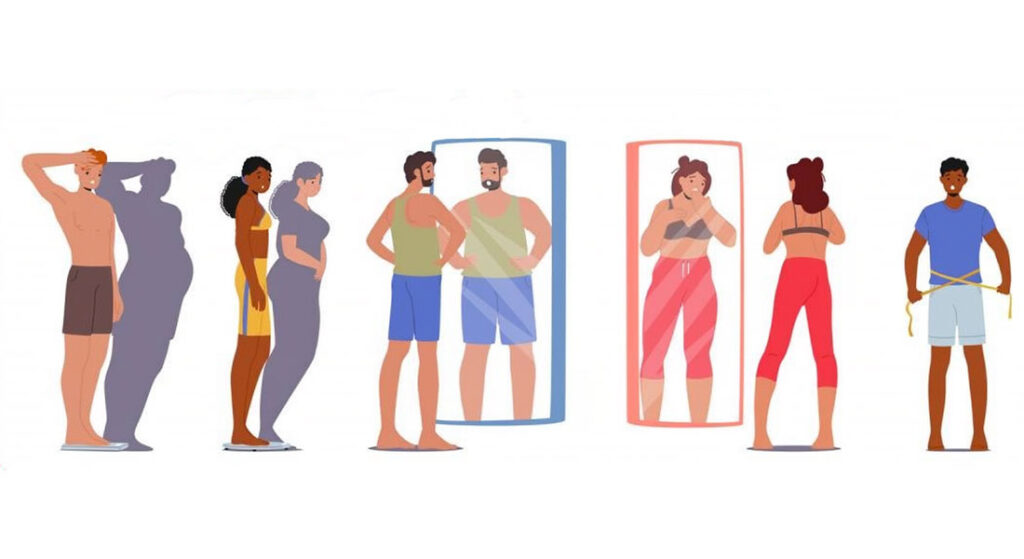

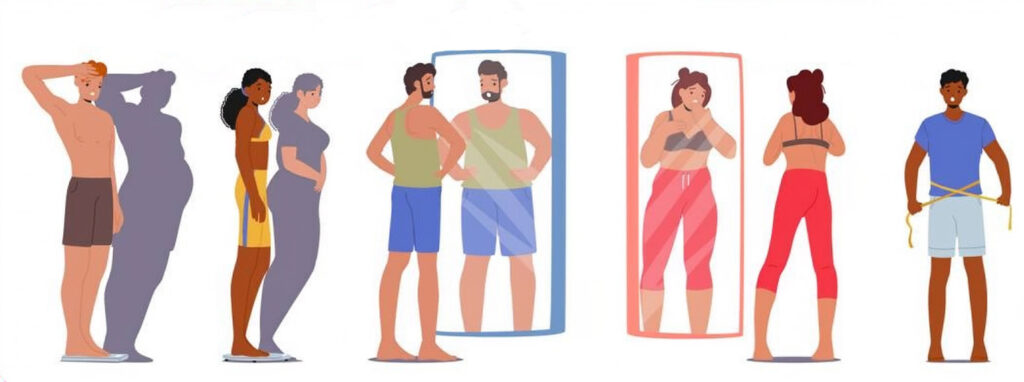

Many people are dissatisfied with their body image. They frequently tell their physicians that they are “too fat” or that their “shape is wrong.” They usually hope, with medical help or a miracle, to lose weight from specific parts of the body, such as the thighs, hips, arms, or stomach. The opposite also occurs: some individuals who are clearly overweight declare, “I’m fine,” and feel no need to diet, exercise, or modify their lifestyle.

A small minority, however, want to gain weight. Weight gain can be achieved by increasing the amount of food eaten at each meal and by adding calorie-dense snacks between meals. Exercise is still essential, but the focus is different: about 20 minutes of aerobic activity followed by 20 minutes of weight training every day helps build muscle mass in a healthy way.

“Looking good” or maintaining a desirable body weight is not merely a matter of feelings or personal opinion. It is based on scientific measurements, specifically, the Body Mass Index (BMI), calculated using a weighing scale and a measuring tape. The BMI is obtained by dividing your weight in kg by the square of your height in meters. It is a quick, simple, and inexpensive method that does not require any specialised equipment.

BMI values for adults are interpreted as follows:

BMI (kg/m²) — Weight Status

Below 18.5 — Underweight

18.5 – 24.9 — Normal

25 – 29.9 — Overweight

30 and above — Obese

Despite its usefulness, BMI has significant limitations. It does not accurately classify very muscular individuals, very thin adults, pregnant women, or people who are extremely short. Muscular people may appear “overweight” despite having low body fat, while some thin adults may appear “normal” despite having inadequate muscle mass.

For children between two and twenty years, BMI must be interpreted differently using age and sex-specific percentile charts. Any child above the 95th percentile is considered obese. Childhood obesity must be taken seriously because overweight children often grow into sedentary overweight adults with increased long-term health risks.

Body fat distribution is another important factor. Some people accumulate fat uniformly under the skin (subcutaneous fat), while others carry most of it around the abdomen. An “apple-shaped” body, with fat concentrated in the stomach area, is far more dangerous than a “pear-shaped” body, where fat is concentrated around the hips and thighs. This is because abdominal fat is often visceral fat —deposited around internal organs — and is strongly linked to diabetes, high cholesterol, hypertension, stroke and heart disease.

The waist-to-hip ratio is a simple way to assess this risk. A healthy ratio is less than 0.85 for women and less than 0.90 for men. A person may have a high BMI but still fall within the healthy range if the waist-to-hip ratio is normal, indicating lower visceral fat.

Waist circumference alone is another reliable indicator. In women, a waist circumference greater than 35 inches and in men greater than 40 inches is considered dangerous.

Even simple physical-function tests provide valuable information. One example is the “stand-up test”. The individual sits on the floor and attempts to stand up without using hands or other body parts. Each movement (sitting down and standing up) is given five marks. A healthy adult scores 8 or more regardless of age or weight. A score of 5 or less suggests poor strength, balance and overall health.

The pull-up test is another measure of fitness. Fit men can usually perform around 10 pull-ups, while fit women may manage 2. These tests assess strength, endurance and neuromuscular coordination, factors not reflected in BMI alone.

Modern research shows that all these measurements: BMI, body fat distribution, waist circumference and functional fitness tests, must be considered together to obtain a complete picture of health. Once a person falls into the “unhealthy” category, the risk of metabolic disorders such as diabetes, abnormal lipid levels, hypertension, stroke and heart disease increases sharply. Lifespan and quality of life may also be reduced.

Weight loss has become both a medical challenge and a booming commercial industry. Numerous fad diets circulate online and on store shelves. These diets often eliminate or drastically reduce essential nutrients such as carbohydrates, fats, or proteins. Many recommend replacing meals with shakes or powders, and some advertisements falsely claim that exercise is unnecessary. “Before and after” photographs are commonly used to promote unrealistic results.

Dieting alone can help reduce weight, but it does not improve fitness. Without regular exercise, the proportion of fat to muscle remains unchanged, and the health risks associated with obesity persist. Additionally, maintaining weight loss becomes difficult because restrictive or unnatural meal patterns cannot be sustained for long. Many weight-loss powders are expensive and may contain substances such as ephedrine, thyroid hormones, creatine, amino acids, hormones or even steroids.

Surgical procedures, such as reducing the stomach’s capacity, can also produce significant weight loss. However, they do not automatically improve fitness or muscle strength unless accompanied by exercise.

Even if you are reasonably fit, carrying excess body weight places additional strain on the heart, spine, hips and knee joints. It is ideal to approach both fitness and weight control together.

The simplest and most effective method to maintain long-term health is regular exercise. Walking, running, swimming, or cycling for 40 minutes daily increases cardiovascular fitness, improves mental alertness, and helps preserve muscle mass well into old age, even if you do not look particularly thin. Staying active is far more important than achieving an “ideal” size on the weighing scale.

The writer is a paediatrician and author of Staying Healthy in Modern India.