I quit my job in the summer of 2021. There were lots of factors, but one had absolutely nothing to do with my career as a journalist or the hollowing out of the newspaper industry. I just wanted to help my youngest child, Mateo, through his junior year at a Chicago public high school and his 16th year of life.

I soon realised that I had been a better journalist than a parent. And why not? I had worked harder at journalism than at parenting. I enjoyed it more, and I had made the decision, perhaps not consciously, that I would be a journalist first and a parent second. There’s no getting around that now.

In today’s journalism, if we make a mistake in a printed story, we edit the online version and drop in an editor’s note explaining how we corrected the error. Sometimes, we add a word of apology. But life is more like a printed newspaper than a digital website. There is no version of our lives where we can go in and unobtrusively fix the mistakes we have made.

But that’s not to say we can’t mend those mistakes. That just takes a lot more work — and yes, the occasional apology. That’s the thought that often visited me as I spent a year side-by- side with Mateo as he faced the rigors of adolescence and his own personal challenges.

Mateo struggles with acute learning disabilities that make academics extremely challenging. He can talk a mile a minute but freezes up over the most basic arithmetic. Other developmental issues make the social part of high school an impossible riddle.

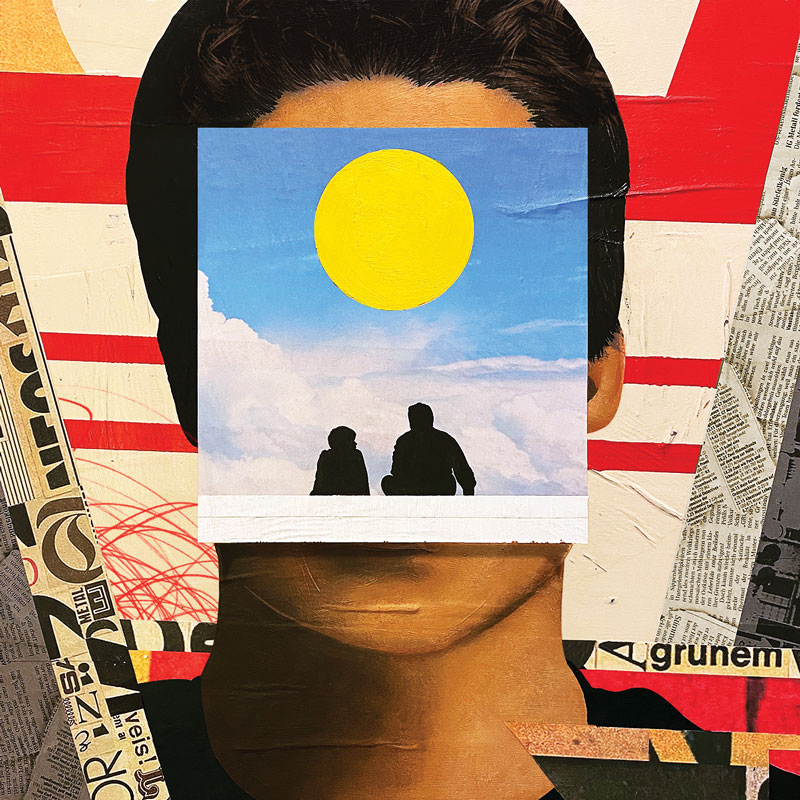

For Mateo, this was an opportunity to have his father all to himself, to indulge his harebrained hypotheticals, to reassure him in his fears.

Among the challenges is Tourette syndrome, a nervous system disorder that can cause physical and verbal tics. Adults and kids with Tourette’s might display anything from odd facial expressions to sudden and involuntary whole body movements. The vocal tics might sound like grunts or groans, squeaks, or incredibly loud hiccups.

For Mateo, Tourette’s comes and goes in waves. He enjoys days marked only by a handful of hardly noticeable events, and though peace is never quite at hand, the relative calm that descends on those days of little ticcing is like a walk in a quiet wood.

Any parent who cares for a child with chronic challenges knows that those good days bring a mix of emotions: relief, of course, and a hope, almost always false, that the worst is over. Mostly, you wonder what you’ve done right — and how long the good stretch will last.

On bad days, Mateo’s Tourette’s is a constant presence, like a taut movie score that lodges in your brain and raises your blood pressure. In the worst cases — and the most frustrating and exhausting for our beloved Mateo — he blurts out profanities, sexual terms, and even racial and ethnic epithets. It breaks your heart.

Yet for all of Mateo’s foibles, everyone roots for him. People routinely tell me that Mateo is one of the most endearing and likeable kids they have met. I tell friends that I can remember maybe two or three times that Mateo has ever woken up in a bad mood or without saying, “Good morning.” (And he’s a teenager!) Mateo simply does not have a wrong side of the bed. He is enthusiastic and curious and caring — and, so far, indomitable.

One night, after a long, hard day of dealing with being a high schooler and trying to combat his Tourette syndrome, Mateo sat alone in his room, looking at the record collection he inherited (well, gangstered) from me. He was ticcing up a storm, and his loud grunts could be heard across our split-level condominium. Asked whether he was employing the breathing techniques designed to control his Tourette’s, Mateo replied, “At least I’m not swearing.”

That’s right, kid. Let’s score this latest bout a victory.

Do bad stars align? They can, right? Because as my job as a journalist was ending, Mateo was sinking deeper into crisis.

As it was for many kids during the pandemic, especially kids reliant on specially trained educators and mental health support, remote learning for Mateo was a bust. He was disengaged from the academics, but even beyond that, he was more restive and needy than usual. Therapy got interrupted, and his Tourette’s flew into overdrive. Parenting shrunk down to one simple goal: Try to keep the lid on things.

Something needed to be done. I resolved that, at the very least, I would spend the first quarter of the 2021–22 school year working with Mateo daily and directly to get him back on track. We got him into a terrific vocational training programme called Chicago Builds, which he loved. But given Mateo’s needs and vulnerabilities, he required transportation to the programme every day.

I welcomed the role of chauffeur, and those drives with Mateo turned out to be a gift. Unlike earlier efforts to combine work and parenting — fraught conference calls over car speakers, distracted peeks at instant messages at stoplights, furious emailing from clinic lobbies, parking lots, and noisy cafes — this new routine was more focused. The daily shuttle imposed a structure on our relationship; expectations became clear for both of us. Opportunities emerged to go over homework, discuss troubling issues, plan our cockamamie weekend projects. For Mateo, this was an opportunity to have his father all to himself, to indulge his harebrained hypotheticals, to reassure him in his fears. Or we could just point out cars that we would love to buy and — Mateo’s favorite pastime — talk about whatever flew into our heads. We were each other’s captive audience.

A good friend of mine told me recently about a rough patch he’d had with his adolescent son. “We almost lost him,” my friend told me. “He almost left home.” Then my friend and his wife hit on a way to break through. They started taking long drives. And it was only cooped up in the car, lulled (perhaps) by the roll of the tires and the drone of the road, that the boy opened up about what was troubling him.

I thought about that story a lot as I drove Mateo back and forth. Our breakthroughs were nothing like the movies: no fervent bear hugs, no convulsive tears of joy. But my reward was greater: intermittent insights into Mateo’s heart and mind, insights that have helped me become a better father.

I’m convinced those insights would have eluded me had I not been fully present in the car. Like so many of us, I have learned to multitask more over the last few years. But I cannot “multithink” — and, I realise now, I never could. This time with Mateo taught me about the importance of truly thinking about what I am thinking about.

I took a year off work to help my son with his life. Only it was he who helped me with mine.

There were other insights. Among them, I learned that parenting is a test of patience. You must be patient with your children, of course, but patient also with the co-parents and the grandparents; patient with the caregivers and the teachers; and, particularly for those parents whose kids have special physical, mental, or emotional needs, patient with the healthcare professionals.

Oh, and patient with yourself.

After I left my job, I realised that I had been spending almost all my patience at work. I was giving my colleagues and my staff, as well as the institution and mission of journalism, the energy and patience with which I was too sparing at home. None of us has a limitless supply of patience. And I was misspending mine.

I realised as I spent more time with Mateo that so many of those lessons on how to parent that I had previously read about or studied or even trained in, those approaches that by and large did not work for me, were full of solid counsel. I had just failed to muster the patience to give them a real chance.

Again, despite all those insights, I can report no miracles here, no heartwarming movie endings. But I have been finding value in trying some of those parenting approaches that had never stuck with me before. My relationship with Mateo is much healthier, much more positive, much more supportive, in both directions. A gift.

Mateo and I have also enjoyed a more concrete benefit to this detour in my career. He and I had always done various projects together. What I lack in handyman ability (a lot), I make up for with stubbornness. My time off from work, coupled with the skills Mateo is learning through Chicago Builds, allowed us to fix up our 2000 Honda and do some major work around our condo building: rebuilding, repainting, renewing. Combine my diligence with Mateo’s enthusiasm, and we get through most projects with only slight signs of DIY.

My frame of mind, meanwhile, has allowed me to look at these projects as journeys, with the outcome being only part of the point. Mateo has learned to slow down and be more methodical. He is getting better about not breaking things, a common struggle for kids with severe ADHD. He’s able to own whole parts of projects, start to finish.

Looking at these projects now as learning opportunities and not just items to check off a to-do list has made me reassess my results-oriented leadership style in the workplace. I realise that driving hard on efficiency, on getting things done, has been something of a weakness of mine, not the unalloyed strength I had considered it. In prioritising results, I now realise, I had closed off paths for myself and others to learning, creativity and professional development.

None of this should imply that I think everyone should (or could) quit their jobs so they can be better parents. What’s more, I did not need to quit my job to become a better parent. I’m embarrassed it took something so drastic for me to get a clue. (Insert apology here.) As I said previously, people were sharing these lessons with me before. I just wasn’t listening.

But now that I’m back to work full time, I’m determined to have these lessons inform how I operate both at home and on the job. Maybe there is a sappy Hollywood walk-off line in here after all: I took a year off work to help my son with his life. Only it was he who helped me with mine.

Or something like that. I’m still working on it — and I’ve made time for revisions now.

The former editor-in-chief of the Chicago Tribune and chief content officer of Tribune Publishing, Colin McMahon is chief operating officer at StartupNation Media Group.

©Rotary