Any Indian village is like a multiple organ thing… if you work on the liver, the heart will, fail, if you work on the heart, the lung will fail. The life of the farmer who lives in that village is unpredictable. If I was a farmer, I would have got 10 heart attacks till now.”

With these words, Mayank Gandhi, a social activist, who had brought a revolution of prosperity in the Parli region of Marathwada in Maharashtra, infamous for droughts and farmer suicides, mesmerised a large group of Rotarians and others attending a webinar titled ‘Shifting Paradigm: Agriculture, a great opportunity’, organised by RI District 3141 PDG Rahul Timbadia’s LaTim group.

Gandhi added that farmers face such a plethora of problems and challenges “that we, the town people, can’t even imagine.” These challenges are from the weather… too much rain or lack of it, insects attacking their crops, problems with the soil, and so on.

Let’s cut to the beginning of this social activist’s foray into agriculture and organising farmers, which has enabled many Parli farmers’ income jumping up from ₹10,000–15,000 a month from 1–3 acres of land to ₹2–4 lakh, and sometimes even ₹6 lakh, from a bumper crop. Gandhi, who describes himself as “a madman who wants to change the country”, first worked with Anna Hazare, was a core committee member of the India Against Corruption movement and a national executive member of the Aam Aadmi Party.

In 2015 AAP won the Delhi elections with a thumping majority but slowly Gandhi realised that he was not suitable for the compromises and the internal fights that are inevitable in electoral politics, and quit politics.

It was the summer of 2016, “and I still had the passion to change the country, but realised that I can’t change the whole country as I have no structure, no political party.” He always kept in mind Gandhiji’s words that the soul of India lives in its villages. “But there was so much poverty and pain in villages, and the villagers’ backbone was broken. The question that troubled him was that if the village and the villagers are not successful and strong, how will the country become so.”

He admits that wanting to change a country with 6.4 lakh villages was “total madness, so I thought let me take an area where maximum farmer suicides are reported. This was Marathwada in Maharashtra, with Beed district being the worst for farm distress… it is called Maharasthra’s Bihar.”

Again, in Beed, the worst hit area vis-à-vis farmer suicides was Parli taluk with 106 villages. “I also thought that against India’s irrigated area of 40 per cent, Parli’s area was only 1.72 per cent.” So he picked up the gauntlet. But the first block was his being a “management consultant, who normally thinks he knows everything and just needs to change a little here and there. But I needed to go to a village to realise I don’t know anything, including Marathi, and first have to unlearn.”

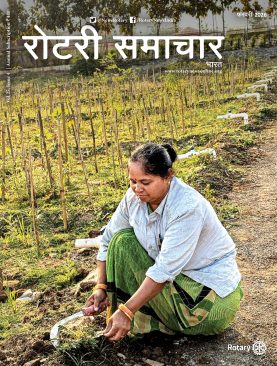

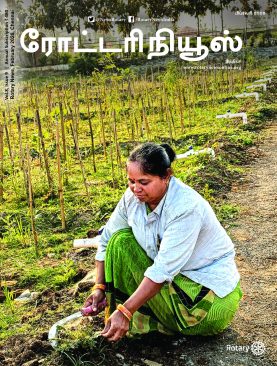

Thanks to water augmentation, the barren land started becoming green, water came, trees flourished and became a source of income and people got hope.

– Mayank Gandhi

It took him two years to get a grip over the way the economy of a village and farming works. “I didn’t know a village apart from the one I had seen in the film Lagaan!” The area used to get water through tankers, and he found here youngsters who hadn’t even tasted milk, and the monthly income of most villagers was ₹3,500. “I found that people were living because they had not died. That’s all.”

Realising that if you want to change a village, you require a 360 degree turnaround, Gandhi started, along with the local community by taking the bull by its horns. But first the villagers had to be convinced “why this man has come here from 530km away. He wants neither notes or votes, so why is he here was the suspicion. So first I had to convince them that I was a madman.”

A movement was required to transform Parli taluk, the way farming was done there and increase multifold the farmers’ income. But it couldn’t be a negative, confrontationist or destructive movement… and it couldn’t be like going to demolish a building without having a plan for the new building.

Thus was born his organisation Global Parli, and he started work in 15 villages. Gandhi explains that in the previous eight years, Parli had seen five famines. “Our first challenge was to provide water to these drought-hit villages and bring them back to their feet.”

When the drought situation in Marathwada hit the worst patch in 40 years with stored water going below eight per cent, and people faced a fourth consecutive drought, “we ended up supplying over one crore litres of water to the thirsty villagers of Beed.” After supplying water through tankers, the focus turned towards water utilisation and conservation, which was the primary and main challenge. A detailed survey of the Paapnaashi River was conducted and through persistent efforts, labour and money, “we created 70km of the Paapnaashi river… perhaps that washed away my sins,” chuckles Gandhi. Along with that, 162 ponds and five big dams were created and as a result of these water conservation and augmentation, “the barren land started becoming green, water came, trees flourished and became a source of income and people got hope.”

Earlier they had no hope but water gave them hope and they felt we can do something. It became a people’s army, corrupt leadership at the gram panchayat level was replaced by young and women leaders. Earlier the villagers had to go down 300–500 ft to get water; but now got water at 50–70 ft.

Gandhi hastens to explain that there was neither donation nor charity. “We got money from the farmers and villagers who gave ₹13.5 lakh, the remaining came from government and friends. The message was clear. We are not giving charity but just lending a shoulder.”

Soon his support base swelled to an army of people with the mantra ‘Let’s change lives’. “People started returning from Mumbai and Pune where they had gone as labourers. They said that if we can get such a beautiful life in a clean and green village why live a gutter- like life in Mumbai’s slums.”

“In 2018 there was a big famine. And we were all depressed and thought we’d have to get tankers once again for drinking water, which is like applying band aid for the red spots caused by cancer.” But the tremendous amount of water augmentation work that had been done saw them through this crisis.

A management expert thinks he knows everything, but I needed to go to a village to realise I don’t know anything, including Marathi, and first have to unlearn.

– Mayank Gandhi

But even though water gives life “the challenge is to go beyond that and increase income; you just can’t drink water and live.” Next, he and his group set about the task of growing the agro economy by forging partnerships with the agro industry, universities and KVKs (Kisan Vikas Kendra), and MoUs were signed, and a technical team was made.

After soil testing, studying weather patterns etc, the fruit trees to be planted were chosen, the entire capital expenditure, initial investment plan and other details were worked out. His team would take projectors to villages night after night and talk to farmers about profit and loss, and told them they would have to undergo at least six training sessions, all related to profitable farming, before being given quality saplings.

In the first year 12 lakh mango, sitafal, papaya, mosambi (sweet lime), drumstick and banana saplings were planted, depending on the condition of the soil, weather patterns and the farmer’s preference. Typically, each farmer was getting an income of ₹15,000 a month from the cotton and soya they had been planting, which was negligible. “Planting fruit trees is not rocket science but we did a gap analysis and found three gaps.” The first gap was quality saplings. “Just like you look at pedigree when you buy a horse or a dog, plants too have pedigree and the mother plant should be of good health and great quality,” says Gandhi.

Meticulously, nurseries which could give the best quality saplings from all over India were identified. Next the cropping patterns were changed and intensive training given. While a farmer doesn’t need lessons on how to grow a tree, he does on forward linkage, processing, value addition and marketing.

Till now, in Parli only two varieties — the drumstick and papaya have started yielding fruit. The quality of the papaya fruit is such that while last year these farmers were getting ₹10–15 per kg, now they get ₹22–28 a kg. “Some farmers who were getting ₹10,000 per acre, are now getting an income of ₹5 lakh; that is a 50-fold increase. “When such farmers started strutting around proudly, and bought a two-wheeler, others got converted.”

Rtn Sandeep Ohri, who moderated the webinar, showed two videos of farmers who vouched for their “acche din”. Said Sandeep Gitte, a farmer, “in one acre, I have planted 900 papaya trees and per acre, I get 40 to 50 tonnes of fruit, and my income has gone up from the earlier ₹20,000, to ₹3–4 lakh after expenses for papaya. Through intercropping and under the papaya trees, I have planted watermelon, and from one acre, after expenses, I get an income of around ₹1.25 lakh. Earlier I was planting cotton, and I didn’t ever dream that I could ever make so much money through farming. Now from a tin roof house I have moved into a concrete house… mere liye toh acche din aa gaye!”

Another farmer, Mukteshwar, said earlier he had to go down 400–500 ft for water, “but now we get water at 50–70 ft and are very happy”.

Let’s switch over here to the passion that PDG Rahul Timbadia has for agriculture, particularly community farming, the primary reason for his organising this webinar, to tell Rotarians and other affluent urban people that even though they may be passionate about farming, if they live away from their land/farm, they can make a profitable venture of it only through community farming.

Earlier I planted cotton, and didn’t ever dream that I could make so much money through farming. From a tin roof house I have moved to a concrete house… mere liye toh acche din aa gaye!

– Sandeep Gitte, a Parli farmer

When asked by moderator Lohri how a science and law graduate like him became passionate about farming, Timbadia said that he was always interested in agriculture. In1987 he first bought some agricultural land. He would visit Israel and Japan and in Japan “when I saw the packaged food products and their macadamia nut facilities, I realised that there is a good future in agriculture and agri-tourism.” Thus began his experiments in agriculture.

In 1991 he entered the hotel industry and “today we have three hotels, five restaurants and some agricultural activities, “where I didn’t meet with much success, but even today I firmly believe there is a huge potential in agriculture and agri-tourism.”

Later he went to Israel and studied drip irrigation and planted tomatoes and bhindi. He grew tomatoes through the hydroponics system (a type of horticulture where plants are grown without soil, by using mineral nutrient solutions in an aqueous solvent) and got a fantastic crop. But the price of tomato in 1989–90 was ₹3 a kg, “so it wasn’t really viable.”

You can easily grow 100 kg of bhindi. But then what do you do with it, you can’t eat 100 kg, and how much can you give to friends.

– PDG Rahul Timbadia

Next he went to Mehsana, studied eucalyptus farming, and planted papaya, teak and cashew trees. This was in 2005. “I got a great papaya crop, but the 2005 rains flooded my farm for five days and all the papaya trees died. I was very dejected and thought agriculture is not for me.” But in 2019–20, the cashews and teak trees he had planted, gave results. The teak trees grew to 35–40 ft and the cashew had started yielding good crop. One cashew tree gives him 32 kg with skin. But he is stuck in processing and sales network.

Giving another example, Timbadia said bhindi (okra) grows so well that if you have the space you can easily get 100kg of bhindi. “But then what do you do with it, you can’t eat 100kg, even if you want to give it to friends, you have to drive to their homes and distribute it and how many times can you give it? After a while friends will get tired and say this guy keeps giving bhindi all the time!”

While the frustrated Timbadia was in this dilemma, “a friend told me about Mayank Gandhi, and that he has helped farmers in Beed district to get ₹4–6 lakh per acre. Frankly, I couldn’t believe it, so I went there and saw for myself farmers with such happy faces, growing drumstick, papaya, banana and so many other fruits. Finally, I was convinced that there is money in agriculture.”

People started returning from Mumbai and Pune, saying that if we can get such a beautiful life in a clean and green village, why live a gutter-like life in Mumbai’s slums!

– Mayank Gandhi

Timbadia says that from 1997 he has seen that there is money in tourism industry from personal experience, and now he feels that if agri-tourism can be promoted, our farmers can benefit too.

Later, speaking to Rotary News, Timbadia described what Global Parli has done in Beed is akin to community farming. “Gandhi brought farmers together and gave them success, similarly, if untapped resources of affluent people in urban areas are diverted to rural areas, especially in agriculture, thousands of acres of barren land can be converted into orchards with fruit-laden trees, and lakhs of poor people, both tribal and non-tribal, can lead a happy and thriving life.”

Adds Timbadia, “If we pursue permaculture (development of sustainable and self-sufficient agricultural ecosystems) in huge way across the country, this could be one of the permanent solutions to combat farm distress and lift people out of poverty. Mayank Gandhi has already proved it in Beed and that can act as a beacon of hopes for millions.

He has touched a magic lamp and an organisation like Rotary, having an extraordinary network and people with great focus and motivational skills, can bring in the cascading effect throughout our country.

More details at www.globalparli.org.

Picture courtesy: Global Parli

Community farming can work for urban people

At the webinar, responding to keen inquires from people living in cities possessing agricultural land in their native places and wanting to pursue farming, or buy some land and venture into agriculture, Timbadia had a simple message — absentee farming doesn’t work for individuals. First of all, buying land with clear title was difficult and then there were problems of getting electricity, water supply, and agri expertise which is not viable for a one or two-acre plot. “So I feel the way forward is community farming; 100–200 people getting together, buying 200 acres, forming a society, and getting in place a management committee that can take decisions on what trees to plant and other issues because in farming too, as in corporates, professional management is required.” Once the produce is significant, big companies would come and buy directly.

Intervening, Mayank Gandhi said that when the landholding is small — the average size of a farm in Parli is three acres, it important to have a system which allows sharing of resources such as a tractor, technical expertise, raw materials etc. He was afraid that the recent farm bills would adversely affect the small farmers, “because the big food factories and dealers would like to deal with a larger body and not individual small farmers. The government says make FPOs (farmer producer organisation); call them FPOs or co-operatives, the future is for community farming. That is why Timbadia’s endeavour to organise interested people into a kind of collective is praiseworthy.”

Answering a question on giving guidelines to people who have idle vacant agricultural land in their native villages, Timbadia said if these people live in cities and don’t have a well-organised network to take care of their farms, “it won’t work, because plants and trees are living things and they need to be looked after. People who want to do farming and yet continue with city life… can’t do both on their own.” The advantage of living in India was that there was enough agri knowledge and expertise from agricultural universities, but it had to be sourced collectively to be affordable.

Land parcels were available, “and you can get land cheap, unlike Gujarat or Punjab, in Maharashtra, 100–150km from Mumbai at ₹12–15 lakh an acre.” If a group of like-minded people can jointly invest some ₹50 crore or so, and do community farming, they would have the advantage of hiring the best brains in India for technical. “But if you want to do farming individually on a plot of land 500km away and get results, it won’t happen. You can plant mango trees, lekin aam nahi ayenge, sirf ped hi reh jayengey (you won’t get mangoes only the trees will remain). In short, community farming is good for you, the local people and the nation.”