A best-selling novel was caught up in a controversy regarding who has the right to tell whose story.

Let’s start with a quote from the Italian writer Umberto Eco’s Five Moral Pieces, a set of five essays originally published as Cinque Scritti Morali in 1997, and subsequently in English translation in 2001. In the last of the essays, titled ‘Migration, Tolerance and Intolerance’, he examines the difference between immigration and migration. To the former he ascribes control of the political, restrictive, encouraging, planning and accepting kind. But migration is different, he says. It’s a natural phenomenon that cannot be controlled: “Migration occurs when an entire people, little by little, moves from one territory to another… There have been great migrations from East to West, in the course of which the peoples of the Caucasus changed the culture and biological heredity of the natives. There was European migration towards the American continent… What Europe is still trying to tackle as immigration is instead migration. The Third World is knocking at our doors, and it will come in even if we are not in agreement.”

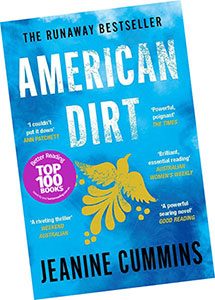

Written over 25 years ago, Eco’s exposition regarding migration, tolerance and intolerance will resonate with our times. The centre piece of this column, however, is a work of fiction, unattractively titled American Dirt. Written by Jeanine Cummins, an American whose grandmother was Puerto Rican, it focuses on the crossing over into the US of peoples from South and Central America. The world is aware of the political ramifications of this phenomenon, we are aware of the action taken by the US authorities to stop and to ferret out ‘illegal aliens,’ as they are called. But how much do we know of the whys and hows and how-longs of journeys undertaken, often over hundreds of miles, across days of danger, distress and despair? American Dirt attempts to tell one such story.

Lydia Perez runs a bookshop in her hometown of Acapulco in Mexico. The book starts off with 16 members of Lydia’s family being shot dead by members of a powerful drug cartel at the 15th birthday party of her niece, Yénifer. These include her journalist husband, Sebastian, and her mother. Lydia knows the killings were at the behest of the head of the Los Jardineros cartel; in fact, she was fooled into believing Javier Fuentes, chief of the cartel, was her friend, a fellow book-lover. But now, she and her son, Luca, are in danger for their lives, after Sebastian’s expose of the cartel.

Setting aside horror and grief, Lydia and Luca attempt to get out of Acapulco, out of Mexico, and move el norte, the north, towards and to the United States of America. The novel is an account — fictional, although based on years of research — of their journey, under cover, of many days and obstacles, including jumping onto and riding atop moving trains, crossing the desert, trusting strangers who could turn you in or shoot you down, losing all your money, and combating rattlesnakes and hunger, not to mention evading omnipresent drug and border patrols.

It’s a compelling story told at a fast pace and in great detail, although at times it does seem overwritten. However, when you get used to the style, it hooks you in for the most part. And because you know that movement along the Mexico-US border is ongoing, it is all the more compelling. As Lydia and Luca meet up with others escaping from further south than themselves, you get to know their stories as well, their reasons for leaving home. It’s not because they want to leave, they have no choice. If they must live, they must leave.

While the US is tracking down, what they call ‘illegal aliens,’ the South and Central Americans trying to cross over into the US, how much do we know of the whys, hows and how-longs of journeys undertaken, across days of danger, distress and despair?

We discussed this book at our last book club meet to mixed response. But for all of us, what was being described was unfamiliar, simply because we are in the privileged position of not being insecure at ‘home’ — at least, none of us, as of now. Generally, the simplistic view is that if you don’t find yourself in a particular situation, then it cannot be true. That is, if it isn’t happening to me, it isn’t happening to anybody. This is where S T Coleridge’s advice to suspend our disbelief willingly comes in handy. Only then can we understand, empathise, even if we have not experienced/cannot experience it ourselves.

Then again, it’s easy to get used to something, however horrible, however detrimental, over a period of time. Soledad and Rebeca, teenagers on the run from narcos who attacked their cloud-forest village in Honduras, teach Lydia and Luca how to get on and off trains. A few times of doing this and “they board easily, without even much forethought or communication.”

“We’re becoming professionals,” says Soledad. But Lydia is troubled. After reflecting on their circumstance for a bit she says, “From now on, when we board, each time we board, I will remind you to be terrified. And you remind me, too: this is not normal.” Soledad responds, “This is not normal.” They, as we, cannot allow evil things, unjust things, bad things to be normalised or they — and we — will forget to be vigilant, to respond.

Why did American Dirt whip up controversy despite being a best-seller and despite receiving such good reviews initially? There’s plenty of ‘dirt’ available online at the click of a button. However, one of the things worth mentioning that irked Latin American writers in particular was a ‘white’ woman telling ‘their’ story. Apparently at some point, in the course of an interview, Jeanne Cummins had identified herself as ‘white’ and this became a sore point. In an interview published in The Guardian in May 2025, Lucy Knight writes that Jeanne Cummins wasn’t prepared “for the string of bad reviews, one calling the book ‘trauma porn’. Whether Cummins had the right to tell the story of Mexican migrants, being neither Mexican nor a migrant herself, was called into question, and 141 writers signed a letter to Oprah Winfrey, asking her to remove it as a book club pick.”

Generally, the simplistic view is that if you don’t find yourself in a particular situation, then it cannot be true. That is, if it isn’t happening to me, it isn’t happening to anybody.

The letter noted, among other things: “In the informed opinions of many, many Mexican American and Latinx immigrant writers, American Dirt has not been imagined well nor responsibly, nor has it been effectively researched. The book is widely and strongly believed to be exploitative, oversimplified, and ill-informed, too often erring on the side of trauma fetishization and sensationalization of migration and of Mexican life and culture….”

I guess there’s plenty to be said on all sides. Ross Sempek wrote on the Intellectual Freedom Blog in March 2020 that the novel is “determinedly apolitical”. He wrote, “I believe that narratives can transcend politics, and I think that was exactly Cummins’ intention. Why add an ephemeral political stance to the timeless narrative of immigrants?” As for the question of who may tell whose story, a debate that rages on, even in the world of children’s literature, Sempek’s simple answer is: “No one should hesitate to write something because of the potential for backlash. Telling meaningful stories involves risk.” About the criticism that Cummins’ work revealed shallowness of research, he says, “I don’t know the details of Cummins’ studies but five years is enough for a master’s thesis… How is this not deep? The fact that the product of research doesn’t reflect how you would have done things is not a fair critique of the book.”

My recommendation? Read the book. Read about the book. Draw your own conclusions. But read.

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist