The adulation she (Indira Gandhi) received after December 1971 (when India helped liberate East Pakistan / create Bangladesh) and her sweeping victory in the subsequent Assembly elections fanned Mrs Gandhi’s megalomania. Cocooned in an atmosphere of sycophancy, Mrs Gandhi ran the party as a one-woman show. She started demolishing the democratic edifices her father had installed. She ousted powerful chief ministers without consulting the legislators and appointed lightweights in their place. Her cabinet ministers were rubber stamps to do her bidding…” These words echo eerily.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist