While we lament the demise of the sporting spirit, let us pace along with two mind-bending books for willing souls.

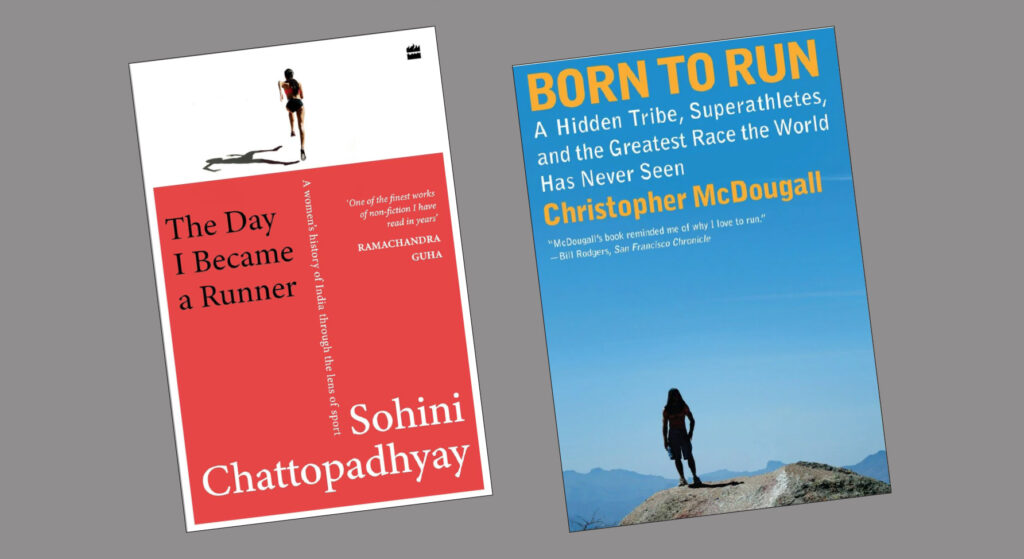

I don’t know if I would have picked up The Day I Became a Runner by Sohini Chattopadhyay if it had not been highly recommended on a friend’s book club WhatsApp group. Its red, white and black cover is a stunning example of taste and balance. Designed by Saurav Das, the highlight is all text — title, name of author, endorsement of the book, and tagline that reads: “A women’s history of India through the lens of sport”. And then you notice a tiny image of the back of a sprinter, her shadow stretching long on the background: Wow!

Comprising chapters on athletes, women who ran short, middle and long distances, as well as an organisation that trains girls to run, the book opens with an introduction curiously titled ‘The Bengali Woman’s Running Diary’. It is an introspective look at the author’s own engagement with running, which began, she says, as a mourning ritual upon the death of her grandmother. As she writes, so eloquently, ‘I was a lump in those days — a squat, easily breathless lump. I ran in the lower, unlevelled half of the garden. I didn’t deserve to run on the jogging track — I wanted to be unseen. Some of this was the grief. I didn’t want to be.’

I was reminded of an anecdote in Sheela Dhar’s delightful memoir of music and of being a diplomat’s wife, Raga ‘n’ Josh, in which she talks about the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi requesting bureaucrats’ spouses to entertain a royal visitor, the Queen of Samoa. When one of the women asked the sweet-faced, sanguine Queen what she did to keep herself busy in her country, she replied, ‘I be-s’. Such a wonderfully philosophical response when you think about it: to just be.

And in this state of just being, we turn to Born to Run by Christopher McDougall where we meet coach Dr Joe Vigil whom the author describes as “the greatest distance running mind America has ever seen”. “His head,” he goes on to write, “was a Library of Congress of running lore, much of it vanished from every place on the planet except his memory.” In the course of researching what made distance runners/running special — especially those intrepid souls not intimidated by ultramarathons that course across miles and miles of challenging terrain — he had zoned in on one aspect in particular: love. The love of running. Born to Run takes a deep dive into the world of the Tarahumara people of the Sierra Madre mountains in Mexico who — men and women of all ages — go for hundreds of miles with a smile on their lips, enjoying every moment and only very rarely sustaining injuries. Extraordinary, considering how many athletes’ careers have been cut short by injuries. What is special about the Tarahumara, McDougall writes, is that they “remembered that running was mankind’s first fine art, our original act of inspired creation. Way before we were scratching pictures on caves or beating rhythms on hollow trees, we were perfecting the art of combining our breath and mind and muscles into fluid self-propulsion over wild terrain. … We were born to run; we were born because we run.” He calls attention to the way children, when they first learn to walk, then run, just run and run; they run so they are!

We were born to run; we were born because we run. He calls attention to the way children, when they first learn to walk, then run, just run and run!

Sohini seems to echo these sentiments in her chapter on P T Usha — she can never be ignored when we speak about Indian athletes — as she describes the golden girl during the Los Angeles Olympics in 1984: “She was feeling very light on her feet those days, moving and landing in rhythm with her breathing. As if her legs were moving instinctively to the quiet music of drawing breath and releasing it. Even her heartbeat, echoing in her ears, was in sync with that rhythm.”

Through the stories, struggles, practice and points of view of athletes as remarkable as Mary D’Souza, P T Usha, Kamaljit Sandhu, Ila Mitra, Santhi Soundarajan, Pinki Pramanik, Lalita Babar and Dutee Chand, Sohini Chattopadhyay communicates a narrative that is at once thrilling and provocative, thought-provoking and prompting self-reflection. Based on in-depth interviews, these are not always stories of glory, but they are all stories of guts, whether the individuals pitted themselves against society/societal norms, or peers, or government, or themselves and their own bodies. For most people, the controversies surrounding spectacular athletes such as Santhi Soundarajan, Pinki Pramanik and Dutee Chand provided grist for gossip for a while, and then they were forgotten. Sohini reminds us why we must remember them: for their talent, for their achievements, for their courage, even if, oftentimes, sporting officialdom in India will not or, worse, penalise them, as champions Santhi, Pinki and Dutee discovered.

Over four years as a competitor, Santhi won 12 medals at the international level and several more at the national level in the middle-distance category. At the Doha Asian Games in 2006, she won silver at 800 metres. “Two days later,” Sohini writes, “Santhi had been summoned for a medical test that took place over several hours, then put on a flight and sent back home by herself that same day. A few days later, the media broke the story that Santhi had failed a ‘gender test’. Today, it seems obvious that the nomenclature is incorrect. Gender is a matter of personal identity — a personal choice. How can anyone fail a test of personal choice?” In 2012, it was reported that Santhi was working as a labourer in a brick kiln. But she was not embarrassed doing the work her family did. It was the “termination of her sports career that had left her in shock”.

The history you will find in The Day… is not about dates and dynasties, or even really about winning and losing; it is about women who dared despite the times, trials, tribulations, and in spite of society, the media and an unsparing, if short-sighted, public gaze. It will change the way you view yourself and the world around. In the way that meeting with the Tarahamura and learning about them changed McDougall’s perceptions of sport and life and the secret to happiness. Born to Run is full of amazing nuggets and anecdotes. One, for instance, is to do with chia seeds, now so essential to a healthy diet. The Tarahumara make an energy drink with it called ishiate, which is a combination of chia seeds soaked in water and topped with sugar and lemon juice. Then there is a brief but beautiful section about Emil Zatopek, the amazing Czech Olympian who once secretly slipped his 1952 gold medal for 10,000 metres into Australian Ron Clarke’s suitcase, “because you deserved it”. And Clarke thought he was smuggling a message for Zatopek! And you get to meet ‘Shaggy’, later transformed into the mysterious Caballo Blanco or White Horse and who became a legend in the Copper Canyon where the Tarahumara live, who may have started life as Micah True (or something else!) and who was the subject of the film, Run Free!

No two books on the same subject could be more unlike each other. If Sohini’s book is a series of sprints, McDougall’s is all long-distance in approach, in style, in finish, in the feelings they evoke. But in both, breath and muscle move in step with each other.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist