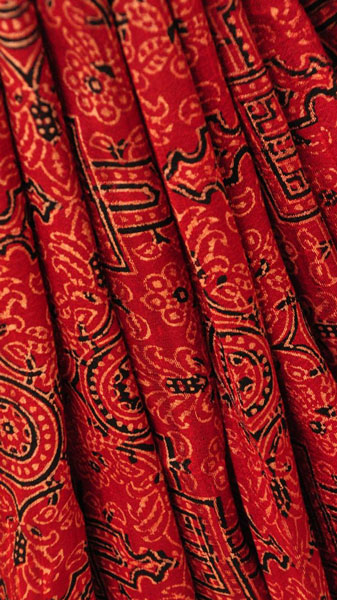

Think moonless, think midnight, think darkness or a star spangled sky, against a stark blue-black background… this is what ajrakh is likened to, with the word in Arabic meaning blue.

It is the synergy between handloom textiles and vegetable dyes which creates this magic. The introduction of chemical dyes led to the decline of natural dyes towards the end of the 19th century.

Ajrakh printing, one of the oldest techniques of resist printing in India, uses natural dyes and is one of the most complex and sophisticated methods of printing. It is also said that it could have come from aaj rakh (keep it for the day). The longer the wait between each process, the finer the result.

The ajrakh makers believe that the printed fabric has warm and cool colours which steady the body temperature. Blue is cooling and red is warm.

Legend has it that the ajrakh printers were originally Kshatriya Brahmins and decendants of Rama’s sons, Luv and Kush. The king of Kutch brought them, along with dyers, printers, potters and embroiderers, to his land which was barren and uninhabited.

The dyers were Khatri Brahmins. Two generations later they embraced Islam and settled in Dhamadka. This place was devastated by severe earthquakes twice and the artisans shifted to Ajrakpur, 12 km from Bhuj.

The ajrakh craftsmen claim that their art harks back to early medieval times. Scraps of printed fragments which were believed to originate from Western India were unearthed at Fostat near Cairo.

The finest designs were printed in Sindh which is now in Pakistan but traditions are maintained in Khavda (Kutch) and Dhamadka and Barmer in Rajasthan where few Khatri families are engaged in ajrakh printing. With almost 200 traditional geometric and floral designs, they plan to bring out a design directory.

With almost 200 traditional geometric and floral designs, the Khatri families plan to bring out a design directory.

Ajrakh printed cotton is traditionally worn by the pastoral Maldhari community. Apart from pagdis and lungis, women wear printed skirts, and use ajrakh printed material as bed covers to line cradles.

Every colour tells a story and the design proclaims the status. The Khatris have developed a contemporary market for ajrakh yardage and the print is used in kurtas, skirts, furnishings, scarves and more.

The process

A remarkable feature of ajrakh printing is that on a single fabric, using the same design, ‘resist printing’ is combined with other printing and dyeing techniques. The whole process is repeated on both sides of the fabric in perfect cohesion, which calls for unsurpassed skill.

Ajrakh uses mud-resist in the various stages and another unique feature is that the dyeing and printing is repeated twice on the fabric to ensure brilliance of colour. Superimposing the repeats is done so perfectly that the clarity is sharpened.

An ajrakh fabric can be identified by its red or blue background. Other vegetable dyes like yellow and green are also introduced. Traditionally, four colours — red (alizarin), blue (indigo), black (iron acetate) and white (resist) are used. The ajrakh makers believe that the printed fabric has warm and cool colours which steady the body temperature. Blue is cooling and red is warm.

An ajrakh fabric can be identified by its red or blue background. Other vegetable dyes like yellow and green are also introduced. Traditionally, four colours — red (alizarin), blue (indigo), black (iron acetate) and white (resist) are used. The ajrakh makers believe that the printed fabric has warm and cool colours which steady the body temperature. Blue is cooling and red is warm.

The printing blocks have to be finely chiselled by experts in the field. A set of three blocks create a dovetailing effect which finally results in the design.

A white cotton cloth is placed in a copper container with water and soda ash. It is then softened by steaming and washed in running water, preferably in a river.

Soap is applied to it after spreading it over a large cauldron of water. The cloth is then dipped in a mixture of oils, squeezed out and kept overnight.

The fabric is washed the next day and soaked in a mixture of powdered sakun seeds and oil and dried again, after which it acquires a dull beige colour. Specially designed blocks are used to print the fabric in gum using an outline block.

The second line of printing, which is kat printing, gives a black colour using a solution of ferrous sulphate and ground seeds. When it is dyed in alizarin (synthetic madder), it turns black. After the third printing with a resist made of natural elements, the fabric is dyed in indigo.

It is then washed and dyed in alizarin which produces the red colour in areas that were covered initially by resist. The second dyeing is in indigo to produce another shade of blue.

After this the final wash consists of successive washing in soda ash, detergent water and then in running water which results in a luminous and beautiful product.

Today, the process has been scaled down with shortcut methods resulting in the intricacies of lines being sacrificed. Inclusion of chemical dyes diffuse the quality of the colours, and scarcity of water has also interfered with the production. The natural products used now include gums, oil, clay lime, sakun seeds and molasses.

Today, the process has been scaled down with shortcut methods resulting in the intricacies of lines being sacrificed. Inclusion of chemical dyes diffuse the quality of the colours, and scarcity of water has also interfered with the production. The natural products used now include gums, oil, clay lime, sakun seeds and molasses.

The late Khatri Mohammed Siddique was instrumental in keeping the magic of ajrakh alive, and he passed on the tradition to his three sons, Ismail, Razzaq and Jabba.

After the 2001 earthqauke devastated Bhuj, the State government and other NGOs have extended significant support to the artisans so that the craft does not fade into oblivion. Today, it has a huge demand and even enjoys an international market.

Pictures by Sabita Radhakrishna