The English historian, Lord Acton, said in a letter to Bishop Creighton of the Church of England in 1887 in the context of writing history: ‘I cannot accept your canon that we are to judge Pope and King unlike other men, with a favourable presumption that they did no wrong. If there is any presumption it is the other way against holders of power, increasing as the power increases. Historic responsibility has to make up for the want of legal responsibility. Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely.’

Historical records reveal how absolute power makes for authoritarianism. Civilisations come and go, monarchies rule and crumble, governments exceed their remit and are ousted, leaders are ejected from groups, communities, villages, towns, cities, nations, regions for what the people perceive as wrongful actions and unfair practices. Our recent history swells with such examples that usher in change, be it the songs of the beat generation, pro-democratic efforts by the dock workers of Poland, the emergence of an Arab Spring, farmers’ protests against black laws, and, most recently, students’ ire in Bangladesh. The key lies in the hands of the people.

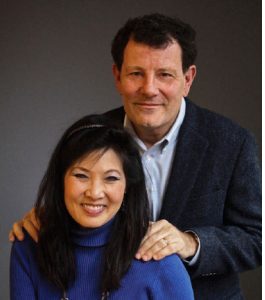

All these thoughts have come to mind as I’ve been reading a massive tome called China Wakes: The Struggle for the Soul of a Rising Power. It’s an old book, first published in 1994, by journalists Nicholas D Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn. They were the first married couple to win a Pulitzer for journalism when, in 1990, they were recognised for their reporting on the pro-democracy students’ movement and the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. The book is based on their study and understanding of China at a time it was growing to become the economic power it is today; simultaneously, it reads like a chiller-thriller as it details the rule of a totalitarian state encompassing rampant corruption, abuse of power, oppression of the voiceless, subjugation of the peasantry… . The authors have written alternate chapters, with Sheryl Wudunn, American of Chinese origin, giving her perspective an extra, personal dimension.

Reading the book also reminded me of the April 2022 Wordsworld column titled ‘Fifty Years of Bangladesh’ which featured a fiction trilogy by Tahmima Anam; a book based on the spontaneous visit to Dhaka by three students of IIM-Calcutta following the liberation of Bangladesh; and Salil Tripathi’s presciently titled The Colonel Who Would Not Repent: The Bangladesh War and Its Unquiet Legacy. To quote from it: ‘The title … refers to Lt Col Farooq Rahman who, on August 15, 1975, “led the Bengal Lancers, the army’s tank unit under his command, to disarm the Rokkhi Bahini, a paramilitary force loyal to Sheikh Mujib” and then led a team of officers and soldiers on a killing spree to finish off Sheikh Mujib and his family. Only two daughters, one of them the recently ousted prime minister Sheikh Hasina, escaped because they were abroad at the time.’ Well, once again Sheikh Hasina has fled Bangladesh and many of us have seen visuals of Bongo Bondhu Mujibur Rahman’s statue being toppled, in all likelihood due to mob frenzy. Maybe this is a good time to read this book in order to at least partially understand not just what’s happening in Bangladesh, but the region as a whole.

Expecting only to engage with interesting or curious aspects of China’s contemporary history, I launched into China Wakes with a laidback attitude. However, I quickly sat up upon encountering numerous points at which I could draw parallels with what had happened or is happening in and around our geographical ambit. It underlined in no uncertain terms that history repeats itself in the way human beings act, both as individuals and as collectives, in various contexts and combinations, with relation to power and absolute power. This seems to apply equally to both sides of the coin.

I urge you to draw your own conclusions based on a sampling of excerpts from the book.

What was behind this culture of silence in China? Why did no one protest against the regime? Most leading intellectuals publicly supported what they privately denounced… blame also must be laid at the feet of the ordinary citizens.

This passage is from page 54 (in my copy): ‘A few months before the games began, we noticed construction along the side of Stadium Road. Weeks later the construction began to take shape, and we noticed a flat cement wall, like a stage set … More weeks passed, and the wall was painted gray, with white lines to make it look as if it were made of bricks. The houses were now completely hidden, and from the street the set resembled the brick wall of a large, stately residence…’

On page 169, you read the following, about officially arranged visits: ‘…with time it became clear to us that the authorities do not just manipulate the truth. They lie. … Those who never visited China reported far more accurately than those who visited the country. Most of the critical reporting … stands up fairly well to the test of time. But travelers to China wrote gushy pieces about how happy the Chinese were with the communes, and these portraits now come across as naïve and ridiculous.’

A few pages later (175): ‘The party extracts funds from the peasants and subsidizes city dwellers, largely because of fear that disgruntled urban workers might take to the streets to protest. This is a common third world phenomenon. In Europe and North America, governments subsidise farmers and pay them not to produce, or else pay them above-market prices for corn, milk, and wheat. In developing countries like China, governments are worried about urban unrest, so they pay farmers below-market prices for their cotton, cocoa, and rice, ensuring that city dwellers can eat their fill cheaply.’

About the conspiracy of silence, read what it says on pages 244–245: ‘What was behind this culture of silence in China? Why did no one protest against the regime? … Most leading intellectuals publicly supported what they privately denounced. … a share of the blame also must be laid at the feet of the ordinary citizens … In the West, we have the luxury of being able to say publicly what we think. We scarcely understand the concept of being forced into repulsive compromises. But in China, everyone makes these compromises and the question is simply where to draw the line.’

China Wakes looks at different facets of the nation’s story, both positive and negative, thus giving the reader a logical analysis of how it has become the world’s economic frontrunner alongside its many actions that are questionable on the human rights front. The authors offer an interesting explanation for its economic successes: ‘China’s economic boom seems to have been a chemical reaction of sorts. The first ingredient was the Confucian heritage that emphasized education and savings. Then came the Maoist revolution that unified the country, broke the entrenched interests, divided up the land, and supplied financial and human capital. Third were the quasi-capitalist policies of Deng Xiaoping. None of these factors was enough by itself; in combination they have been explosive.’

Somewhere towards the end of the book, the authors write: ‘Heraclitus, the ancient Greek philosopher, said that you can never step into the same river twice. The water flows, so the river is always different. … We arrived in one China in 1988, and we left a very different China in late 1993. It was richer, healthier, and more self-confident … Jailers still torture political prisoners, but now the family members complain and sometimes hold press conferences.’

The columnist is a children’s writer and senior journalist