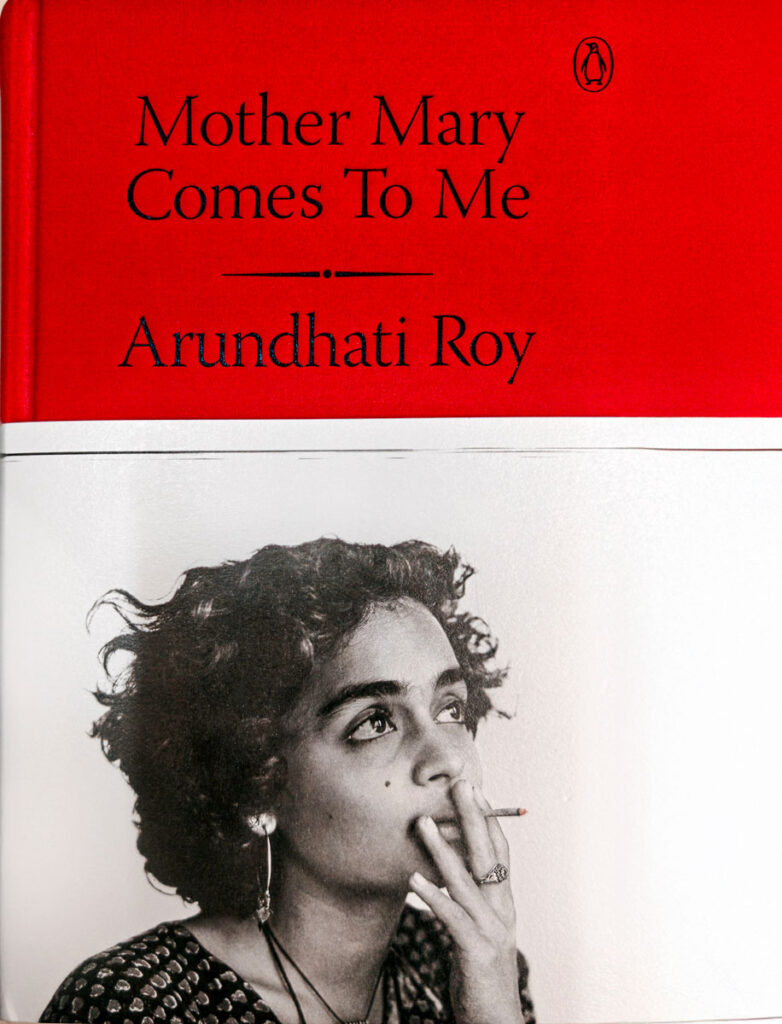

If you are not into reading and can read only one book every few months, or a whole year, it has got to be Arundhati Roy’s memoir titled Mother Mary comes to me. It reads like a thriller… packed with anecdotes, dramatic moments… searingly honest narration of feelings, emotions, relationships, the rabid, hate-filled exchanges between mother and daughter. Mother Mary is of course her mother Mary Roy, who famously waged, and won, a long legal battle for equal inheritance rights for Christian women in Kerala, because she was thrown out of her ancestral home by her brother and mother.

All of us are familiar with her powerful, hard-hitting writing… her beautiful prose, the international fame she got when her book The God of Small Things won the Booker Prize, and her essays against India’s nuclear blasts during the Vajpayee regime, in favour of the Narmada Bachao Andolan and her famous foray into a Naxal infested region.

Though this book is about her life’s journey, relationships, writing, etc, essentially the central theme is her love-hate relationship with her mother, who she and her brother were allowed to address only as Mrs Roy, as did generations of students who passed through her mother’s famous school in Kottayam, Kerala. She sums it up in the line, “In these pages, my mother, my gangster, shall live. She was my shelter and my storm.”

A feminist to the core, Arundhati writes about how in a small town like Kottayam, where there was little entertainment, as a young girl she frequently watched Malayalam and Tamil movies and grew up on a diet of women-centred narratives, “mortal or divine, who only valorized absolute submission to the python-coils of tradition and convention.” Those who transgressed faced terrible punishment and lifelong disgrace. Many Malayalam films featured a gruesome depiction of women getting raped, so and so that “as a young girl growing up on a diet of these films, I used to believe that all women were raped, it was just a matter of when and where. That accounted for the knife in my bag when I arrived at the Nizamuddin Station in Delhi at the age of 16.”

In these pages, my mother, my gangster, shall live. She was my shelter and my storm.

In this background, as the school set up by Mary Roy in Kottayam grew popular, for her girl students, “Mrs Roy was the hope for escape. She was the burning flame of courage and defiance. She lit their path, showed the way. Not so for me. My escape route always circled back to what I was trying to escape from. When it came to me, Mrs Roy taught me how to think, then raged against my thoughts. She taught me to be free and raged against my freedom. She taught me to write and resented the author I became.”

And yet, when she won the Booker Prize, the only person she called was her mother, who was awake at 2am and watching the news. Her response: “Well done, baby girl.” This, says Arundhati, was “an incredible expression of love. I’d caught her on a good day.”

Mary Roy comes alive as a larger-than-life figure and a fiery champion of women’s rights in the pages. With the help of a Christian missionary, she started a school in Kottayam in 1967 in two rented halls — which, believe it or not, belonged to the Rotary Club of Kottayam. It began with seven students including Arundhati and her brother; each morning, they would have to “sweep up the cigarette butts and clear away dirty cups and glasses left by the club members. All men, of course. To whom it would never occur to clean or clear away anything.” (Those of you female readers, who are chuckling away, can expect many such delightful home truths about the other sex!)

This school, where Mary Roy became the “owner, headmistress and wild spirit of a unique school in a unique town” would go on to become an institution to reckon with in Kottayam. Arundhati tells us that Mrs Roy was a unique woman; “she loved herself. Everything about herself. I loved that about her.” She did much more than win equal inheritance rights for Christian women. When she passed away in 2022, and her funeral had to be planned, the daughter knew that “the church didn’t want her and she didn’t want the church. (There was a savage history here, nothing to do with God)!”

The media covered her death widely and “the Internet lit up with an outpouring of love from generations of students who had studied in the school she found, whose lives she had transformed, and from others who knew of the legendary legal battle she had waged and won for equal inheritance rights for Christian women in Kerala.”

One interesting passage relates to how this remarkable woman had “disabused boys of their seemingly God-given sense of entitlement,” and describes a hilarious instance of how she dealt with boys who teased the girl students about bras!

The boys who went through her school were “turned into considerate, respectful men, the kind the town had rarely seen. In a way, she liberated them, too… she raised generations of sweet men and sent them out into the world. For the girl students, the spirit she instilled in them, was nothing short of revolutionary. She gave them spines, she gave them wings, she set them free. She bequeathed her unwavering attention and her stern love on them, and they shone back at her.”

But that revolution came at a cost, she directed all her fury against men — father, husband, brother and her own son. Once she beat him up mercilessly for getting a report card from his boarding school, saying she wouldn’t accept a son whose report card said “average student”. The daughter was “hugged for being a brilliant student”. Since that day, writes Arundhati, all personal achievements have come to her “with a sense of foreboding. On the occasions when I am toasted or applauded, I always feel that someone else, someone quiet, is being beaten in the other room.”

When the writer was devastated by her mother’s passing away at 89, “wrecked and heart-smashed,” she herself was puzzled and more than a little ashamed by the intensity of her response, leading her brother to wonder why, “because she treated nobody as badly as she treated you.” Perhaps this was true, but she had put that behind her a long time ago because “I have seen and written about such sorrow, such systemic deprivations, such unmitigated wickedness, such diverse iterations of hell, that I can only count myself among the most fortunate.”

Arundhati says that thanks to the acrimony between mother and daughter and the hateful insults hurled at her, she left home, and stopped visiting home, and returned home only at 18 when she entered her third year in the School of Architecture in Delhi.

It is the irreverence in her writing, and little pretence, apart from of course the sheer brilliant writing style, that makes this book so gripping. She calls her father, who was called a “nothing man” by her mother, who walked out on him with her two young kids, a “beloved rogue,” but indulges him by giving him money to hit the bottle. The liquor with huge amounts of varnish he consumed had “burnt his intestines and turned them to lace.”

She calls her mother all kinds of names, including Madam Houdini, but is devastated when she is put on a ventilator for three days in a Kochi hospital. Mary Roy always had lung/breathing problems, but “to watch her, this powerful woman, our crazy, unpredictable, magical, free, fierce Mrs Roy reduced to abject helplessness, was its own form of suffering.” But she fought back and lived for another 15 years, and “until the day she died, she never stopped learning, never stagnated, never feared change, never lost her curiosity.”

Arundhati doesn’t spare herself either in this book, and her searingly honest descriptions of her thoughts, feelings, emotions and relationships make this one of the most honest books. Along with words such as ‘bitch’ her mother constantly conveyed to her that her relatives often called her ‘mistress’ or ‘keep’, leading the protagonist to give herself the endearing title: The Hooker that won the Booker.

There is an interesting account of the stupendous success of her book The God of Small Things that went on to win the Booker. Once she had completed the manuscript and wanted to publish it, there was a virtual storm. Forty publishers lined up and the advance against royalties was a “ludicrous” $1 million. She felt as though she “had ambushed the pipeline that circulates the world’s wealth between the world’s wealthy and it was spewing money at me. There were all kinds of reviews. People hated it, loved it, mocked it, wept, laughed. The book flew off the shelves.”

But the book, and the buzz around it increased the complications between her and Mrs Roy a “thousandfold”. When a local fruit seller had the “temerity to ask her if she was Arundhati Roy’s mother, I felt as though she had slapped me,” fumed the mother!

The launch of the book in Kottayam met with a lot of drama, as it had offended the Communists, moral police and some conservative Syrian Christians too. She was accused of “obscenity and corrupting public morality,” and the case went on and on before finally being dismissed after 10 long years.

The oddities of Mary Roy are brilliantly brought out in this memoir. She would give her son and daughter shopping lists for the most unlikely things, mostly shoes and clothes and when she got them, she would put them on and flaunt them all at once. On one occasion, “I found her perched on the edge of her bed, looking thrilled, swinging her legs like a schoolgirl, wearing her oxygen nasal cannula, her diamond earrings, a size-44DD lilac lace bra, adult diapers and a pair of high-top Nike basketball shoes —‘for stability,’” she explained.

An entertaining passage is about the daughter shopping for her mother’s bra in a shop in Italy, accompanied by her favourite writer-friend John Berger. “Every time we entered a shop, I hung back to experience the sheer delight of watching this extremely handsome 80-something man say in his British-accented Italian, ‘Excuse me, could you show us what you have in size 44DD?’ I loved that he was helping me to buy my mother’s lingerie. I occasionally allowed myself these weird, secret games.”

One of her students wrote a book on her titled Brick by Brick, which “she edited herself, slashing through whole pages mercilessly, excising paragraphs that even briefly praised other people, rewriting sentences, as if it were a holiday assignment that her student (in his mid-50s) was turning in. Her one-page intro to her own biography, which she had signed below, as though she was signing a cheque, was entirely in capital letters,” says the writer!

Read this book for its engaging and gripping style, elegant and yet forceful prose, searing honesty, wit and humour… you will want to keep it on your bookshelves as a proud trophy.